![]()

NOTES ON ISSUE 8: GLOSSARY

Her father was usually

sifting and sifting at his parliamentary cinder-heap in London (without being

observed to turn up many precious articles among the rubbish), and was still

hard at it in the national dust-yard.

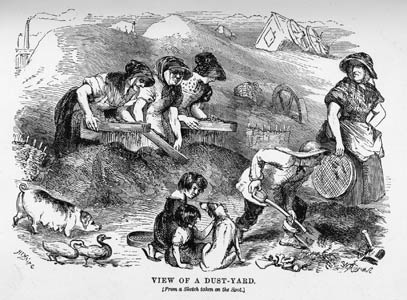

Heaps of dust-yards (that is, garbage dumps) surrounded London, largely composed

of ashes from the many coal fires in the metropolis's homes. They were literally

"sifted" by the very poor, who were looking for valuables as well

as any saleable material. According to Henry Mayhew's London Labour and the

London Poor, a great amount of the city's trash was reusable and could be

sold: old boots and shoes were sold to manufacturers of Prussian blue, bricks

and oyster shells went to builders (for foundations) and road-builders, cinders

went to brick-makers for burning bricks, and fine soil went to brick-makers.

Mayhew includes this illustration, which shows the dust-sifters at work.

anchorite

A hermit.

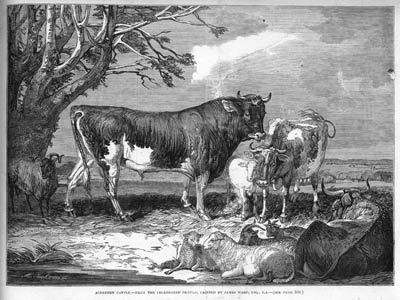

Alderney

Alderney cattle were a breed of dairy cow from the Channel

Islands, known for their milk (like the better-known Jersey cattle). This illustration

of Alderney cattle appeared in the Illustrated London News on December

9, 1848.

"He is shooting in Yorkshire," said

Tom. "Sent Loo a basket half as big as a church, yesterday."

Shooting at country estates was a seasonal hobby for

the upper classes, who shot such game as grouse, partridges, and pheasant on

the property of large land owners during the autumn and winter hunting seasons.

Tenants on the estates were generally not allowed to hunt for such game; their

leases reserved it for the squires and nobility who owned the land. Baskets

of game, therefore, were a special treat for those connected with the upper

class.

The Illustrated London News frequently marked the hunting season with

an illustration of shooting. This engraving depicting a pheasant-shooting party

appeared on February 4, 1843.

she was so quick in pouncing on a disengaged coach,

so quick in darting out of it, producing her money, seizing her ticket, and

diving into the train, that she was borne along the arches spanning the land

of coal-pits past and present as if she had been caught up in a cloud and whirled

away

Mrs. Sparsit's impromptu train journeys in this episode

show the degree to which local as well as national travel had been speeded by

the vast growth of the railways in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Throughout this chapter, the plot of Mrs. Sparsit's pursuit of Louisa depends

on the frequent availability of fast local transit.

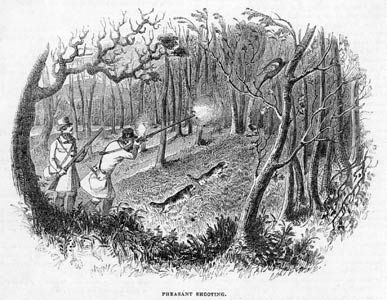

A mid-nineteenth-century map drawn by J. Bartholomew, Jr., "Railway Map

of the British Isles exhibiting all the Railways & Canals in England, Scotland

& Ireland completed or in progress with their respective stations," shows

the extent of the railway network in Britain at around the time Hard Times

was written.

Click

on image for larger view

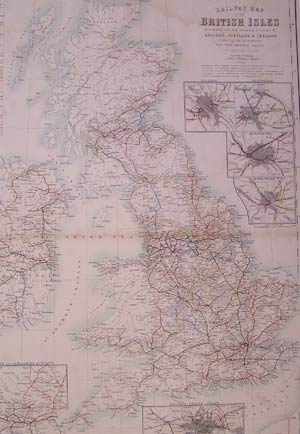

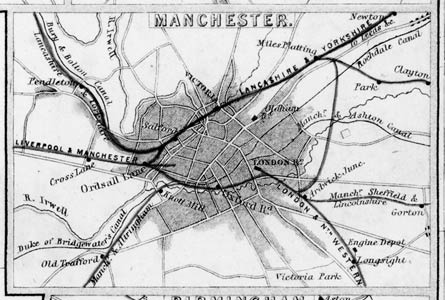

The following detail from the same map shows the extent of the local railways surrounding Manchester.

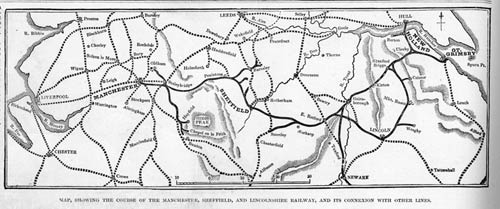

A few years before the writing of Hard Times, on April 15, 1848, the Illustrated London News printed an illustration of the railway network in the same region, extending from Liverpool and Manchester to Sheffield to Lincolnshire.

Click

on image for larger view

the electric wires which ruled a colossal strip

of music-paper out of the evening sky

Electric wires lined the railways as far north as Glasgow by 1840; after the

mid-1840s, telegraph poles became more and more common as well. Thus electrical

lines were a common sight from train windows at the time of the novel's composition.

The national dustmen

That is, Members of Parliament. For more on the comparison of Parliamentary

work to dust-heaps, see note above.