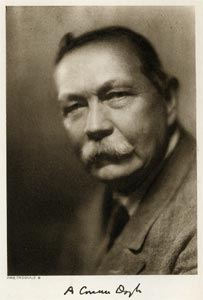

Arthur Conan Doyle

Like the elusive Sherlock Holmes, his most famous creation, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a man of many contradictions. Scientifically educated, he believed in sťances and fairies. An advocate for more equitable divorce laws, he believed that women should be denied the vote. A humanist who identified with oppressed peoples, he staunchly defended English colonialism at its most aggressive. He dreamed of being a serious historical novelist, yet he is best remembered for stories that he considered pot-boilers. The product of a pragmatic, fiercely protective mother and a detached dreamer of a father, Conan Doyle became a man with astonishing self-confidence, a tireless self-promoter who also retained some measure of childish innocence throughout his life.

|

Arthur Conan Doyle

at 4 years old |

Arthur Conan Doyle's humble beginnings did not predict his future success. Born on May 22, 1859, to a middle-class, Catholic family, he grew up on Edinburgh's rough-and-tumble streets, far from his successful grandfather and uncles, who hobnobbed with London's intellectual elite. His celebrated grandfather, John Doyle, had reinvented the art of political caricature. John Doyle's eldest son, also named John, became a well-known caricaturist himself, and the second son, Richard, began his career as a successful cartoonist for Punch (an early magazine devoted to political satire) and ended it as a famous book illustrator. Two other sons were also successful in different fields.

Arthur's parents, Mary Foley Doyle and Charles Altamont Doyle, had moved to Scotland from London, hoping that Charles could advance his career in architecture. Having inherited some measure of his family's artistic talent, Charles began with every hope of success, but never realized his dreams. Plagued by depression and alcoholism, Charles was a distant father and husband, becoming so detached from reality that he ended life in an asylum. With considerable charity, his son Arthur later said of him, "My father's life was full of the tragedy of unfulfilled powers and of underdeveloped gifts."

As the only active parent, Mary

Doyle had a strong influence on Arthur, the eldest surviving son

of seven children, instilling in him a love of chivalric romances

and a firm belief in the English code of honor. She made the boy

memorize and recite his family's genealogy, ancestor by ancestor.

When left to himself, Arthur loved to read American "wild west"

adventure stories, especially those of Bret Harte and Thomas Mayne

Reid, an Irish immigrant to the U.S. who wrote The Scalp Hunters

(1851), young Arthur's favorite book. As an adult, Conan Doyle felt

that the highest vocation he could pursue as a writer was to create

well-researched historical romances idealizing British history.

The Doyles sent Arthur to an austere Jesuit school for his early

education. Despite the Spartan fare and harsh discipline, Arthur

excelled. When Arthur left the Jesuits, Mary Doyle persuaded him

to pursue a medical degree at the University of Edinburgh. Arthur

agreed, more out of a practical desire for a reliable profession

than out of passion for the subject.

|

| Arthur at 14 holding

|

|

The medical school

graduate at 22 |

By this time, Charles Doyle had lost his job, and the family had difficulty paying the school fees. A lodger named Bryan Charles Waller became the family's protector, eventually supporting Mary, Charles, and their children completely.

|

Dr. Joseph Bell |

Once at university, Conan Doyle found the work difficult and boring. He gained more amusement from playing sports, at which he excelled, than in listening to lectures in large, crowded lecture halls. More interesting than studying was describing his instructors' eccentric personalities. Among his teachers was the man Conan Doyle later acknowledged as his inspiration for Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Joseph Bell. Dr. Bell taught his students the importance of observation, using all the senses to obtain an accurate diagnosis. He enjoyed impressing students by guessing a person's profession from a few indications, through a combination of deductive and inductive reasoning, like Holmes. Although Bell's methods fascinated Conan Doyle, his cold indifference towards his patients repelled the young medical student. Some of this coldness found its way into Sherlock Holmes's character, especially in the early stories.

Around the time he obtained his medical degree,

Conan Doyle's crisis of faith, which had been brewing since his

days with the Jesuits, came to a head. He announced to his uncles

that he had turned away from organized religion, shocking them deeply

and causing them to withdraw their support. Because he refused to

practice his family's religion, Conan Doyle was forced to make own

way in the medical profession, with neither financial help nor letters

of introduction to influential people. He was an uneasy agnostic,

however, and although he hoped that pure rationalism could take

the place of religion for him, it never did. Around 1880, he began

to attend sťances, and by the end of his life he had become an ardent

spiritualist.

A restless man who loved adventure and physical activity, Conan

Doyle took any opportunity to travel. He grew interested in photography

and published several articles about it. To make a few extra pounds

while studying medicine, he hired on as ship's doctor on brief voyages

to the Antarctic and Africa. He also began to write short stories

for sale, based on the adventure tales he had loved as a child and

on his own first-hand experiences. After graduation, he struggled

to establish a medical practice, since he could not afford to buy

one. Although hampered by poverty and his lack of social connections,

Conan Doyle achieved a modest success in medicine. His 1885 marriage

to Louise Hawkins, the sister of a patient who had died, provided

him with a small supplemental income that raised his standard of

living.

|

|

In 1886, Doyle finished the first Sherlock Holmes

novella, A Study in Scarlet. After several rejections,

he was forced to sell it outright for £25 for inclusion in

the 1887 Beeton's Christmas Annual, a holiday collection that often

sold out, but did not usually attract much attention in the national

press. The work was reprinted in 1889 and many more times, but Conan

Doyle never earned another penny from it. Sign of the Four,

the second work to feature Holmes and Watson, also achieved a small,

but by no means brilliant, success.

While writing the early Holmes stories, Doyle also began what he considered his most important work: chivalric, historical novels based on British history, primarily, Micah Clark, Sir Nigel, and The White Company. Although these novels were widely admired, none of them created the stir caused by the first series of short stories featuring Sherlock Holmes and John Watson that appeared in The Strand Magazine, starting in 1891. Despite their overwhelming success, Conan Doyle never suspected that these stories would be the foundation of his literary legacy.

|

Arthur Conan Doyle in

1891, the year Holmes made him a celebrity |

After writing three series of twelve Holmes stories,

receiving the unheard-of sum of £1000 for the last dozen, Conan

Doyle was sick to death of the popular detective and decided to kill him

off in the 1893 story, "The Final Problem." Conan Doyle considered the

Holmes stories light fiction, good for earning money, but destined to

be quickly forgotten, the literary equivalent of junk food. "I couldn't

revive him if I would, at least not for years," he wrote to a friend who

urged Holmes's resurrection, "for I have had such an overdose of him that

I feel towards him as I do towards pâté de foie gras,

of which I once ate too much, so that the name of it gives me a sickly

feeling to this day." The vehement public reaction to Holmes's death must

have shocked Conan Doyle. People wore black armbands and wrote him pleading--or

threatening--letters. Still, it was nine years before he capitulated to

public opinion and brought Holmes back.

The third Holmes novel, The Hound of the Baskervilles, appeared

in nine parts in The Strand Magazine during 1901-2, but it was

presented as an old case from Watson's records, completed before Holmes's

death. Conan Doyle did not make up his mind to resurrect Holmes until

1903, when he wrote "The Empty House." He continued, reluctantly, to produce

Holmes stories until 1927, three years before his own death.

Conan Doyle became an important public figure, twice standing (unsuccessfully)

for Parliament. He was knighted for his efforts on behalf of the Boer

War, both as the author of a persuasive, pro-war book and as a volunteer,

caring for wounded British soldiers in the field. He even took on several

real-life mysteries, using Holmes's methods and his own status as a famous

author to free two unjustly imprisoned men.

The First World War tore apart Conan Doyle's familiar world. Like so many

others, he lost close family members to the conflict. Conan Doyle's brother-in-law

and nephew died in combat, while the influenza pandemic took his brother

Innes and his eldest son Kingsley, weakened by war wounds. During the

war, he managed to have himself appointed as an observer for the Foreign

Office, but he was kept away from the horrors of the western front for

fear that he might reveal to the public things that the military would

rather have kept quiet. Even Sherlock Holmes served England in the war.

In the story that Conan Doyle intended to be the last Holmes outing, His

Last Bow, published in 1916, Holmes outwits a German spy.

Conan Doyle found a refuge from the horrors of the war, and he clung to

it tenaciously. Starting in 1916, he publicly declared himself a spiritualist,

and over the next few years he made spiritualism the center of his life,

writing on the subject and traveling all over the world to advocate his

beliefs. Never afraid to take an unpopular stand, Conan Doyle wrote a

book in 1922 called The Coming of the Fairies, in which he defended

the veracity of two young girls who claimed to have photographed each

other playing with actual fairies and goblins.

|

Frances Griffiths

and "friends" |

Towards the end of their lives, long after Conan Doyle's death, the aged "girls" admitted to having used paper cutouts as stand-ins for the fairies. Interestingly, Conan Doyle's own Uncle Richard had invented, in his book illustrations, the typical representation of a fairy as a little girl with dragonfly wings and a gossamer gown. No matter how many times Conan Doyle was tricked by mediums later proven to be dishonest, he continued to believe in spiritualism. The famous American magician Harry Houdini made a project of trying to convince Conan Doyle of his error, but all he managed to do was ruin their friendship. Houdini saw spiritualism as cruel because it gave people false hope; Conan Doyle, who was already suffering from serious heart disease, wanted to believe that death was a grand new adventure. He fought his infirmity, trying to continue writing and traveling as before. He died at the age of 71, secure in his spiritualist beliefs.

|

Conan Doyle in

the last year of his life |

Doctor, writer, believer in the supernatural--Conan

Doyle's personality encompassed all these traits that contributed to the

Sherlock Holmes stories we love to read today. Conan Doyle's fanciful

imagination, combined with his scientific training, created ideas that

have helped to shape the modern mystery and science fiction genres. One

of the first to anticipate the dangers of submarines in warfare, he wrote

a Sherlock Holmes story on the subject. His novel The Lost World

is the ancestor of Jurassic Park and countless other films. Another

of his stories, "The Ring of Thoth," was probably the plot source of the

1932 film The Mummy with Boris Karloff. An 1883 medical article

called "Life and Death in the Blood," outlining the imaginary voyage of

a microscopic observer through the human body, anticipated the main idea

behind the film Fantastic Voyage. Conan Doyle's most long-lived

idea, however, was Sherlock Holmes himself, who has continued to evolve

in our time through the works of other writers and filmmakers, taking

forms even his creator could never have imagined.

Sherlock Holmes: A Hero for His Time--and Ours

|

Street signs on Baker Street, Westminster |

As a Halloween costume, it's almost too easy--just

wear a deerstalker cap, stick a calabash pipe between your teeth,

and carry a magnifying glass. Say, "Elementary, my dear Watson."

Chances are, everyone will know that you're supposed to be Sherlock

Holmes. No matter that Holmes wore a cap only once in the original

stories, that his pipe of choice was not a calabash, and that he

never uttered that phrase. He did, however, use a magnifying glass

occasionally.

Like other pop culture icons, Holmes and Watson have evolved since

their creation over a century ago. Their characters have changed,

as have the qualities for which audiences admire them. Below appear

some of the best-known permutations of Holmes and Watson, as they

have traveled from print to stage and radio, to film and television,

and back to print again. It would be impossible to list every version

here, so some guidelines have been included for further investigation.

The game is afoot! Happy sleuthing.

The Many Faces of Holmes

The original readers of the very first Holmes story, A Study

in Scarlet, had to do with four lackluster illustrations by

D.H. Friston, but, when the novella was published in book form,

Holmes looked something like Arthur Conan Doyle's own father, Charles

Altamont Doyle--and was, in fact, the elder Doyle's creation. The

author's father created a series of vague line-drawings that unfortunately

failed to capture the excitement of the text. He gave Sherlock Holmes

his own features, including his scraggly beard. No record exists

of his son's response.

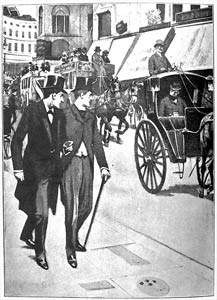

|

Holmes and Watson

on the town |

When "A Scandal in Bohemia" was published in The

Strand Magazine in 1891, readers were greeted with Sidney Paget's

moody drawings, which represent Holmes as tall, handsome, and elegant,

despite Conan Doyle's original description, according to which Holmes

was extremely thin, with a large nose and small eyes set close together.

Apparently Paget's younger brother Walter, whom the artist used

as a model, was quite a handsome fellow. Years later, after his

brother's death, Walter himself illustrated a few of Conan Doyle's

stories in The Strand.

Conan Doyle soon grew attached to Sidney Paget's elegant vision

of Holmes, and when he met the American actor William Gillette,

who wanted to play Holmes on the stage, he felt that his creation

had come to life. Pictures of Gillette as Holmes, wearing the famous

dressing gown, can be found at the "221B Baker Street" website (ed.

Sherry Franklin): www.sherylfranklin.com/sh-gillette.html.

|

Holmes is balding

in J. Frank Wiles's illustration from The Valley of Fear |

Others, such as the American illustrator Frederic

Dorr Steele, who based his Holmes on William Gillette, also created

a compelling vision of the detective and his world. Holmes usually

remained tall and thin, but not always young or handsome.

Holmes and Watson were well-represented on the radio, too. See "The

Sherlock Society of London" website for a list of radio plays (including

some stories not written by Conan Doyle) that can be downloaded

in MP3 format: www.sherlock-holmes.org.uk/radio.php.

Later radio versions with John Gielgud as Holmes, Ralph Richardson

as Watson, and Orson Welles as Professor Moriarty, can be found

on the "Valley of Fear" website: www.cambridge-explorer.org.uk/HBWEB/VV341/JG-RR-Home.htm

(ed. Hugo Brown).

Holmes in Film

During Conan Doyle's lifetime, silent film versions of the Sherlock

Holmes stories were made in England and the U.S. In the U.S, John

Barrymore played Holmes in a film based on one of Gillette's stage

plays, and British actor Ellie Norwood played Holmes in 47 silent

films between 1920 and 1923. Typing "Sherlock Holmes" into the search

engine of the "Internet Movie Database" at www.imdb.com

will retrieve hundreds of titles, including drama, comedy, pastiche,

cartoons, and all sorts of other stories that borrow the characters

of Holmes and Watson.

"Gaslight on the Web" contains links to a photo gallery of some

of the many actors who played Sherlock Holmes on the stage and in

film: www.mindspring.com/~tjbayne4/photogl.htm

(ed. Tom Bayne). "Sherlockian.net" also maintains links to sites

about actors who portrayed Sherlock Holmes on radio, TV, film, and

stage: www.sherlockian.net/stage/index.html

(ed. Chris Redmond).

The two best-known Holmes of our time are probably Basil Rathbone

and Jeremy Brett. Rathbone played Holmes alongside Nigel Bruce,

as a rather doddering Watson, in 14 films between 1939 and 1946;

some were filmed adaptations of Conan Doyle's stories, while others

used newly created plots. In the 1980's, Jeremy Brett acted opposite

two excellent Watsons, David Burke and Edward Hardwicke, in 36 episodes

and four films produced by Granada Television in England and shown

on PBS. Most are available on DVD.

Further Adventures

Search for "Sherlock Holmes" on any internet bookseller's site,

and thousands upon thousands of titles will appear. Since Conan

Doyle's time, writers have been tempted to create their own tales

using Holmes as inspiration. Every Holmes is different. Some authors

concentrate upon Holmes's drug addiction or have him meet a famous

historical figure (Nicolas Meyer's The Seven-Percent Solution

does both). Some focus on his relationship with Watson, while others

invent a lady-friend for him or choose a female acquaintance from

the books to be his paramour. Sometimes Moriarty returns, sometimes

Holmes's brother Mycroft. Occasionally Holmes acquires offspring.

In the past two years alone, at least two dozen novels or short

story collections have come out, not to mention several new editions

of the original works.

Here are some recent fictional treatments: Caleb Carr's The Italian

Secretary (Carroll & Graf, 2005) takes Holmes and Watson into

the realm of the supernatural. In Mitch Cullin's A Slight Trick

of the Mind (Nan A. Talese, 2005), Holmes is in his nineties

and has become rather forgetful. Laurie King's series (published

by Bantam) portrays an aging, but still vital, Holmes and his young

wife. Thos. Kent Miller in The Great Detective at the Crucible

of Life (Wildside Press, 2005) involves Holmes in a Rider Haggard

story in Africa, and Sherlock Holmes and the Search for Excalibur

(Authorhouse, 2005) winds up a trilogy by Luke Steven Fullenkamp

in which Holmes and Moriarty seek the famous sword. (If that seems

far-fetched, consider this: in a 1958 short story called "The Martian

Crown Jewels," science-fiction author Poul Anderson sent Holmes

to Mars.) Some authors focus on Mrs. Hudson, Holmes and Watson's

faithful landlady, or on other minor characters. Others stay busy

figuring out what Holmes did during those years between "The Final

Problem" and "The Empty House," when Watson thought him dead.

For those who want to return to the source, a new version of the

original writings is now available: The New Annotated Sherlock

Holmes has come out in three volumes, two for the short stories

and a third for the novels. It is edited by Leslie S. Klinger and

published by Norton. One caveat: the notes and commentary all play

"the Grand Game," and assume that Holmes and Watson were real people.

The Grand Game

What do we really know about Holmes? Who is he? Where was he born,

who were his parents, where did he go to school? Is he English?

French? American? These questions are irrelevant, you might argue,

because we know that Holmes is a literary character, not a real

person. A large group of dedicated people from all over the world

might not agree. They call themselves Sherlockians, and they play

at "the Grand Game," according to which Holmes and Watson are real

people and Conan Doyle is their rather incompetent literary agent.

In 1912, Ronald A. Knox, a detective-story writer and Catholic priest,

wrote an article called "Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes,"

in which he satirized the ponderous jargon of literary criticism.

The article's assumption that Sherlock Holmes was a real person

caught the fancy of writer and editor Christopher Morley, who formed

a Sherlockian club called the Baker Street Irregulars that continues

to meet today. Their website can be found here: www.bakerstreetjournal.com.

Other Sherlockian societies with their own publications also exist

and can be found on the web.

|

The Sherlock Holmes Museum in Meiringen, Switzerland, claims to be the most authentic

Baker Street reproduction in the world |

Conan Doyle wrote the Holmes stories quickly, never imagining that they would receive much scrutiny. If he forgot a date or fact from a previous story, he forged ahead without looking it up. This bad habit has resulted in some startling discrepancies. Was Watson wounded in the leg or the arm? How could Watson's deceased wife be on a visit to her mother's? Is Watson's given name "James" or "John"? To correct these and other inconsistencies, Sherlockians comb the "canon," or "sacred writings," for clues, seek secondary sources (inventing some themselves when all else fails), and write "scholarly" articles, using Holmes's methods to solve contradictions in the works or following clues to add new "facts" to Holmes's and Watson's biographies.

When

this map was drawn in 1892, no 221b Baker Street existed

|

One favorite Sherlockian controversy centers on the "original" location of 221b Baker Street, a non-existent address in Conan Doyle's time. When Baker Street was renumbered during the 1920s, 221b was created on the block formerly called Upper Baker Street. Many faithful representations of the sitting room at 221b Baker Street have been constructed throughout the world. All contain the violin, the tobacco-holding Persian slipper, and other Holmesian accouterments mentioned in the stories.

The Game is played seriously, but is played best when it avoids pomposity. Christopher Morley once wrote, "What other body of modern literature is esteemed as much for its errors as its felicities?" Conan Doyle, on the other hand, wondered why anyone "should spend such pains on such material." He alone, it seems, was immune to the fascination exerted by Sherlock Holmes and John Watson on generations of readers.