NOTES ON THE NOVEL: ISSUE 7

MAPS & ILLUSTRATIONS

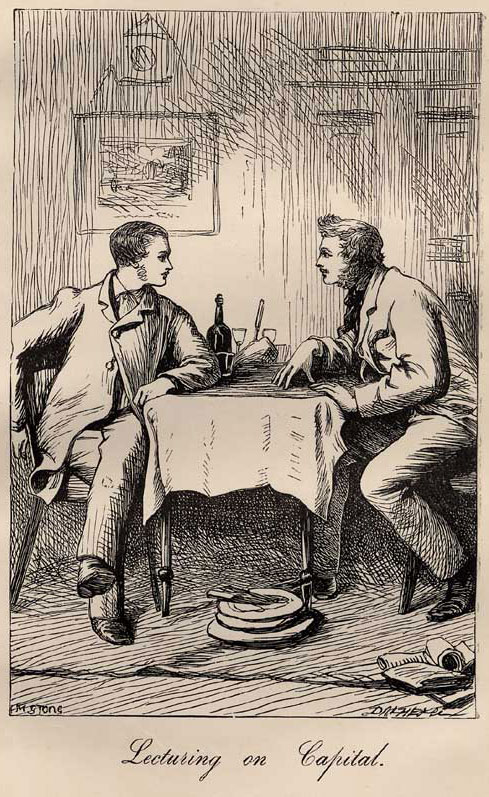

The illustration below, by Marcus Stone, appeared in the 1862 edition of Great Expectations. The original serial (1860-1) and the 1861 editions of the novel were not illustrated.

A Note on the Maps

The maps used to illustrate this issue are reproduced from Collins' Illustrated Atlas of London, published in 1854. Pip's London would have been that of the 1820s, and Dickens' London, at the time he was composing the novel, was that of 1860-1. Collins' maps thus represent a London that falls between the historical moment represented in the novel and the historical moment of the novel's composition.

Since Pip arrives in London in the summer of 1823 (Meckier 158), the maps used to illustrate this issue show a city that has undergone about 30 years of change since Pip's time. Nevertheless, they are very useful in tracking Pip's progress through the city; the reader should merely keep in mind that some of the landmarks would not have existed in 1823. The most significant of these are the railway lines marked on the Key Map -- the railroad did not enter London until the late 1830s and early 1840s (Tallis's Illustrated London 186-7). The Key Map also shows a bridge that Pip would not have recognized -- the Hungerford Bridge between Waterloo and Westminster Bridges. And London Bridge was, in Pip's time, Old London Bridge -- a different structure, but built in essentially the same place. (New London Bridge would have begun construction a few yards from Old London Bridge when Pip was living in London, but would not have replaced the old bridge during his tenure [Meckier 162]. Given that both London Bridges would have been mapped in the same place, the difference between the bridges makes no difference to our reading of the map.) Any further discrepancies will be noted where appropriate.

History and Features of Collins' Atlas (1854)

Collins' Atlas was created in response to the amplified tourist trade in London resulting from the Great Exhibition of 1851. Previous to the Atlas, maps tended to be very large and unwieldy, and though large city maps could be folded up and carried, Collins designed his maps with a specific view to portability (Dyos 10). The Atlas consists of one large map of the whole city of London (the Key Map), followed by 36 plates. The Key Map is drawn with numbered sections, and these sections are represented in detail by the plates (the numbers on the Key Map refer to the numbers of the plates). The chief drawback to the Atlas is that, although the Key Map keeps North at the top, the plates do not always observe this convention (Dyos 13). This disregard of the compass, however puzzling to someone attempting to navigate London in 1854, is in many respects an advantage for the modern reader: The detailed plates -- drawn to represent popular views of the city and/or popular routes through it -- give us a unique view of the sites of Pip's adventures in 19th century London. Any major discrepancies between the landmarks shown on the maps and those that Pip would have been acquainted with (given that the map was composed in 1854, about thirty years after Pip's tenure in London) will be indicated where appropriate.

A Note on the Illustrations

Like Collins' Atlas, the engraved illustrations of London reproduced in this and subsequent issue(s) were prepared as a result of the Great Exhibition of 1851. Tallis's Illustrated London (published in 1851-2, in two volumes) was created specifically to commemorate the Exhibition, and furnishes, not only a great many engravings of London scenes, but also a long history of, and commentary on, the sights of London. Since Tallis's Illustrated London was published, like Collins' Atlas, about 30 years after Pip's tenure in the city, some of the views commemorated in Tallis's would not have been available to Pip. Thus, only those illustrations that show cityscapes and landmarks as they would have appeared to Pip in the 1820s have been included here.

A tour of Chapters 20-22: Pip arrives in London

The Key Map in Collins' Atlas (below), showing London as a whole, gives a useful overview of Pip's progress in this issue. All of the maps reproduced here have been highlighted for convenience of reference and increased legibility.

The action in Chapters 20-22 of Great Expectations occurs mostly in the area north of the Thames River, marked on the Key Map by numeral 10 (referring to the area shown in detail on Plate 10 of Collins' Atlas), and also at locations in areas 1 and 18 (Plates 1 and 18). The areas on the Key Map corresponding to Plates 10, 1, and 18, are highlighted above.

Plate 10 of Collins' Atlas (below) shows the place where Pip alights in London, the location of Mr. Jaggers' office, the neighborhood that he explores while waiting for Mr. Jaggers, and the way to his lodgings at Barnard's Inn.

The Plate includes certain elements of 1854 London that would not yet have existed when Pip gets out of the coach in 1823 -- the Great Northern Railway Terminus (mentioned in the caption) was not yet constructed, and the General Post Office (illustrated at the bottom center of the Plate), though commenced in 1818, was not completed until 1829 (Tallis's Illustrated London, vol. 1, 206). However, the following landmarks, actually named in the narrative, are visible on the Plate:

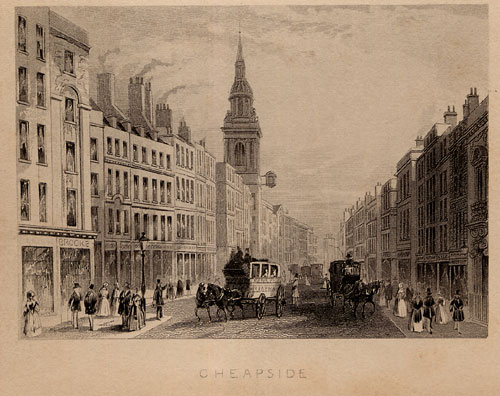

Pip alights at the Cross-Keys (an inn which served as the coach terminus from the 17th century to the 1830s [Mitchell 494]) in Wood Street, Cheapside, London (Ch. 20). Wood Street and Cheapside are visible at the lower left corner of the map above.

Tallis's Illustrated London (1851-2) furnishes us with an engraving (below) of Cheapside.

Jaggers' office is located in Little Britain, visible in the lower left corner of Plate 10 of Collins' Atlas (see Plate 10 above) above and to the right of Cheapside; he has written to Pip that it is "just out of Smithfield, and close by the coach-office" (Ch. 20). Smithfield is visible as the square marked "West Smithfield," above Little Britain. It was called "West Smithfield" to distinguish it from "East Smithfield" (which was located near the Tower of London) (Tallis's Illustrated London, vol. 1, 224).

Tallis's gives us this view (below) of Smithfield -- a cattle market. It is much in keeping with Pip's description of the place as filthy, with the "great black dome of Saint Paul's bulging" (Ch. 20) behind it.

Pip returns to the office but, finding that Jaggers has not yet returned, goes out again, this time to Bartholomew Close, which is visible -- just below and to the right of Little Britain -- on Plate 10 (see Plate 10 above) of Collins' Atlas.

Pip finds that he is to board temporarily with young Mr. Pocket, at Barnard's Inn. Wemmick conducts him up Holborn Hill, which is visible on Plate 10 (see again Plate 10 above) at the upper left, to the right of the engraving of Newgate Prison (of which Pip also gets his first sight in this issue). Barnard's Inn is also visible on the Plate, branching off Holborn Hill on the left. Tallis's describes Barnard's Inn as "possessing no architectural pretensions" (vol. 2, 11), which is apparently a tactful version of Pip's description of the Inn in Chapter 21 -- "the dingiest collection of shabby buildings ever squeezed together in a rank corner as a club for Tom-cats."

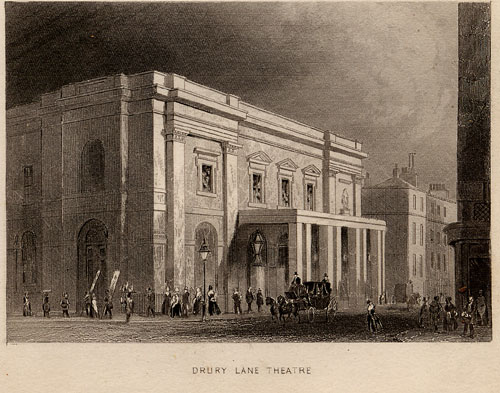

Recounting his first adventures with Herbert Pocket, Pip describes outings to the Theatre and to church at Westminster Abbey. The Theatre would have been either Drury Lane Theatre or Covent Garden Theatre (Mitchell 495). Both Drury Lane and Covent Garden Market are visible on Plate 1 of Collins' Atlas (below), in the lower portion of the Plate, toward the middle.

Drury Lane Theatre is marked on Plate 1 at the lower end of Drury Lane; Covent Garden Theatre is not marked, but would appear below and to the left of Covent Garden Market, under Russell Street. The Covent Garden Theatre faced Bow-street, which, though not marked on the map, turns into Wellington Street (which is marked), which turns into Waterloo Bridge (also marked). Westminster Abbey is visible at the top right of the Plate. As indicated previously, Hungerford Bridge, which appears on this Plate, would not have existed during Pip's time in London.

Views of both Theatres (Drury Lane and Covent Garden) are reproduced below from Tallis's Illustrated London. Covent Garden was known as the Royal Italian Opera House after 1847, and thus appears in Tallis's under that name.

Westminster Abbey (below), where Pip and Herbert go to church, is depicted in Bicknell's Illustrated London (1847).

Plate 18 of Collins' Atlas (below) shows the location of the Royal Exchange, which Pip visits in Chapter 22 ("I went upon 'Change, and I saw fluey men sitting there under the bills about shipping...").

The Exchange illustrated in the lower right corner of this Plate is not the same Exchange that Pip would have visited in 1823, because Pip's Exchange burned down in 1838 (Tallis's Illustrated London, vol. 1, 264-5). If the illustration is not perfectly accurate, however, the map is still reasonably so, as Pip's Exchange, like the Exchange marked on the Plate, was in Threadneedle Street (which extends to the Cheapside Poultry). The illustrations of the Guild Hall and the Bank of England show the buildings as they would have appeared in Pip's time, except for some repairs and additions made to the Guildhall in 1837 (Tallis's, vol. 1, 251). The railway terminals mentioned in the caption of the Plate would not have existed when Pip was in London.

ALLUSIONS

Like the Bull in Cock Robin pulling at the bell-rope: The man "pulling a lock of hair in the middle of his forehead" (Ch. 20) reminds Pip of the bull in the children's poem "Cock Robin." In this simple poem, the death of Cock Robin is announced -- "Who killed Cock Robin? / 'I said the sparrow, / With my bow and arrow, / I killed Cock Robin'" -- and a series of animals (a fly, an owl, a rook, a bull, etc.) prepare for his funeral. The bull offers to toll the funeral bell: "Who'll toll the bell? / 'I said the bull, / With my mighty pull, / I'll toll the bell.'"

The Harmonious Blacksmith: There is, as Herbert asserts, a "charming piece of music by Handel" (Ch. 22) called the "Harmonious Blacksmith": Handel's 5th harpsichord Suite in E (1720) is part of a set of eight suites. Handel did not call it "The Harmonious Blacksmith"; it acquired this nickname after his death (Oxford Dictionary of Music). Sample recordings can be found at http://www.midiworld.com/handel.htm under "Keyboard Music."

GLOSSARY OF HISTORICAL THINGS & CONDITIONS

Coffee-house: In the 17th and 18th centuries, a coffee house was "[a] house of entertainment where coffee and other refreshments [were] supplied ... [m]uch frequented ... for the purpose of political and literary conversation, circulation of news, etc." (OED, "coffee-house"). Coffee-houses in the 19th century began to lose their character as places of conversation and entertainment, but offered more substantial fare than the coffee-houses we are familiar with today.

Counting-house: Herbert Pocket is in a counting-house, meaning an office -- a "building, room, or office in a commercial establishment, in which the book-keeping, correspondence, etc., are carried on" (OED, "counting-house"). While "looking about him" for capital with which to become an Insurer of Ships, Herbert works as a clerk.

Fluey: When Pip refers to the "fluey men" at the Exchange (Ch. 22), he is describing the condition of their dress as covered with "flue" -- particles of waste matter; fluff. The Oxford English Dictionary uses Pip's reference to fluey men as an example of the historical usage of "fluey" (OED, "fluey").

Hackney-coach: Hackney-coaches were like horse-drawn versions of the modern taxi-cab. The Dictionary of Daily Wants (1858-9), gives the following account:

HACKNEY CARRIAGE. -- Under this term are included every carriage, except a stage carriage, or a carriage impelled by the power of steam, or otherwise than by animal power, with two or more wheels, which is used for the purpose of standing or plying for hire, at any place within the distance of ten miles from the General Post Office in the City of London. All hackney carriages must have four plates, namely, on the back, each side, and inside, to contain the name and address of the proprietor.... Any person desirous of obtaining a license to keep, use, or let to hire a hackney carriage, must apply in writing to the Commissioners of the Police of the Metropolis, who, if on inspection, deem the carriage fit, and in proper condition for public use, shall grant the necessary certificate. Upon the production of such certificate at the office of Inland Revenue, a license will be granted. After grant of license, police may inspect carriages and horses; and if unfit for use, license may be suspended.... (498-9)

Mourning ring: Wemmick's mourning rings are rings worn "as a memorial of a deceased person" (OED, "mourning ring"). His brooch, which represents "a lady and a weeping willow at a tomb with an urn on it" seems to fit the broader description of mourning jewelry -- jewelry "decorated with funereal ornaments or pictures." One of the quotations used by the OED as an example of the usage of "mourning jewelry" indicates that mourning jewelry "became particularly fashionable in the second half of the 18th century.... Earlier mourning jewelry of the 16th and 17th century was of a more gloomy kind" (OED, "mourning jewelry").

Pottle: A pottle is "A small wicker or 'chip' basket, especially one of a conical form used for strawberries" (OED, "pottle"). A chip basket is "a basket made of strips of thin wood roughly interwoven or joined, used chiefly for packing fruit for the market" (OED, "chip basket").

Spelling-book, moral story out of: Herbert proposes to call Pip "Handel" because Philip (Pip's actual first name) reminds him of "a moral boy out of the spelling-book, who was so lazy that he fell into a pond, or so fat that he couldn't see out of his eyes..." (Ch. 22). Spelling-books were educational primers, which, together with vocabulary and grammar, were often designed to instill moral principles in the young children reading them. Typical lessons included short paragraphs on salutary topics, with notes on the meaning and pronunciation of hard words; platitudes to be copied as aids to vocabulary and spelling; etc. The tone of passages in spelling-books tended to be stern, and the kinds of stories used to convey a moral varied. For example, Picket's Juvenile Expositor, or Sequel to the Common Spelling-Book: Containing a Collection of the Most Useful Words in the English Language, Clearly Explained, and Adapted to the Comprehension of Young Persons ... with a Course of Reading Lessons in Prose and Verse, Selected from the Best Writers (1813) contains accounts of good boys (such as a boy who breaks a looking glass but confesses and is rewarded for his honesty), bad boys (such as a boy who pulls the wings off flies), animal fables, and morally-inflected tales from history, the bible, and mythology. Sentences intended to build vocabulary are similarly inflected. For example, "To be good is to be happy [Happy, ... To be in a state of felicity] / Vice, soon or late brings misery [Misery, ... unhappiness, calamity, wretchedness]" (32). Another spelling book, The Sure Guide to the English Tongue, or New Pronouncing Spelling Book Upon the Plan of Perry's Standard English Dictionary, Now Made Use of In All the Celebrated Schools in Great Britain, Ireland and America, to Which Is Added, a Grammar of the English Language; and, a Select Number of Moral Tales and Fables for the Instruction of Youth (1801), gives lessons in a similar format, collecting the stories at the end. One of these is similar to the nursery story of "The Boy Who Cried Wolf":

The Folly of Crying upon Trifling Occasions

A little girl who used to weep bitterly for the most trifling hurt, was one day attacked by a furious dog. Her cries reached the servants of the family; but they paid little attention to what they were so much accustomed to hear. It happened, however, very fortunately, that a countryman passed by, who, with great humanity, rescued the child from the devouring teeth of the dog. (96)

Stage-coach: A stage-coach was a horse-driven vehicle running "daily or on specified days between two places for the conveyance of passengers, parcels, etc." (OED, "stage-coach"), in use especially before the spread of passenger railroads in the 1830s and '40s.