|

|

"The Adventure of the The Greek Interpreter" |

Notes l Bibliography l Download Issue 5

I had never heard him refer to his relations, and hardly ever to his own early life. (1)

This reticence on the part of Sherlock Holmes has allowed years of fertile speculation among novelists and Sherlockians.

...the causes of the change in the obliquity of the ecliptic.... (1)

The earth's orbit stays in a plane called the "ecliptic." An imaginary axis passing through the earth's north and south poles is not perpendicular to this plane, but tilts at an angle of just over 23 degrees. This tilt is known as the "obliquity of the ecliptic." At various times in earth's long history, the angle has changed, as evinced by the orientation of magnetic minerals in geologic strata.

In A Study in Scarlet, Watson, while endeavoring to figure out Holmes's profession, makes a list of his strengths and weaknesses:

Sherlock Holmes—his limits 1. Knowledge of Literature.—Nil. 2. Philosophy.—Nil. 3. Astronomy.— Nil. 4. Politics.— Feeble. 5. Botany.—Variable. Well up in belladonna, opium, and poisons generally. Knows nothing of practical gardening. 6. Knowledge of Geology.—Practical, but limited. Tells at a glance different soils from each other. After walks has shown me splashes upon his trousers, and told me by their colour and consistence in what part of London he had received them. 7. Knowledge of Chemistry.—Profound. 8. Anatomy.—Accurate, but unsystematic 9. Sensational Literature.—Immense. He appears to know every detail of every horror perpetrated in the century. 10. Plays the violin well. 11. Is an expert singlestick player, boxer, and swordsman. 12. Has a good practical knowledge of British law.

Apparently Holmes's knowledge of astronomy is far from nil, but, at the time, Watson wasn't very well acquainted with his roommate.

...the question of atavism and hereditary aptitudes. (1)

"Atavism," or the idea of the "throwback," no longer is given credence by today's scientific establishment. In contrast, the idea that some aptitudes can be inherited now has a strong basis in the science of genetics. For a discussion of atavism in the work of 19th-century Italian scientist Cesare Lombroso, see the notes accompanying chapter 7 of our archived novel The Hound of the Baskervilles. Lombroso believed that criminal "types" were "throwbacks" to an earlier stage of evolution. That criminal behavior might have been encouraged by economic deprivation or a lack of education seems not to have occurred to him.

The point under discussion was how far any singular gift in an individual was due to his ancestry, and how far to his own early training. (1)

Watson raises one of the eternal human questions: are an individual's gifts the result of his inherited traits (nature) or his early history and training (nurture)?

"My ancestors were country squires, who appear to have led much the same life, as is natural to their class." (1)

This is the closest we come to learning anything substantive about Holmes's family life. "Country squires" are landed gentry, much like the people Holmes and Watson encounter in "The Reigate Squire." Strangely, Holmes does not mention his parents, which has prompted some Sherlockians to conjecture that he and Mycroft were orphaned young.

"But, none the less, my turn that way is in my veins, and may have come with my grandmother, who was the sister of Vernet, the French artist." (1)

There were three painters named Vernet: landscape painter Joseph Vernet (1714-1789); his son Carle (1758-1836), painter of battle scenes and court life; and Carle's son Horace (1789-1863), who became one of the most important painters of military subjects. If Sherlock was born in 1854, as founding Sherlockian Christopher Morley has conjectured, then it is most likely Horace Vernet who was Sherlock's great-uncle. He would have been 65 at Holmes's birth.

Sherlockians have found fertile ground in the idea that Holmes's ancestry is partly French.

|

|

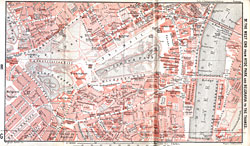

In the area between Piccadilly and Pall Mall, many clubs occupied former mansions. From Ralph Nevill, London Clubs, Their History and Treasures (London: Chatto & Windus, 1911) |

"...in the Diogenes Club, for example." (1)

The Diogenes Club is a fanciful creation of Conan Doyle's. Diogenes of Sinope (?-320 B.C.) was a Cynic—one who advocated self-sufficiency, moral excellence, and the rejection of luxury. (Perhaps the denizens of the Diogenes Club have forgotten this last precept of their namesake.) Diogenes was supposed to have wandered through the streets of his town with a lighted lantern, searching for an honest man.

...walking towards Regent Circus. (1)

"Regent Circus" is usually called "Oxford Circus." In London geography, a "circus" is a large plaza where major streets intersect. Regent Circus is south and east of Baker Street. Holmes and Watson might head towards Regent Circus, but they would want to cut south before they reached it, unless they wanted to backtrack in order to approach the St. James end of Pall Mall.

|

|

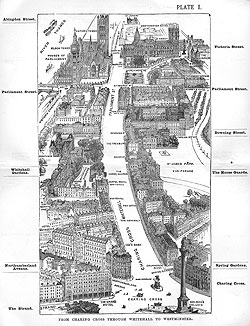

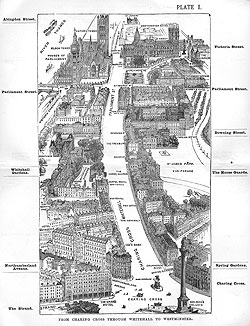

Whitehall viewed from Trafalgar Square, from Herbert Fry, London: Bird's-Eye Views of the Principal Streets, rev. ed. (London, 1892). Note Northumberland Avenue with its hotels at bottom left. |

"Mycroft lodges in Pall Mall, and he walks round the corner into Whitehall...." (2)

Pall Mall runs from Buckingham Palace to Trafalgar Square, where Whitehall also begins. Metaphorically, "Whitehall" also stands for the government, whose offices line the street, starting with the Admiralty and ending with Parliament itself.

"...and it now contains the most unsociable and unclubbable men in town. No member is permitted to take the least notice of any other one." (2)

The Diogenes Club is the opposite of most clubs, whose members wish to share their interests. Its members are "unclubbable" because they join their club to avoid society, rather than to mingle in it.

|

|

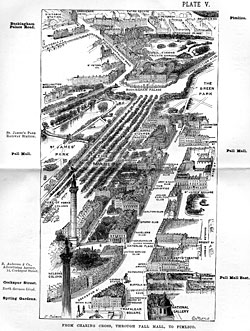

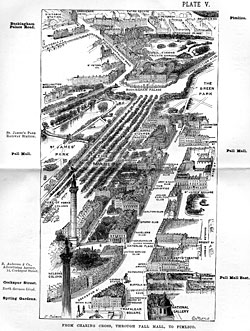

The view along Pall Mall does not, alas, show the Diogenes Club, but it does show the Carlton, which Watson says is nearby. From Herbert Fry, London: Bird's-Eye Views of the Principal Streets |

|

| The whole compass of Mycroft's universe, from Pall Mall at top left, to Whitehall at right. From Karl Baedeker, London and its Environs (Leipzig: Baedeker, 1911) |

We had reached Pall Mall as we talked, and were walking down it from the St. James' end. Sherlock Holmes stopped at a door some little distance from the Carlton.... (2)

The map at right shows the view southwest from Trafalgar Square down Pall Mall. The map just below puts the area shown by the "bird's-eye" view in the context of its surrounding streets.

"I thought you might be a little out of your depth." (3)

Mycroft is apparently the only person allowed to disparage Sherlock's talents without arousing his temper.

"To anyone who wishes to study mankind this is the spot," said Mycroft. (3)

The following exchange between Mycroft and Sherlock is one of the most beloved (and most parodied) passages in the Holmesian canon. In his memoirs (Memories and Adventures, 1924), Conan Doyle recounts a similar feat performed single-handedly by his mentor and medical school teacher, Dr. Joseph Bell, who (much to his dismay) served as Conan Doyle's inspiration for Sherlock.

"His weight is against his being a sapper. He is in the artillery." (3)

A "sapper" is a combat engineer, who, in Conan Doyle's time, was expected to dig fortifications quickly under combat conditions. Such a man would presumably need to have a sturdy, muscular build. Artillerymen were part of a crew tending cannon.

"Then, of course, his complete mourning shows that he has lost someone very dear." (3)

Although Victorian custom forced women to observe complex dress codes following the death of a loved one, men were allowed to dress basically as usual: they wore a dark suit with the addition of black gloves, hatband, and cravat. Certain elements of mourning dress were no longer obligatory as the death became more remote in time.

"...any wealthy Orientals who may visit the Northumberland Avenue hotels." (4)

Greeks, being from Eastern Europe, were considered "oriental." Northumberland Street runs east from Trafalgar Square, and, because of its proximity to the busy Charing Cross Station, is lined with hotels (see the Whitehall map, above). Today, the Sherlock Holmes Pub is located at 10-11 Northumberland Avenue.

"...my poor man with the sticking-plaster upon his face." (4)

"Sticking-plaster" is the common British term for a small adhesive bandage.

|

|

Start at Pall Mall (bottom left) to trace Latimer's "roundabout way to Kensington." Continue through Trafalgar Square, past the National Gallery, then bear right at Shaftesbury Avenue, and arrive at New Oxford Street. From Baedeker, London and its Environs (1911) |

"...and we started off through Charing Cross and up the Shaftesbury Avenue. We had come out upon Oxford Street, and I had ventured some remark as to this being a roundabout way to Kensington...." (4)

Kensington lies a good distance west and slightly south of Pall Mall, southwest of Hyde Park and Kensington Park. Instead of heading west, the coach went east on Pall Mall, north on Charing Cross Road, and hit Oxford Street, which runs east-west. This is also a roundabout way of reaching the place that Mr. Latimer wants to reach, as we see later.

"Whether these were private grounds, however, or bonâ-fide country...." (5)

Mr. Melas wonders if he is in a private park or out in "bona-fide" (Latin for "genuine" or "in good faith") country. The use of the circumflex over the "a" in the text is unusual.

|

|

Samurai armor, as seen in the British Museum in London. Photo from the Wikipedia Commons |

"...a suit of Japanese armour...." (5)

Such an artifact would not have existed in England before Anglo-Japanese trade relations began in 1854, one year after Japan was opened to Western commerce by the United States.

"'There are five sovereigns here....'" (7)

A gold sovereign is worth one pound. St. George slaying the dragon is pictured on one side, while the other shows the reigning British monarch. Five Victorian sovereigns would be worth quite a bit more than five modern British pounds. See the notes to Issue 1, "The Empty House" for a discussion of the relative worth of five sovereigns in today's currency.

"...and his lips and eyelids were continually twitching like a man with St. Vitus's dance." (7)

"St. Vitus's Dance," today called "Sydenham Chorea," is characterized by involuntary muscle movements following streptococcal infection. In the Middle Ages, it was ascribed to demonic possession and, later, to a host of other spurious causes.

"...some sort of a heathy common, mottled over with dark clumps of furze bushes." (7)

A "common" is an open area where, in former times, people were allowed to let their livestock graze freely. The common where Mr. Melas finds himself is overgrown with low-growing plants (hence the epithet "heathy"), including furze, also called "gorse," a shrub that bears yellow flowers in spring. He knows he is on a common, not out in the country, because he can see the lights of houses.

|

|

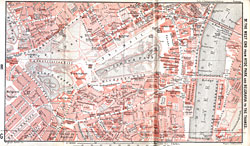

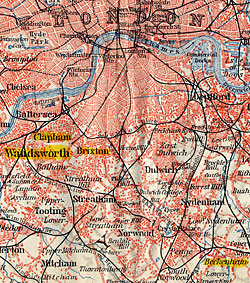

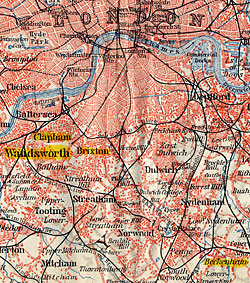

Wandsworth is southeast of central London; Clapham is marked just above it. From Baedeker, London and its Environs (1911) |

"'Wandsworth Common,' said he.

"'Can I get a train into town?'

"'If you walk on a mile or so, to Clapham Junction,' said he, 'you'll just be in time for the last to Victoria.'" (8)

Wandsworth, abutting the south bank of the Thames, is an actual town that encompasses the railway center called Clapham Junction. Historically part of the county of Surrey, Wandsworth today belongs to greater London as an outlying borough. The town has historically been a place of contrasts, including both manufacturing areas, a famous jail (where Oscar Wilde was incarcerated), and an upper-middle-class center, where Mr. Melas finds himself. Victoria Station is located in the City of Westminster.

Mycroft picked up the Daily News .... (8)

Charles Dickens founded the Daily News in 1846 and served as its first editor. Intended as a radical rival to the Morning Chronicle, it was published until 1912, and continued under other names until 1960.

"'A similar reward paid to anyone giving information about a Greek lady whose first name is Sophy. X 2473.'" (8)

"X2473" is a reference to the anonymous box number system for personal ads that most newspapers had adopted in Conan Doyle's time. Anyone replying to the box could do so to the number. The identities of both parties were protected, and the poster could screen respondents before deciding whom to trust.

"How about the Greek Legation?" (8)

A "legation" was a diplomatic outpost from a foreign country, considered a step lower than an embassy. Today the two terms are used interchangeably.

"I passed you in a hansom." (9)

The hansom cab was a common form of public transportation for those who could afford it. See a picture of a hansom cab in the notes to page 7 of "The Empty House."

"...written with a J pen on royal cream paper by a middle-aged man with a weak constitution." (9)

Mycroft is drawing conclusions about a person's age and state of health from his handwriting. See the notes to "The Reigate Squires" for a discussion of the dubiousness of such conclusions.

"'She is living at present at The Myrtles, Beckenham. Yours faithfully, J. DAVENPORT.'"

"He writes from Lower Brixton," said Mycroft Holmes. (9)

Beckenham and Brixton are quite a distance apart. Brixton, part of Lambeth, an outer borough of London, is slightly east of Wandsworth. Beckenham lies further southeast, in Kent. On the map, above, which shows the relative positions of London and Wandsworth, both Brixton and Beckenham can be found.

"It's charcoal," he cried. "Give it time. It will clear." (11)

The villains had attempted to asphyxiate Melas and Kratides by burning charcoal in a closed room—a good source of carbon monoxide.

Both of them were blue lipped and insensible, with swollen, congested faces and protruding eyes. (11)

Carbon monoxide, a molecule consisting of one carbon and one oxygen atom, has an affinity for hemoglobin, the substance in red blood cells that binds with oxygen and carries it throughout the body. When a large percentage of the body's hemoglobin is bound with CO instead of oxygen, the symptoms listed in the text are produced.

...with the aid of ammonia and brandy.... (11)

Ammonia was (and still is) used to bring someone out of a faint with its sharp odor. Brandy was used as a restorative in Victorian times, but would not be given to a sick person today, as it would tend to depress the body's systems.

...had drawn a life preserver from his sleeve.... (11)

A "life preserver" is not the familiar ring thrown to drowning sailors, but a weapon of self-defense, like the bludgeon drawn by Latimer at the beginning of the story.

...it was almost mesmeric the effect which this giggling ruffian had produced upon the unfortunate linguist...." (11)

Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815) was a German physician whose spurious theory of "animal magnetism" gathered some support in his time, but was quickly discredited after his death. His major contribution to modern medicine was his development of the ability to put his patients into a trance, enabling him to help them overcome phobias and other psychosomatic problems. The "mesmeric trance" was a forerunner of hypnotism.

Her feminine perceptions, however.... (12)

Here is Sherlock's (and Watson's) Achilles heel, once again. A person unable to recognize her (or his) own brother with a few adhesive bandages on his face would have a serious vision problem, whether male or female.

...from Buda-Pesth. (12)

Formerly independent Hungarian cities with long histories, Buda and Pest ("Pesth" is a phonetic spelling) were united in 1872. By Conan Doyle's time, the hyphen was rarely used, and today has disappeared entirely.

|

|

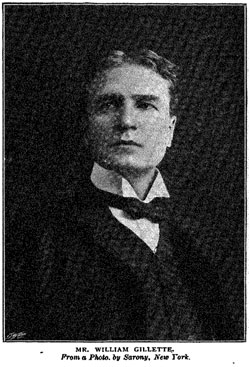

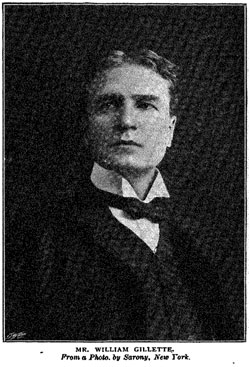

William Gillette, from The Strand Magazine, December 1901 |

During Conan Doyle’s first years at Undershaw, Sherlock Holmes was dead—lost, as far as the world knew, in a watery grave at the foot of Reichenbach Falls. Conan Doyle professed to be ecstatic at the prospect of never hearing of Holmes again, but, privately, perhaps he missed his creation, whose popularity had paid for Undershaw’s construction. A few years after writing “The Final Problem,” Conan Doyle started work on a Sherlock Holmes play that ended up in a desk drawer for a while before he offered it to an American promoter. Enter William Gillette.

American actor William Gillette (1853-1937) made a career out of playing brooding, complicated heroes, but the crowning role of his career was Sherlock Holmes. A shrewd judge of popular opinion, Gillette was a pioneer in creating some of the stage effects that became a staple of melodrama. By rewriting Conan Doyle’s play, Gillette made a vehicle that incorporated elements of several Holmes stories, but made Holmes himself a more conventional hero. In Gillette’s Sherlock Holmes, Moriarty appeared, guns were drawn on stage, and—yes, there was a heroine. The critics hated it, but the public, predictably, didn’t.

Conan Doyle thought that Gillette made a splendid Holmes, and artist Frederic Dorr Steele, an American illustrator of the Holmesian canon for Colliers, used Gillette as a model for Holmes. “It is not enough to say that William Gillette resembles Sherlock Holmes,” Orson Welles is supposed to have said. “Sherlock Holmes looks exactly like William Gillette.”

(More in the next issue….)

|