![]()

NOTES ON ISSUE 6: GLOSSARY

"Oh, my friends,

the down-trodden operatives of Coketown! Oh, my friends and fellow-countrymen,

the slaves of an iron-handed and a grinding despotism! Oh, my friends and fellow-sufferers,

and fellow-workmen, and fellow-men! I tell you that the hour is come when we

must rally round one another as One united power…"

Dickens's union orator, Slackbridge, whose words open this installment of Hard

Times, is partly based on Dickens's own observations during the 1853-54

strike in Preston, a Lancashire cotton town. One of its leaders, Mortimer Grimshaw,

inspired the portrayal of Slackbridge, which is notable for Dickens's air of

hostility toward the union leader—despite his support for the workers' plight

generally.

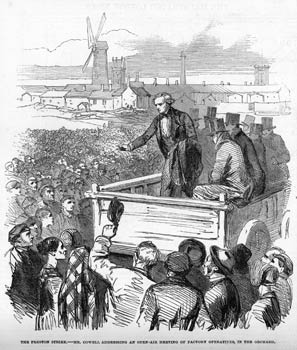

The lengthy Preston strike was heavily covered in the press at the time. Another

prominent (and less inflammatorily radical) leader of the strike, George Cowell,

was depicted speaking to the striking workers in the Illustrated London News

of November 12, 1853, as shown below.

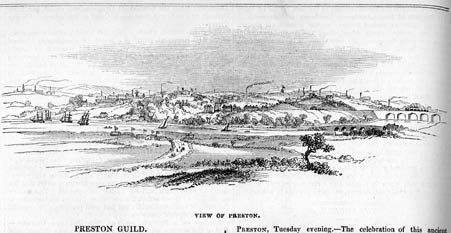

The illustration was titled "The Preston Strike—Mr. Cowell addressing an open-air meeting of factory operatives in the Orchard." A view of the town of Preston itself appeared in the Illustrated London News on September 10, 1842.

"Good!" "Hear, hear, hear!"

"Hurrah!" and other cries, arose in many voices from various parts

of the densely crowded and suffocatingly close Hall, in which the orator, perched

on a stage, delivered himself of this and what other froth and fume he had in

him.

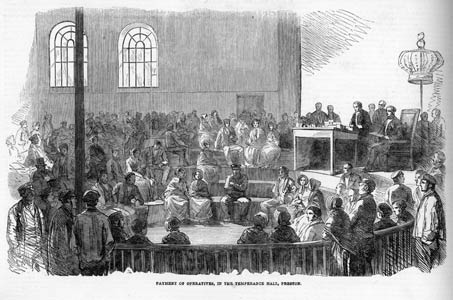

The "hall" Dickens describes here is based

on the Temperance Hall in Preston, which he saw on his stay in Preston. During

the strike there, workers regularly held meetings of delegates in the hall on

Sundays, and on Mondays the striking workers received their relief payments

there. This depiction of Temperance Hall during the strike, showing the distribution

of these payments, appeared in the Illustrated London News on November

12, 1853.

resolve for to subscribe to the funds of the

United Aggregate Tribunal, and to abide by the injunctions issued by that body

for your benefit, whatever they may be

At the time Dickens wrote, unions tended to be occupation-specific.

In the Lancashire cotton industry, for instance, there were associations for

power loom weavers, spinner, and so on, some of which were short-lived. During

the Preston strike, however, the various trade unions of the area worked cooperatively

and with efficiency to coordinate their demands. Here, the union organizer Slackbridge

seems to be calling for a general union that would bring all the trades together

into a "united aggregate tribunal." Dickens, who drew heavily on his

observations of the Preston strike for this episode, may also have been thinking

of a strike of engineers that took place in 1852. That strike was called by

a large and prestigious union, the Amalgamated Society of Engineers, which was

portrayed in the press as despotic.

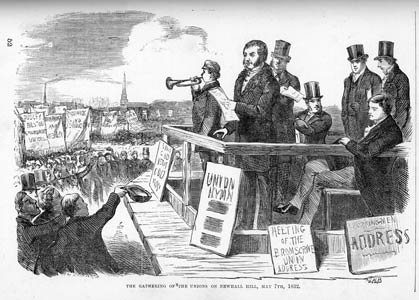

The idea that smaller unions might combine into large and extremely powerful

organizations across many trades, industries and regions fed bourgeois Victorian

fears of a workers' revolt. Here, Slackbridge's rhetoric may underscore that

fear, as he calls upon the workers to join and to "abide by the injunctions"

issued by the union, "whatever they may be." Nevertheless, workers

and organizers had from an early time seen the benefit in working cooperatively,

and they would continue to do so. One large union meeting, which took place

in Birmingham in 1832, is depicted in Robert Kirkup Dent's Old and New Birmingham

(1880).

Castlereagh existed

Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh, was Britain's Foreign

Secretary from 1812-1822. He was seen as responsible for the decision to mobilize

troops during a peaceful meeting of 80,000 people in favor of parliamentary

reform outside Manchester in August 1819. Eleven people were killed and 400

injured in the Peterloo Massacre. His name thus became a byword for treachery

and oppression among the working classes. Castlereagh committed suicide in 1822,

and crowds followed his funeral procession through the London streets, cheering.

"…there'll be a threat to turn out if I'm let

to work among yo."

To "turn out" is to strike. Stephen is here

referring to the common practice of unions setting up a closed shop. The unions'

demands to prevent unskilled, nonunion labor from working among them was a major

issue and the cause of strikes in the 1850s, but Dickens—unlike many industrial

novelists of the day—had no wish to portray an actual strike.

"I who ha worked sin I were no heighth at

aw"

The Factory Act of 1819 (when Stephen would have been

about five years old) made it illegal to employ children under nine in factories.

However, as with other laws regulating industry, factory owners sometimes simply

ignored such regulations. Further restrictions had been placed on child labor

in 1833 and 1844, including the requirement that working children be given some

schooling.

"Had not the Roman Brutus, oh, my British countrymen,

condemned his son to death; and had not the Spartan mothers, oh, my soon to

be victorious friends, driven their flying children on the points of their enemies'

swords?"

Lucius Junius Brutus, founder of the Roman Republic in

509 B.C. and first Consul of Rome, had his two sons put to death for conspiring

against the state. The Spartans were notorious for being trained never to retreat

in battle, so Spartan mothers would encouraged their sons to sacrifice themselves

rather than retreat.

fugleman

A soldier trained to march at the front of a regiment,

to serve as an example or model to the troops.

sent to Coventry

Alienated or ostracized. The origin of the term is uncertain,

but Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable gives the following explanation:

According to Messrs. Chambers (Cyclopedia), the citizens of Coventry had at one time so great a dislike to soldiers that a woman seen speaking to one was instantly tabooed. No intercourse was ever allowed between the garrison and the town; hence, when a soldier was sent to Coventry, he was cut off from all social intercourse.

"a set of rascals and rebels whom transportation

is too good for!"

Transportation was the practice of sending convicted

criminals to overseas penal settlements, most notably Australia. Dickens used

transportation as a plot device in Great Expectations; the practice

ended in 1868.

"fur to weave, an' to card, and to piece out

a livin'"

Carding involved raking raw, partially cleaned cotton

into parallel fibers, preparatory to spinning it into thread. Those who worked

in carding rooms were often subject to lung complaints (see Issue 5). The phrase

"piece out a livin" may allude to the practice of paying workers by

the piece instead of by the hour.

"goes up wi' yor deputations to Secretaries

o' State 'bout us…"

In January, 1854, mill-owners and manufacturers sent

a deputation to Lord Palmerston, the Home Secretary, to protest new manufacturing

regulations.

"we'll indict the blackguards for felony, and

get 'em shipped off to penal settlements."

Union organizers and laborers were indeed transported

for various trumped-up offenses. The so-called Tolpuddle Martyrs (six workers

from the town of Tolpuddle, accused of trade unionism) were sentenced in 1834

under the 1797 Act against Unlawful Oaths. They were transported but subsequently

pardoned and allowed to return to England. Closer to the time Dickens was writing,

in March 1854, labor delegates in Preston had been arrested on charges of conspiracy,

although the charges were subsequently dropped.

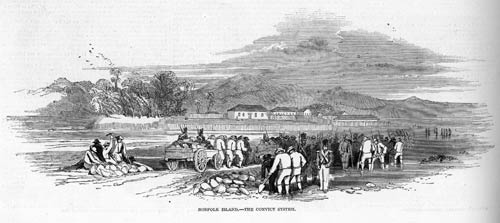

Norfolk Island

A particularly remote and harsh penal settlement, some 1000 miles off the coast

of Australia. Transportation to Norfolk Island was reserved for the worst offenders

(often those who had committed second crimes while in custody in Australia),

and conditions there were dreadful. Its use as a penal colony was discontinued

in 1855.

This illustration of Norfolk Island appeared in the Illustrated London News

on June 12, 1847:

"The strong hand will never do 't. Vict'ry

and triumph will never do 't. Agreeing fur to mak' one side, unnat'rally awlus

and forever right, and toother side unnat'rally awlus and forever wrong will

never, never do 't. Nor yet lett' alone will never do 't."

In February 1854, Dickens published an article called

"On Strike" in Household Words, which concluded with words

to similar effect:

...in the gulf of separation it hourly deepens between those whose interests must be understood to be identical or must be destroyed, it is a great national affliction. But, at this pass, anger is of no use, starving out is of no use…. Masters right, or men right; masters wrong, or men wrong; both right, or both wrong; there is a certain ruin to both in the continuance or frequent revival of this breach. And from the ever-widening circle of their decay, what drop in the ocean shall be free!

the Travellers' Coffee House down by the railroad

Refreshment houses and waiting rooms in or near railway

stations were commonplace by the 1840s, replacing coach inns.

The bread was new and crusty, the butter

fresh, and the sugar lump, of course

In Victorian times, sugar was sold in hard loaves, not

finely granulated. The foods mentioned—good bread, fresh butter, and more expensive

white sugar—indicate that Stephen has access to (and money for) decent, though

limited foods, particularly when he is entertaining guests. The adulteration

of food and the poor quality of food sold to the poor—including rancid butter,

heavy or adulterated bread, and tea that was reused or cut with other ingredients—was

a problem in the nineteenth century, particularly in large cities.

so large a party necessitated the borrowing

of a cup

It was commonplace for laborers to have no more dishes,

cutlery, or furniture than would meet the immediate needs of their own households,

because of the expense of such objects.