![]()

NOTES ON ISSUE 10: GLOSSARY

"after his beloved

father died, when he was eight years old, his mother, too, could pinch a bit,

as it was her duty and her pleasure and her pride to do it, to help him out

in life, and put him 'prentice."

In other words, as a young boy Bounderby was sent to work as an apprentice,

a common means of training less-well-off children to a useful trade. (Recall

that early in the novel, Bounderby and Gradgrind asked why Sissy Jupe had not

been apprenticed.) Apprenticeships were also common in some of the professions;

lawyers and doctors, for instance, underwent apprenticeships for their training.

Parents wishing to apprentice their children had to find a master for them and

sign a contract stating that the child was "articled" (bound) to the

master, who received a fee. The child then usually lived and worked with the

master for a period of at least seven years. It is not clear here what trade

Bounderby was learning.

"though his mother kept but a little village

shop, he never forgot her, but pensioned me on thirty pound a year—more than

I want, for I put by out of it"

Compare this small pension—barely more than half a pound a week—to Mrs. Sparsit's

salary of £100 per year. To live on this sum and put some money aside, Mrs.

Pegler must be extremely frugal or else must still earn some small income from

her shop.

As Coketown cast ashes not only on its own head

but on the neighbourhood's too—after the manner of those pious persons who do

penance for their own sins by putting other people into sackcloth

The image of the ashes here is taken from the Catholic custom (also practiced

among High Church members of the Church of England) of sprinkling ashes on the

heads of those who have confessed on Ash Wednesday, at the beginning of Lent.

The aside concerning putting other people into sackcloth is most likely a sly

jab at strict Sabbatarians, who sought to put a stop to all amusements on Sundays

as well as to railroad travel on Sunday.

It was customary for those who now and then thirsted

for a draught of pure air, which is not absolutely the most wicked among the

vanities of life, to get a few miles away by the railroad, and then begin their

walk

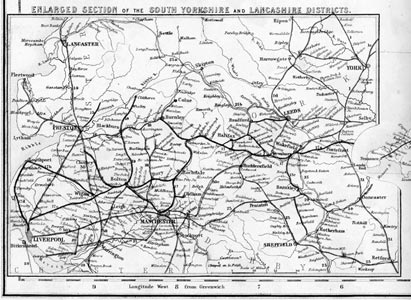

Weekend "excursion trains," which were quite inexpensive, were very

popular in the industrial areas so that workers could get to the countryside

on their one day off per week, Sunday. Manchester and other industrial towns,

though highly urbanized at this period, were nevertheless surrounded by pretty

and much cleaner countryside. This railway map of South Yorkshire and Lancashire

shows the extent of the open country surrounding the great cities, as well as

the railroad connections and spur lines in the area.

Click

on image for larger view

Mounds where the grass was rank and high, and

where brambles, dock-weed, and such-like vegetation, were confusedly heaped

together, they always avoided, for dismal stories were told in that country

of the old pits hidden beneath such indications.

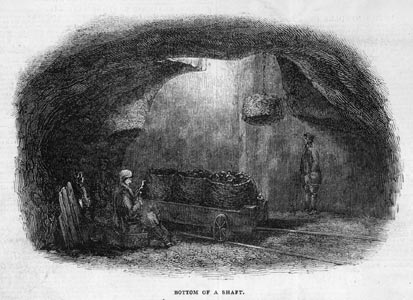

The industrial areas in the north of England, as well

as the midlands, had been heavily used as mining areas and were dotted with

old, disused mines, many of them unmarked or poorly indicated. As Rachael and

Sissy know—and as we see all too clearly in the course of the chapter—these

deep, disused mine shafts could be extremely dangerous. On April 15, 1843, the

Illustrated London News published this illustration of a mine shaft that

was still in use. Note how the light just barely filters down, indicating that

the vertical shaft is quite deep.

a candle was sent down to try the air

One of the many dangers of mining was that poisonous

gases could collect in underground shafts. Sending a candle down the shaft tested

for the presence of oxygen. If the candle stayed lit, then breathable air was

present. However, since some of these gases were combustible (as in the later

reference to "fire-damp," safety lamps were used for lighting in the

mines.

"I ha' fell into th' pit, my dear, as have

cost, wi'in the knowledge o' old fo'k now livin', hundreds and hundreds o' men's

lives…. I ha' fell into a pit that ha' been wi' the' fire-damp crueler than

battle. I ha' read on ‘t in the public petition, as onnyone may read, fro' the

men that works in pits, in which they ha' pray'n and pray'n the lawmakers for

Christ's sake not to let their work be murder to ‘em…"

Fire-damp, a combustible gas, caused deadly explosions

in coal mines. Stephen here refers to the movement in the 1840s, which Dickens

had strongly and publicly supported, to improve safety measures in coal mines.

Dickens also referred to mining safety in several Household Words articles.

Rescued by a savage old postillion who happened

to be up early, kicking a horse in a fly

A postillion is a guide for a coach or other hired conveyance; a fly was a one-horse

carriage, available for hire.

A Grand Morning Performance by the Riders,

commencing at that very hour

A "morning performance" did not necessarily mean that it took place

before noon; at the time, "morning" often was used informally to mean

the part of the day before dinner, and thus a morning performance took place

in the afternoon. The word now used for such a performance is matinee, derived

from the French word matin (morning).

The Emperor of Japan, on a steady old white

horse stenciled with black spots

At the time that Hard Times was written, Japan was entirely closed to

foreigners. The Emperor of Japan was thus a suitably exotic and unknown personage

for the subject of a circus act. Several such performances at the time made

reference to Japan and the Japanese. Later in the century, as Japan opened somewhat

and the British became more interested in trade with the country, a craze for

Japanese art and design would take place, but in the 1850s this was still years

away.

if you don't hear of that boy at Athley'th,

you'll hear of him at Parith.

Astley's Royal Amphitheatre was the best-known circus of the day in England,

having been established in 1768. Although it changed venues and names several

times, it was extremely influential in changing the modes of performance in

the English circus, incorporating entertainment of all sort, from clowns to

equestrian acts. There were several well-known circuses in Paris, among them

the Cirque d'Été and the Cirque d'Hiver.

Our Children in the Wood, with their father

and mother both a-dyin' on a horthe—their uncle a-retheiving of ‘em ath hith

wardth, upon a horthe—themthelvth both a-goin' a-blackberryin' on a horth—and

the Robinth a-coming in to cover 'em with leavth, upon a horthe

This horseback act is a faithful rendition of the plot of a traditional English

ballad, the story of the Babes in the Wood, which was the basis for pantomime

and circus acts throughout the nineteenth century.

"Thath'th Jack the Giant-Killer—piethe of comic infant bithnith"

"Jack the Giant-Killer" was a popular fairy tale and thus the basis

for an act in Sleary's Circus.

"Your brother ith one o' them black thervanth."

Performances in blackface, considered comic at the time, were fairly common

in nineteenth-century circuses and other entertainments.

"There'll be beer to feth. I've never

met with nothing but beer ath'll ever clean a comic blackamoor."

Beer was indeed used to clean the faces of those who worked in blackface. Originally

burnt cork was used for blackening the face, but by the mid-nineteenth century

boot-blacking was frequently used. The derogatory term "blackamoor"

dates from the sixteenth century and derives from the use of the term Moor for

a black person.

Had he any prescience of the day, five years

to come, when Josiah Bounderby of Coketown was to die of a fit in the Coketown

street, and this same precious will was to begin its long career of quibble,

plunder, false pretences, vile example, little service and much law?

Lawsuits and disagreements over wills were often extremely protracted in the

nineteenth century, owing to the intricacies of the Court of Chancery, which

handled estate law. Dickens had made this problem the major theme of his previous

novel, Bleak House. At the time he wrote, however, Chancery was undergoing

a series of reforms that simplified court procedure in an attempt to address

the problem.