![]()

NOTES ON ISSUE 1: GLOSSARY

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was

the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it

was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of

Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had

everything before us, we had nothing before us…. [I]n short, the period was so

far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on

its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of

comparison only.

The period invoked by the opening chapter of A

Tale of Two Cities is the late 18th century – specifically (as we learn a

little later on) 1775; and Dickens’ “best of times” and “worst of times”

initiates a theme that helps prepare us for one of the major causes of the

French Revolution – the coexistence of opposed extremes (such as the coexistence

of immense wealth and immense poverty in France) in the pre-revolutionary

period.

The “season of Light,” coexisting with the “season of

Darkness,” invokes another irony of the period. Though the “Enlightenment”

(usually associated with the move from the superstitious world view of the

Middle Ages to the rationalism of 18th-century philosophy and science) may be

applied to aspects of various historical periods, the word itself became part of

European lexicons in the 18th century (in French, the word is

“Lumières”) (Roberts 268). If, however, the “Enlightenment” was a

period of reason, rationality, science, etc., it was likewise a period of

pseudo-science and new kinds of superstition. As one history of the period puts

it, “The eighteenth century was the century of mesmerism as well as of

inoculation; the cautious rationalism and theism of the early freemasons

ramified in a few decades into the luxuriant dottiness of mystical and occult

masonry” (Roberts 270). Thus the period in which the novel opens is a period

both of Light and Darkness – a period of contrasts.

The “present period” of the novel is of course 1859, when

A Tale of Two Cities first began serial publication. This period is

introduced as “so far like” 1775 perhaps because of the persistence of

contrasting extremes: In the 19th century, England led the Industrial Revolution

(for which the ground was laid by 18th-century developments like the steam

engine); yet unprecedented scientific, technological, and industrial progress

coexisted with the vogue of “spirit rappers,” mediums, phrenologists, and so

forth. Dickens makes reference to such phenomena in the opening chapter when he

notes that “Spiritual revelations were conceded to England at that favoured

period, as at this” (Ch.1).

There were a king with a large jaw and a

queen with a plain face, on the throne of England; there were a king with a

large jaw and a queen with a fair face, on the throne of France.

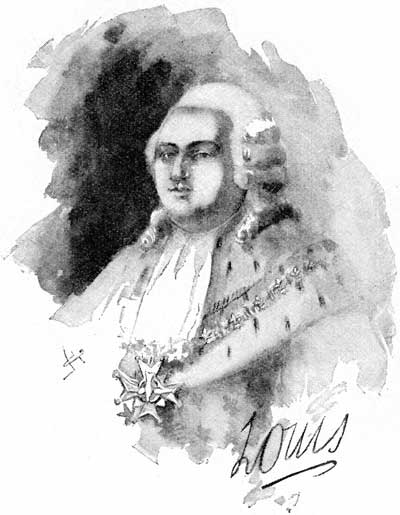

In

1775 (the year in which the story of A Tale of Two Cities begins), the

King and Queen of France were Louis XVI (r. 1774-93) and his consort,

Marie-Antoinette. In England, George III (r. 1760-1820) and his queen, Charlotte

Sophia, were the ruling couple.

These illustrations of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette,

taken from the Artist’s Edition of Carlyle’s French Revolution (1893),

show us the “king with a large jaw” and the “queen with fair face” of

France.

Since Dickens would probably have known George III’s profile from coins (Sanders 23), we are here including an illustration of the English “king with a large jaw” from an engraving – “A New Collection of ENGLISH COINS from Henry IV to George III, Accurately taken from the Originals” – from Thornton’s New, Complete, and Universal History, Description, and Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster [&c.] (1784). Dickens was born in 1812, and though George III was nominally king until 1820, his increasing mental instability necessitated the transfer of power to his son, who acted as Prince Regent from 1810 until George III’s death (at which point the Regent became George IV). It is therefore probable that, although Dickens was nearly eight years old before George III died, he would have known the monarch mainly from images on coins.

These illustrations of George III and his queen, Charlotte

Sophia, are taken from Holt’s The Public and Domestic Life of His Late Most

Gracious Majesty, George the Third (1820). They offer more

conventional portraits of the king “with a large jaw” and the “queen with a

plain face.”

Mrs. Southcott had recently attained her

five-and-twentieth blessed birthday, of whom a prophetic private in the Life

Guards had heralded the sublime appearance by announcing that arrangements were

made for the swallowing up of London and Westminster.

Joanna

Southcott was indeed 25 years old in 1775, though not yet known for the alleged

oracular powers that eventually made her famous. The Dictionary of National

Biography gives this account of

SOUTHCOTT, JOANNA (1750-1814), fanatic, daughter of William Southcott … by his second wife Hannah, was born at Gittisham, Devonshire, in April, 1750, and baptized on 6 June 1750 at Ottery St. Mary, Devonshire. Her father was a small farmer, and as a girl she did dairy work. Her first love affair was with Noah Bishop, a farmer’s son at Sidmouth, where her brother Joseph lived. After her mother’s death, an event which confirmed her in strong religious impressions (her father thought her too religious), she went out to service, her first place being as shop-girl at Honiton, where she rejected several suitors. For a short time she was a domestic in the family of a country squire, but was dismissed because a footman, whose attentions she had spurned, affirmed that she was “growing mad”; she claims that her removal had been divinely intimated to her. She next got employment at Exeter, living for many years in various families, as domestic and assistant in the upholstery business. Her character was blameless and her service faithful. She attended church, usually the cathedral, twice every Sunday, and was a communicant; she also regularly frequented Wesleyan services before and after church hours. Though pressed to join the Methodist society, she did not do so till Christmas 1791, and then “by divine command.” (278)

In 1775, then, Joanna Southcott was not yet known as the prophetess that she became thereafter (though her story would have been well known to Dickens’ readers in 1859). She began to write prophecies in 1792, and – when they were disbelieved – “adopted the plan of sealing up her writings, to be opened when the predicted events had matured” (DNB 278). In 1801, she began to publish her works, gained followers, and underwent several “trials” of her predictions; in 1813, at the age of sixty-three, it was announced that she was pregnant with the second Christ, Shiloh:

Of nine medical men consulted on the case, six admitted that the symptoms would, in a younger woman, indicate approaching maternity. The excitement of Joanna’s followers knew no bounds. In September a crib costing £200 was made to order by Seddons of Aldergate Street; £100 was spent in pap-spoons [feeding-spoons for the baby]; a bible was superbly bound as a birthday present. The “Morning Chronicle,” which had inserted an advertisement for “a large furnished house” for a public accouchement, announced next day that “a great personage” had offered “the Temple of Peace in the Green Park.” (279)

Southcott herself apparently realized that she was dying,

returned the parcels intended for Shiloh, and requested that an autopsy be

performed four days after her death. She died on December 27, 1814, and the

medical examination made in compliance with her request showed “no functional

disorder or organic disease,” suggesting rather that “‘all the mischief lay’ in

the brain, which was not examined, owing to the high state of putrefaction”

(279).

The “prophetic private” in the Life Guards to whom Dickens refers

predicted – in 1750, the year of Joanna Southcott’s birth – that London and

Westminster would be destroyed. Dickens associates the date of the

life-guardsman’s prediction with the date of Joanna Southcott’s nativity,

facetiously suggesting that the guardsman’s prophesy was in fact prophetic, not

of the swallowing of London and Westminster, but of the birth of another

prophet. Though rapidly confined to Bedlam (the London insane asylum) for his

remarks, the life-guardsman’s prophecy instigated panic in London – “The London

churches were crowded, and the Bishop of London called his flock to repentance

in a pastoral letter of which some 10,000 copies are said to have been sold”

(Sanders 29). Dickens may be conflating the 1750 prophesy of the life-guardsman

with a similar 1775 prophesy – not originated by a life-guardsman – to the

effect that “on [February 1, 1775] the people about Deptford and Greenwich had

been alarmed with the reveries of a crazy prophet, who had predicted that on

this day these towns were to be swallowed up by an earthquake” (Annual

Register for the Year 1775 88). (Deptford and Greenwich are

villages about 4.5 and 5 miles east of the center of London [Harper, “The Road

to Dover”], now absorbed into the general metropolitan area.)

Even

the Cock-lane ghost had been laid only a round dozen years, after rapping out

its messages, as the spirits of this very year last past (supernaturally

deficient in originality) rapped out theirs.

The Cock-lane ghost

ostensibly began to disturb the residents of a house in Cock Lane, West

Smithfield (in London) in the first few months of 1762 (and had thus been laid

to rest slightly more than a dozen years in 1775). Its knockings and scratchings

were supposed to derive from the spirit of woman who had been murdered and was

buried nearby. Though the phenomenon was ultimately exposed as a fraud, it

attracted considerable popular interest; and when Mr. Parsons, the father of the

12-year-old girl first disturbed by the “Ghost,” was sent to prison for a year

and forced to stand in the pillory for perpetrating the sham, Londoners

collected a subscription for his well-being (Sanders 30).

Dickens’ reference to the “spirits of this very year last past” refers to the “spirit rappers” of the late 1850s (which announced themselves chiefly by shaking tables and rapping out messages). Dickens satirized spirit mediums – people who claimed to be in communication with the dead – in his magazine Household Words. “Spirits Over the Water,” by James Payn, appeared in the June 5, 1858 number of Household Words, reporting the vogue of spirit-rappers and mediums in America; and Dickens himself, in the February 20, 1858 number, penned an article entitled “Well-Authenticated Rappings.” In this piece, a spirit by the name of “Port!” inaugurates the day after Christmas by rapping on the writer’s (Dickens’) head, and a spirit named “Pork Pie” follows up the “previous remarkable visitation” by instigating orchestral maneuvers “resembling a melodious heart-burn” (218). These notices, appearing in 1858 – the year before A Tale of Two Cities commenced publication – report the popularity of the “spirits of this very year last past”; yet Dickens had been making fun of spirit rappers for most of the preceding decade. In an 1853 article called “The Spirit Business,” Dickens reviewed a series of publications on spirit-rapping and mediums in America, giving, among other things, excerpts of spirit communications such as the following:

FROM AN ANONYMOUS SPIRIT, PRESUMED TO BE OF THE QUAKER PERSUASION[:] “Dear John, it is a pleasure to address thee now and then, after a lapse of many years. This new mode of conversing is no less interesting to thy mother than to thee. It greatly adds to the enjoyment and happiness of thy friends here to see thee happy, looking forward with composure to the change from one sphere to another.” (218)

He also transcribes

…a few individual cases of spiritual manifestation: – There was a horrible medium down in Philadelphia, who recorded of herself, “Whenever I am passive, day or night, my hand writes.” This appalling author came out under the following circumstances: – “A pencil and paper were lying on the table. The pencil came into my hand; my fingers were clenched on it! An unseen iron grasp compressed the tendons in my arm – my hand was flung violently forward on the paper, and I wrote meaning sentences without any intention or knowing what they were to be.” The same prolific person presently inquires, “Is this insanity?” To which we take the liberty of replying, that we rather think it is. (219)

Further, another unwilling medium attended a gathering and

…put forth a strong effort of the will to induce a passiveness in my nervous system; and, in order that I might not be deceived as to my success, resigned myself to sleep…. I suppose I was unconscious for thirty minutes” [italics and ellipses are Dickens’]. After[wards] this seer had a vision of stalks and leaves, “a large species of fruit, somewhat resembling a pine-apple,” and “a nebulous column, somewhat resembling the milky way,” which nothing but spirits could account for, and from which nothing but soda-water, or time, is likely to have recovered him. We believe this kind of manifestation is usually followed by a severe headache next morning, attended by some degree of thirst. (219)

Mere messages in the earthly order of events had lately

come to the English Crown and People, from a congress of British subjects in

America.

Between September 5 and October 26, 1774, the first

Continental Congress of England’s American colonies met in Philadelphia; it

presented a list of grievances to the English government in January of the

following year. This “message” from the “British subjects in America” preceded

the Declaration of Independence (1776) and the ensuing Revolutionary War

(Sanders 30; Maxwell 442; Roberts 345). The Annual Register of 1775

gives a long account of the Continental Congress’ meeting and the various

“messages” sent to the crown, including a

…declaration of rights, to which, they say, the English colonies of North-America are entitled, by the immutable laws of nature, the principles of the English constitution, and their several charters or compacts. In the first of these are life, liberty, and property, a right to the disposal of any of which, without their consent, they had never ceded to any sovereign power whatever. That their ancestors, at the time of their migration, were entitled to all the rights, liberties, and immunities, of free and natural born subjects; and that by such emigration, they neither forfeited, surrendered, nor lost, any of those rights. They then state, that the foundation of English liberty, and of all free government, is a right in the people to participate in their legislative council; and proceed to shew, that as the colonists are not, and, from various causes, cannot be represented in the British parliament, they are entitled to a free and exclusive power of legislation in their several provincial legislatures, where their right of representation can alone be preserved, in all cases of taxation and internal policy, subject only to the negative of their sovereign, in such manner as had been heretofore used and accustomed [etc.]. (25-6)

In addition to this declaration, the Continental Congress

“proceeded to frame a petition to his Majesty, a memorial to the people of Great

Britain, an address to the colonies in general,” etc., the “petition to his

majesty contain[ing] an enumeration of their grievances” (28). After giving a

protracted account of the assembly and communications of the Continental

Congress, stressing both its declarations of loyalty to the English and its

objections to the conduct of English rule, the Annual Register

concludes its entry with a general commendation: “[I]t must be acknowledged,

that the petition and addresses from the congress have been executed with

uncommon energy, address, and ability; and that considered abstractedly, with

respect to vigour of mind, strength of sentiment, and the language, at least of

patriotism, they would not have disgraced any assembly that ever existed” (36).

France, less favored … than her sister of the shield and trident,

rolled with exceeding smoothness down hill, making paper money and spending it.

France’s “sister of the shield and trident” is England, as the

nation is represented by “Britannia” – a female figure in armor with a trident

in one hand and a round shield (bearing the union jack) in the other:

BRITANNIA was the original name given by the Romans to their newly-conquered province that comprised what is now England and Wales (neighboring Ireland was known as Hibernia, Scotland was Caledonia, Germany was Germania, Brittany was Armorica and France was just plain Gaul). After the Romans left, the name gradually fell into disuse, but later, in the days of the Empire, it came to represent the spirit of Britain herself…. Roman coinage of the day featured the image of a woman in armor. This image was not used on coins again until the reign of King Charles II [in the 17th century]. Since 1672, Britannia has been anthropomorphised into a woman wearing a helmet, and carrying a shield and trident. It is a symbol that blends the concepts of empire, militarism and economics…. Britannia became a popular figure in 1707 when Scotland, Wales and England were finally united to form Great Britain [and] has continued to feature on British coins since her reintroduction, mostly on copper coins (penny and halfpenny) but occasionally on silver, and at present is to be seen on the 50p coin. (“Symbols of Britishness”)

Since the figure of Britannia was often found on the backs of pennies in the 1850s, and was the basic design for the flip side of all pennies from 1860 to 1970 (Clayton, “The Penny”), Dickens’ reference to England as France’s “sister of the shield and trident” makes use of a symbol of Englishness specifically associated with currency at the time A Tale of Two Cities appeared. Moreover, Britannia appeared on English coins, which retain a closer association to precious metals (and thus a gold or silver standard) than paper money, which France began to print in great quantities (and without sufficient reserves of gold to assure its value) in the years before the French Revolution. As Carlyle describes the period, peaceful but in serious financial decline –

Is it the healthy peace, or the ominous unhealthy, that rests on France, for these next Ten Years? Over which the Historian can pass lightly, without call to linger: for as yet events are not, much less performances. Time of sunniest stillness; – shall we call it, what all men thought it, the new Age of Gold? Call it at least, of Paper; which in many ways is the succedaneum of Gold. Bank-paper, wherewith you can still buy when there is no gold left; Book-paper, splendent with Theories, Philosophies, Sensibilities – beautiful art, not only revealing Thought, but also so beautifully hiding from us the want of Thought! Paper is made from the rags of things that did once exist; there are endless excellences in Paper. (25-6)

Carlyle, as Sanders points out in his Companion to A Tale

of Two Cities, “sees France’s problem as one of both moral and financial

bankruptcy” in this period. In the strictly financial sense, however, France’s

efforts since the early 17th century to retain a position of European prominence

and power had built up a national debt that a series of ministers under Louis

XVI (who was crowned in 1774) tried unsuccessfully to ameliorate (Roberts 349).

French assistance to America during the Revolutionary War only exacerbated this

condition, and, by the early 1780s, France was threatened – as Carlyle puts it –

with “the black horrors of NATIONAL BANKRUPTCY” (56).

…such humane

achievements as sentencing a youth to have his hands cut off, his tongue torn

out with pincers, and his body burned alive, because he had not kneeled down in

the rain to do honor to a dirty procession of monks which passed within his

view, at a distance of some fifty or sixty yards.

This passage refers

to the sentencing and execution of the Chevalier de la Barre in 1766. Accused of

acting disrespectfully to a religious procession – de la Barre had not removed

his hat when he passed within 30 yards of a procession bearing a crucifix, and

had allegedly spoken “irreverently of the Virgin Mary” and “sung bawdy songs”

(Sanders 31) – de la Barre was condemned at Amiens to undergo the punishments

described (to have his tongue cut out, his right hand cut off, and afterwards to

be burned alive – a punishment subsequently “softened” to decapitation prior to

burning).

Dickens, who owned a copy of Voltaire’s Oeuvres Complètes (complete works), was probably familiar with the story from the Relation de la mort du chevalier de la Barre, in which Voltaire describes the circumstances of the accusation, the “evidence” gathered against de la Barre, and his ultimate sentencing and execution: The Chevalier de la Barre, a young soldier, was staying with his aunt, an abbess, when she became the object of romantic attentions from a man named Belleval. Belleval, rejected, attempted to ruin the abbess financially, and, when her nephew came to her aid, attempted to ruin him by spreading the rumor of his disregard of a passing religious procession. The disturbance created by these allegations coincided with the destruction of a crucifix hanging on a bridge, and Belleval alleged that de la Barre was responsible. Ultimately, the maneuvers of Belleval and the public indignation they occasioned led to de la Barre’s denunciation on the following allegations:

On 13 August 1765, six witnesses testified that they saw three young men pass within thirty paces of a religious procession, that la Barre and d’Etallonde did not take off their hats, and that Moisnel held his hat under his arm.

In an additional piece of information, Elisabeth Lacrivel testified that she had heard from one of her cousins that this cousin had heard the chevalier de la Barre say that he had not taken off his hat.

On 26 September a commoner called Ursule Gondalier testified that she had hear it said that la Barre, when he saw a plaster figure of Saint Nicholas at the house of the convent’s portress, Sister Marie, had asked her if she had bought the figure to have a man in her home.

A man called Bauvalet testified that the chevalier de la Barre had uttered an impious word when speaking of the Virgin Mary.

Claude, known as Sélincourt, gave uncorroborated evidence that the accused told him God’s commandments were the work of priests; but, confronted with this, the accused maintained that Sélincourt was a liar and that they were only speaking about the commandments of the Church.

A man called Héquet, also an uncorroborated witness, testified that the accused told him he could not understand how one could worship an image of God. The accused, when questioned about this, said he had been speaking about Egyptians.

Nicholas Lavallée testified that he had heard the chevalier de la Barre sing two blasphemous guardroom songs. The accused admitted that one day when he was drunk he had sung them with d’Etallonde, without knowing what he was saying: in truth Mary Magdalene is referred to as a whore in one song, but she had led a loose life before her conversion. He agreed that he had recited Piron’s Ode to Priapus.

The said Héquet also testified that he had seen the chevalier genuflect in front of books entitled Thérèse Philosophe, the Tourière des Carmelites and the Portier des Chartreux [well-known works of pornography]. He did not mention any other book, but, when questioned about this and asked to verify it, he said he was not sure if it was la Barre who had genuflected. [etc.] (Voltaire 142)

As Voltaire points out, the precedent for de la Barre’s

punishment was a sentence of 1682 whereby two women and two priests, who had

“committed imaginary acts of sorcery and real acts of poisoning their victims”

(145), had been put to death as “profaners and poisoners.” De la Barre, on the

scaffold, said that he “never thought that a gentleman could be put to death for

so little” (147). Voltaire told his story in the hopes of reforming the social

and legal circumstances that allowed it.

…rooted in the woods of

France and Norway, there were growing trees … marked by the Woodman,

Fate…

Dickens’ figure of “the Woodman, Fate,” may have been partly

suggested by a passage in his chief historical source, Carlyle’s French

Revolution. Describing the imperceptibility of the growth and termination

of great things, Carlyle writes,

The oak grows silently, in the forest, a thousand years; only in the thousandth year, when the woodman arrives with his axe, is there heard an echoing through the solitudes; and the oak announces itself when, with far-sounding crash, it falls. (24)

According to Sanders, the “best lengths of pine” used for

building were imported from Norway (31).

…to make a certain moveable

framework with a sack and a knife in it, terrible in history.

The

“moveable framework with a sack and knife in it” is the guillotine, named for

its inventor, Joseph Ignace Guillotin (1738-1814), who was active in French

politics before and during the French Revolution. A member of the Constitutional

Assembly prior to the Revolution, Guillotin proposed the use of his machine in

1785; it was frequently though erroneously thought, in Dickens’ time, that

Guillotin had been executed by his own instrument. (Though Guillotin was

imprisoned during the Reign of Terror, he was not guillotined [Sanders 32].)

Ironically, the device Guillotin invented for executions was intended to

be more humane than the standard means of execution, instantly and painlessly

severing the head from the neck. The first models of the machine were created by

Dr. Antoine Louis of the French College of Surgeons, and were thus named

“louison” and “louisette” after him; the later and more famous models were named

after their original inventor (Guillotin). The mechanized executions made

possible by the guillotine have occasionally been viewed as “symbolic of the

birth of the modern state” (Murphy 224); indeed, use of the guillotine was not

discontinued in France until 1981, and the last person to be executed by means

of the guillotine died in 1977 (Murphy 223-4). The appearance of the guillotine

is famous – a tall wooden framework with a blade pulled to the top (which drops

down and severs a head placed in the bottom of the frame), and a sack to catch

the heads.

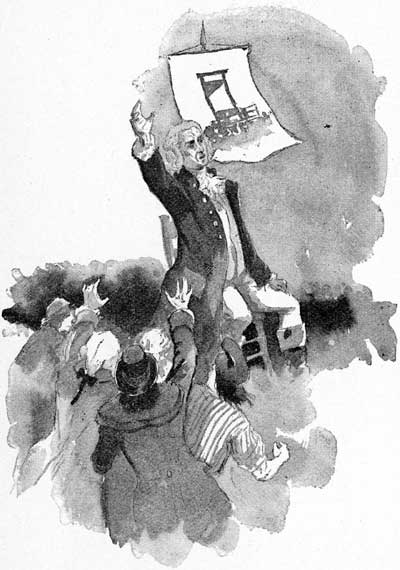

This illustration of Doctor Guillotin, with a model drawing of

his machine, is taken from the Artist’s Edition (1893) of Carlyle’s French

Revolution.

…set apart to be his tumbrils of the

Revolution.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a

tumbril is a little cart. In the French Revolution, these carts – originally

farm-carts – were used to transport victims of the Revolution from their trials

at the Conciergerie to the guillotine (Sanders 32). Though people were

guillotined in various parts of Paris during the Revolution, the most famous

site of the guillotine was in the Place de la Révolution – called the Place de

Louis XV previous to the Revolution, and now called the Place de la Concorde.

In England… [d]aring burglaries by armed men, and highway robberies,

took place in the capital itself every night, families were publicly cautioned

not to go out of town without removing their furniture to upholsterers’

warehouses for security…

Dickens’ gloss of criminal activity in 1775

is based on events recorded in the Annual Register, or a View of the History, Politics and

Literature for the Year 1775. (Dickens possessed Annual Registers for the period ranging from

1748-1860 [Sanders 24].)

Many passages from the Annual Register

seem to suggest that England was overrun with burglars and highwaymen in 1775.

The simplest and most expressive are perhaps the accounts of convictions and

executions:

The sessions ended at the Old Bailey [Old Bailey is the London street in which the Sessions House – where prisoner were tried – was located], when three criminals for house-breaking, one for highway robbery, and two for returning from transportation [i.e. a sentence of deportation to the colonies], received sentence of death; and, on the 21st of April, one of those condemned for house-breaking, and one of those condemned for returning from transportation, were executed at Tyburn. At the same sessions 31 were sentenced to be transported for 7 years, 6 to be branded in the hand, 2 of whom are to be imprisoned 6 months, 13 to be whipt, and 30 delivered on proclamation. (Feb. 21, 1775; 92)

Ended the sessions at the Old Bailey, when the court passed sentence of death on two criminals, for highway robbery; nine, for house-breaking; one, for stealing cattle; one, for horse-stealing; and one, for stealing from a person, to whom he was clerk, two warrants, one for £213, the other for £1561 4s. for which he had received the money; and, on the 7th of June, five of the house-breakers, and the clerk for stealing the warrants, were executed at Tyburn. (May 2, 1775; 115)

The sessions ended at the Old Bailey, when fourteen convicts received sentence for death, viz. the two unfortunate brothers, Robert and Daniel Perreau, for forgery; four, for street, field, and highway robberies; three for house-breaking, and house robberies; one, for theft; one, for firing a pistol at Walter Butler, one of the patrol, near the Foundling Hospital, and wounding him in the neck; two, for coining; and one, for horse-stealing; one received sentence for transportation for fourteen years; sixteen, sentence of transportation for seven years; and nine convicted of coining halfpence, were branded in the hand, and sentenced to suffer an imprisonment in Newgate for twelve months…. And on the 19th of July following, seven of the above capital convicts were executed at Tyburn; among whom were the two coiners. (June 7, 1775, 130)

From these and further accounts of convictions and executions in the Annual Register, one gets the impression, just as Dickens apparently did, that England in 1775 was not only overrun with highwaymen and house-breakers, but specialized in a particularly barbarous system of punishment (hangings, brandings, etc.). Indeed, the Annual Register is full of stories of “daring burglaries” and other fantastic crimes. For example, an entry from 1775 describes how

A well-dressed man knocked at a milliner’s in Pallmall, under pretence of wanting some ruffles; and being let in by the mistress, immediately locked the door on the inside, pulled out a pistol, and with horrid imprecations threatened to destroy her if she spoke a word; he then tied a bandage over her eyes, bound her, and stripped the shop of nearly £80 worth of lace and linen. (83)

Another entry describes the perils of apprehending thieves:

Two serjeants in the Surry militia, and two other men, in coming from Kingston toward London, meeting a fish-man of about 70, with part of a field-gate on his back, asked him if he came honestly by it; and, on his seeming confused, one of them attempted to secure him; but, before he could effect it, the fellow pulled out a large knife, and stabbed him in the breast, who immediately cried out he had received his death’s wound; then, the others endeavoring to secure him, he stabbed a second in the belly, a third in the arm, and the fourth in the groin. At length, several people coming up, he was overpowered, and conducted to the New Gaol. One of them died the next morning, and two of the others soon after. Of such fatal efficacy is any weapon in desperate hands against naked, though far superior strength and numbers!

…the highwayman in the dark was a City tradesman in the

light, and being recognized and challenged by his fellow-tradesman whom he

stopped in his character of ‘the Captain,’ gallantly shot him through the head

and rode away….

As Sanders notes in his Companion to A Tale of

Two Cities, Dickens gets this story slightly wrong (32). The account in the

Annual Register of 1775 describes the events of January 4, 1775

as follows:

Mr. Brower, a print-cutter, near Aldersgate-Street, was attacked on the road to Enfield by a single highwayman, whom he recollected to be a tradesman in the city; he accordingly called him by his name, when the robber shot himself through the head. (82)

The part of London called “the City” is the

commercial center of the metropolis. Baedeker’s handbook to London and Its

Environs (1908) describes this region as follows: “The CITY and the EAST

END, consisting of that part of London which lies to the E[ast] of the Temple,

form the commercial and money-making quarter of the Metropolis. It embraces the

Port, the Docks, the Custom House, the Bank, the Exchange, … and the Cathedral

of St. Paul’s, towering over them all…. On the W[est] verge of the City are

Chancery Lane and the Inns of Court, the headquarters of

barristers, solicitors and law-stationers” (xxix).

The area described is

visible on this portion of Thornton’s map of London (1784). Chancery Lane is

just above Temple Bar at the left side of the map; the Thames (with Docks and

Ports) is at the bottom; the Bank and the Exchange are marked (but not labeled)

to the left of Threadneedle Street and above Cornhill (the crease in the map

runs through them); and St. Paul’s is near the middle.

“The Captain” was apparently a stock name or

frequent pseudonym for highwaymen, especially in the 18th century (Sanders

32).

…the mail was waylaid by seven robbers, and the guard shot three

dead, and then got shot dead himself by the other four, ‘in consequence of the

failure of his ammunition’: after which the mail was robbed in

peace…

Dickens is here glossing the events of December 5, 1775, as

recorded in the Annual Register of that year. The notice in the Annual

Register reports the story as follows:

The Norwich stage was this morning attacked, in Epping forest, by seven highwaymen, three of whom were shot dead by the guard; but his ammunition failing, he was shot dead himself, and the coach robbed by the survivors.

Though Dickens identifies the coach attacked by highwaymen as

“the mail,” the incident (in 1775) precedes the advent of mail-coaches in

England (the first of which began to transport mail in 1784 [Harper 40]). The

vehicle attacked was actually the “Norwich stage” – a stagecoach on the Norwich

road. (Stage-coaches were conveyances traveling in “stages,” which the

OED defines as “division[s] of a journey or process,” or “[a]s much of

a journey as is performed without stopping for rest, a change of horses, etc.;

each of the several portions into which a road is divided for coaching or

posting purposes; the distance traveled between two places of rest on a road.”)

…the Lord Mayor of London, was made to stand and deliver on Turnham

Green, by one highwayman, who despoiled the illustrious creature in sight of all

his retinue…

Here, Dickens mistakes events of 1776 for those of 1775

(Sanders 32). The Annual Register of 1776 records that on September 6,

The lord-mayor of London was robbed near Turnham-Green, in his chaise and four, in sight of all his retinue, by a single highwayman, who swore he would shoot the first man that made resistance, or offered violence. (177).

The Lord Mayor of London is the mayor of the capital city, though distinct from the Mayor of London, an elected politician; the title “Lord Mayor” was originally reserved for the mayors only of London, York, and Dublin, but has since been extended to the mayors of other metropolises, such as Liverpool, Birmingham, Sheffield, etc. (OED). The first Lord Mayor was appointed in 1189; in 1775, the Lord Mayor was John Sawbridge; and in 1776, Sir Thomas Hallifax (Lord Mayor of London, Wikipedia). The appointment of the Lord Mayor is still attended with considerable pomp: On the Lord Mayor’s Day, November 9, the Lord Mayor goes in procession from London to Westminster, where he receives the assent of the monarch to his appointment (OED).

Turnham Green, to which the London Underground may now be

taken, is in Chiswick, west of London.

…prisoners in London goals

fought battles with their turnkeys, and the majesty of the law fired

blunderbusses in among them, loaded with rounds of shot and

ball…

Dickens is referring here to the events of March 14, 1775,

recorded in the Annual Register as follows:

Robert Rous, one of the turnkeys of the New Gaol, Southwark, seeing a prisoner, who was committed there for different highway robberies, with rags tied round his fetters, ordered him to take them off; and, on his refusing to do it, he immediately cut them off; when, finding both his irons sawed through, he [the turnkey] secured him [the prisoner], and then sent up two of his assistants to overlook a great number of prisoners who were in the strong room. Upon this the prisoners immediately secured one of the assistants in the room, and all fell on him with their irons, which they had knocked off. Rous hearing of it, went up with a horse-pistol, and extricated his fellow turnkey from their fury, and then locked the door. All the turnkeys, as well as constables, now surrounded the door and the yard; and the prisoners fired several pistols loaded with powder and ball at two of the constables; when, the balls going through their hats, and the outrages continuing, one of the constables, who had a blunderbuss loaded with shot, fired through the iron grates at the window, and dangerously wounded one fellow committed for a burglary in the Mint. At length a party of soldiers, which had been sent for to the Tower [of London], being arrived, and having loaded their muskets, the room was opened, and the prisoners were all secured and yoked, and 21 of them chained down to the floor in the condemned room. Some of the people belonging to the prison were wounded. (98)

“Blunderbusses” are a kind of gun, described in Fairholt’s

Costume in England, A History of Dress (1860) as “Short hand-guns of

wide bore.” The odd name, “blunderbuss,” attracts attention, and Fairholt quotes

a 17th-century opinion that “I do believe the word is corrupted; for I guess it

is a German term, and should be donderbucks, and that is ‘thundering

guns,’ donder signifying thunder, and bucks a gun” (370). The OED gives

a similar, but more elaborate etymology: Describing “blunderbuss” as an

adaptation of the Dutch word “donderbus” (“donder” meaning “thunder” and “bus”

meaning gun or, originally, box or tube), the OED suggests that

“donder” was “perverted in form” to blunder, perhaps intentionally as “some

allusion to its blind or random firing.” The OED’s definition of

blunderbuss is “[a] short gun with a large bore, firing many balls or slugs, and

capable of doing execution within a limited range without exact aim (now

superseded, in civilized countries, by other fire-arms).” Date charts and

examples of the use of the word “blunderbuss” suggest that this kind of gun was

most frequently in use between the 17th and mid-19th centuries.

“Shot and

ball” refers to the ammunition with which blunderbusses were loaded. According

to the OED, “shot” and “ball,” in their association with firearms,

originally referred to the missiles appropriate to various kinds of large, early

weaponry. “Ball” originally referred to the projectile missiles of catapults and

crossbows, and later of cannons, muskets, etc; “shot” was usually associated

with cannon or other artillery in which these projectiles were propelled “by

force of an explosion.” In later usage, shot and ball both came to refer to the

smaller discharges of hand-held guns.

…thieves snipped off diamond

crosses from the necks of noble lords at Court drawing-rooms; musketeers went

into St. Giles’s, to search for contraband goods, and the mob fired on the

musketeers, and the musketeers fired on the mob…

According to the

Annual Register, on June 22, 1775,

Being the day appointed for keeping the anniversary of his Majesty’s birth-day, who entered into the 38th year of his age on the 4th instant, it was celebrated with the usual joy and splendour. Lord Stormonth’s St. Andrew’s cross, set round with diamonds, and appended to his ribbon of the order of the Thistle, was cut from it, at court, by some sharpers, who made off with it undiscovered. It was worth several hundred pounds. (132)

And on September 27, 1775,

In consequence of an information given of a considerable quantity of contraband goods being lodged at a house in Buckridge-street, St. Giles’s, Mr. Phillips, a Custom-house officer, attended by a number of peace-officers, and a file of musqueteers from the Savoy, went in search of the goods; and, in one room where they got entrance, they found a bag and eight pounds of tea, which were lodged in the Custom-house. Immediately after the officers and guards had left the house, and got into the street, they were fired at several times from the mob, and pelted with brick-bats, &c. but no person received the least hurt from this outrage but Mr. Phillips, who had his nose cut by a piece of glass bottle. Not content with this, the mob followed them; and, after pelting, fired at them; on which the guard returned, and discharged their musquets among the mob, when some, it is said, were killed and wounded. One of the ringleaders of the gang was taken before the magistrates of Litchfield-street, who committed him to Newgate. (163)

In this and other entries in the Annual Register, a

“mob” appears to materialize out of nowhere, suggesting that chaos threatened,

at any moment, to break out in the London streets. In fact, mobs were somewhat

frequent in 18th-century London, but were usually motivated by some kind of

social or political protest (Johnson 31-2).

In the midst of them, the

hangman … was in constant requisition; now, stringing up long rows of

miscellaneous criminals; now, hanging a housebreaker on Saturday who had been

taken on Tuesday; now, burning people in the hand at Newgate by the dozen, and

now burning pamphlets at the door of Westminster Hall; today, taking the life of

an atrocious murderer, and to-morrow of a wretched pilferer who had robbed a

farmer’s boy of sixpence.

According to entries in the Annual

Register of 1775, the London executioner was indeed responsible for the

various punishments enumerated here – hanging housebreakers, burning thieves in

the hand, and burning pamphlets outside Westminster Hall. An account of January

and February 1775 describes a series of punishments handed down at the sessions

in which criminal trials were heard, including the sentence of a thief of a

farmer’s boy’s sixpence:

The sessions were ended at the Old Bailey; when the court passed sentence of death on eight convicts; sentence of transportation for seven years, on forty-three; and for 14 years, on three more. Three were ordered to be branded in the hand, and four to be privately whipt. And on the 15th of February, four of the capital convicts were executed at Tyburn. The fifth was pardoned on condition of transport for his natural life. One of those who suffered was for robbing a farmer’s boy of six-pence. (83)

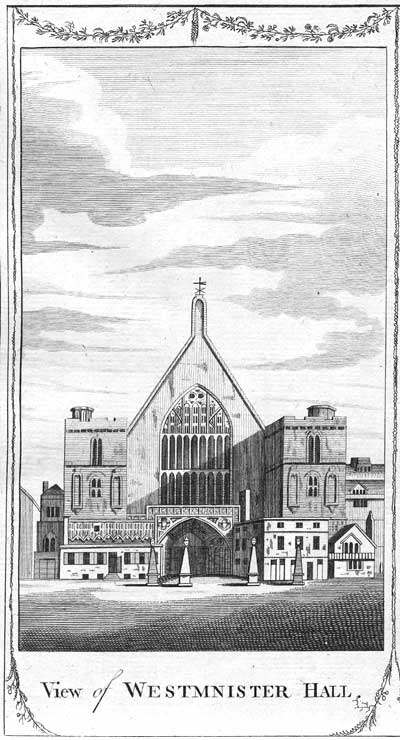

The duty of burning pamphlets outside Westminster Hall also devolved upon the hangman, apparently as a way of performing, publicly, the condemnation of seditious tracts. The Annual Register of 1775 describes this process in application to pamphlets defending the cause of the American colonies against England:

Lord Effingham complained in the House of Lords of the licentiousness of the press, and produced a pamphlet entitled, “The Present Crisis with Respect to America Considered,” published by T. Becket, which his Lordship declared to be a most daring insult on the king: and moved, that the house would come to resolutions to the following effect:

That the said pamphlet is a false, malicious, and dangerous libel…. That one of the said pamphlets be burnt by the hands of the common hangman in Old Palace-yard; and another, at the Royal Exchange.

That these resolutions be communicated to the House of Commons at a conference, and that the concurrence of that house be desired. Which resolutions being read, were unanimously agreed to…. A second conference now ensued, arising from a complaint of the Earl of Radnor in the Upper House, and of Lord Chewton in the Lower House, against a periodical paper, called The Crisis, No. 3 published for T. Shaw, &c. In the Lower House, the paper in question had been voted a false, malicious, and seditious libel; in the Upper House, the word treasonable was added; but, upon re-considering the matter, that was omitted: but it was, like the other, unanimously ordered to be burned by the hands of the common hangman…. In obedience to the above orders, these pieces were burnt, on the 6th of March following, by the common hangman, at Westminster-hall gate. (94-5)

Westminster Hall is an old building – erected in 1397 under Richard II – which still stands. It is located across from Westminster Abbey, on the side of the houses of Parliament facing away from the Thames (the houses of Parliament are much newer, having been rebuilt in the 19th century). It was used as a royal banqueting and coronation hall (a wedding banquet was given there for George III and his queen on September 22, 1761 [Gaspey 137]), and peers accused of treason were frequently tried there (e.g. Guy Fawkes [Woodley 192]). In the 18th century, Westminster Hall contained the courts of Chancery, King’s-bench, and Common Pleas (Harrison 517-8); it is now devoted to no specific purpose, but is sometimes used for state occasions (Woodley 192).

Thornton’s New, Complete, and Universal History, Description, and Survey of … London (1784) furnishes us with an illustration of Westminster Hall as it appeared in the late 18th century.

Old-Palace Yard (identified by the Annual Register as

one of the locations in which the “common hangman” was to burn seditious

pamphlets) was the site of the original Westminster Hall, a banqueting-house

constructed by William Rufus, which Richard II replaced with the Hall that still

stands.

…carrying their divine rights with a high hand.

According to the OED, the “divine right of kings” is the

monarchical doctrine that “kings derive their power from God alone, unlimited by

any rights on the part of their subjects.”

The Dover road that lay …

beyond the Dover mail, as it lumbered up Shooter’s Hill.

The Dover

road, 70.75 miles long, ran from London Bridge (on the Surrey side of the Thames

River) to Dover (Harper, “The Road to Dover”). Shooter’s Hill, 8.25 miles along

the Dover Road from London Bridge, is an eminence from which the city of London

could be seen during the daytime; in the 18th century it was known for a mineral

spring where Queen Anne herself (r. 1702-1714) was said to take the waters. At

night, however, it was dangerous. According to Charles Harper, in his account of

The Dover Road (1922),

Shooter’s Hill was not always a place whereon one could rest in safety. Indeed, it bore for long years a particularly bad name as being the lurking-place of ferocious footpads, cutpurses, highwaymen, cut-throats, and gentry of allied professions who rushed out from [the] leafy coverts and took liberal toll from wayfarers…. So long ago as 1767 [eight years before the date of the mail-coach’s passage over Shooter’s Hill in A Tale of Two Cities] a project was set afoot for building a town on the summit of Shooter’s Hill, but it came to nothing, which is not at all strange when one considers how constantly the dwellers there would have been obliged to run the gauntlet of the gentlemen whom Americans happily call “road-agents.” And here is a sample of what would happen now and again, taken … from the … columns of a London paper, under date of 1773. “On Sunday night,” we read, “about ten o’clock, Colonel Craig and his servant were attacked near Shooter’s Hill by two highwaymen, well mounted, who, on the colonel’s declaring he would not be robbed, immediately fired and shot the servant’s horse in the shoulder. On this the footman discharged a pistol, and the assailants rode off with great precipitation.” That they rode off with nothing else shows how effectually the colonel and his servant, by firmly grasping the nettle danger, plucked the flower safety. (36-7)

Harper goes on to excerpt the accounts of Shooter’s Hill found

in Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities and Byron’s Don Juan (1821). In

the latter, Don Juan finds himself “greeted” by highwaymen, which he takes for

an English custom of salutation. Of Dickens’ novel, Harper says he has but one

criticism to make – “There was no Dover Mail coach in 1775, for the earliest of

all mail coaches, that between Bristol and London, was not established before

1784. The mails until then were carried by post-boys on horse-back” (40). Thus,

though guilty of a minor anachronism on this point, Dickens combines a common

conveyance employed in his own time (passengers frequently booked places on

mail-coaches, which traveled regularly between set points) with the dangers of

the Dover Road in the late 18th century.

…with the mutinous intent of

taking it [the coach] back to Blackheath.

Blackheath, five miles from

the origin of the Dover Road, is the station on the road most immediately

preceding Shooter’s Hill, about 3.25 miles back in the direction of London

(Harper, “The Road to Dover”). Harper, in The Dover Road, describes

Blackheath as still, in 1922,

one of the finest suburbs of London…. Strange to say, it has not been spoiled, and though thickly surrounded with houses, remains as breezy and healthful as ever; perhaps, indeed, since highwayman and footpad have disappeared, and now that duels are unknown, Blackheath may be regarded as even more healthy a spot than it was a hundred years ago.

The air which gave Black Heath its original name [the Blue Guide notes that Blackheath still seems “well named” on a “cold, cloudy day” (404)], and nipped the ears and made red the noses of the “outsides” [passengers who rode on the outside of traveling coaches] who journeyed across it on their way to Dover in the winter months, is healthful and bracing, and is not so bleak as balmy in the days of June, when the sun shines brilliantly, and makes a generous heat to radiate from the old mellow brick wall of Greenwich Park that skirts the heath on the northern side. (25)

Harper goes on to record that Blackheath was a popular meeting-place in English history, and the “mutinous intent” of Dickens’ horses to return the carriage to Blackheath might be taken as an allusion to Blackheath’s history as a site of collusion and revolt. Two famous revolts – one led by Wat Tyler in 1381 and another by Jack Cade in 1450 – began with the gathering of rebels on Blackheath; and the place gained a milder reputation as a rendezvous for various more peaceful assemblies. As Harper puts it:

As for Blackheath, it seems that when, in older days, people had assignations on the Dover Road, they generally selected this place for the purpose; whether they were kings and emperors that met; or ambassadors, archbishops, rebels, or rival pretenders to the crown, they each and all came here to shake hands and interchange courtesies, or to speak with their enemies in the gate. It is very impressive to find Blackheath thus and so frequently honoured by the great ones of the earth; but it is also not a little embarrassing to the historian who wants to be getting along down the road, and yet desires to tell of all the pageants that here befell, and how the high contending parties variously saluted or sliced one another, as the case might be. Indeed, to write the history of Blackheath would be to despair of ever seeing Dover…. (27)

jack-boots

Jack-boots, according to Fairholt’s

Costume in England: A History of Dress (1860), are “large boot[s],

reaching above the knee, introduced in the seventeenth century” (514).

This illustration, from Fairholt’s Costume, gives

us an idea of the kind of boots the coach-passengers are wearing as they trudge

up Shooter’s Hill beside the mail.

… every posting-house and

ale-house …

A posting-house was named for the post – the conveyance

of letters around the country. To travel or ride post was, in one sense, to ride

with the mail, and a posting-house was a kind of way station where travelers

could change horses and refresh themselves in the course of a journey

(OED).

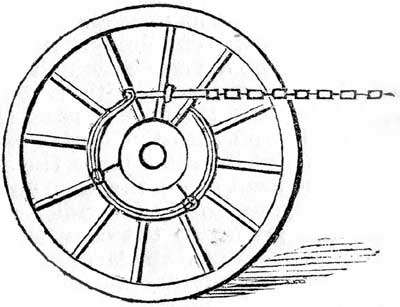

…the guard got down to skid the wheel for the

descent…

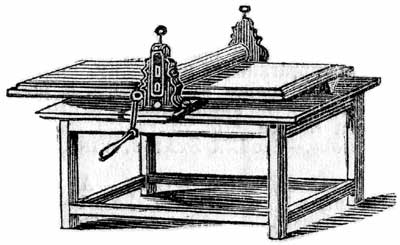

A skid, according to the Dictionary of Daily Wants

(1859), is

An implement used for attaching to the hind-wheel of a vehicle when about to proceed down hill, with a view of regulating its momentum. No carriage or other vehicle should be without this convenience, as it is rarely applied, is never in the way, and prevents accidents and damage. An implement acting on the same principle as the skid, and known as a stop-drag, consists of five or more pieces of wood, united on the outside by a strong joined iron hoop, the wood pressing on the nave of the wheel. The annexed figure [see illustration] shows a wheel on a declivity, the chain drawn tight by the pressure of the breeching on the horse; the brake closely surrounding the nave, and forming an effectual drag. (917)

In other words, a “skid” was a kind of brake for a

carriage-wheel, which operated by friction against the motion of the vehicle and

saved it from running away down hills.

‘I belong to Tellson’s Bank.

You must know Tellson’s Bank in London.

Tellson’s Bank, in London, is

based on the banking house of Child & Co., which was located in Fleet Street

and “leased rooms over Temple Bar as a repository for their cash-books and

ledgers” (Sanders 35). The association becomes clearer later in the novel, when

we visit Tellson’s in Fleet Street next to Temple Bar.

Wait at Dover

for Ma’amselle.

“Ma’amselle” is a phonetic and abbreviated rendering

of the French word “Mademoiselle,” meaning “Miss” or young woman.

…a

smaller chest beneath his seat, in which there were a few smith’s tools, a

couple of torches, and a tinder-box. For he was furnished with that

completeness, that if the coach-lamps had been blown or stormed out, which did

occasionally happen, he had only to shut himself up inside, keep the flint and

steel sparks well off the straw, and get a light with tolerable safety and ease

(if he were lucky) in five minutes.

A smith’s tools are the tools of

a blacksmith – presumably not the larger ones in this case (such as anvils), but

perhaps hammers, files, and the like. An 18th-century torch would have consisted

of “a stick of resinous wood, or of twisted hemp or similar material soaked with

tallow, resin, or other inflammable substance” (OED); and a tinderbox

is a box in which tinder is kept, sometimes along with the flint and steel with

which a spark was struck (OED). The coach-man, to relight the

coach-lamps, would have to “shut himself up” inside the coach to keep the sparks

out of the wind, and would also have to keep them “well off the straw” that was

used inside carriages to insulate against cold in the winter (Sanders 40).

By the time Dickens was writing A Tale of Two Cities,

several kinds of matches had been developed: The first friction matches

(which were lit by running the tip of the match through sandpaper) appeared in

1826; Lucifer matches were sold in London beginning in 1829; phosphorus matches

(instead of sulphur) were available beginning in 1839; and safety matches

appeared in 1855 – a few years before A Tale of Two Cities was composed.

The first half of the 19th century, then, saw remarkable innovations in “getting

a light,” and Dickens’ frequent pejorative references to the old method of

“flint and steal” (he makes fun of the process in Great Expectations also) may relate to the

fact that he was 14 before the first friction matches appeared. The carriage

lamps described in this passage would have been oil-lamps.

After that

there gallop from Temple-bar …

The messenger, Jerry Cruncher, has

galloped from Temple Bar (a large gate marking the entrance to the City of

London between London and Westminster [Gaspey, vol.1, 51]). Temple Bar is

a little over a mile west of London Bridge (where the Dover Road begins), so the

gallop to catch the mail-coach at Shooter’s Hill would be a gallop of a little

over nine miles (Harper, “The Road to Dover”).

The relative locations of

Temple Bar and London Bridge are visible on this portion of Thornton’s map of

London (1784). Temple Bar is at the far left, next to Fleet Street and under

Chancery Lane; London Bridge is the second bridge to the right, just visible at

the bottom of the map to the right of the cease.

…his own coach and six, or his own coach and sixty…

A coach and six is a coach drawn by six horses; a coach and sixty would

be a coach drawn by sixty horses (OED, “chaise”).

…an old

cocked-hat like a three-cornered spittoon…

Dickens is here describing

the kind of three-cornered hat worn by men in the 18th century, familiar to us

from historical paintings and costume dramas. Planché’s History of British Costume (1847) describes

the state of the three-cornered hat during the reign of George III (during which

A Tale of Two Cities is set) as follows:

[A]t the commencement of the reign of George III (1760), we are told, … hats are now worn upon an average six inches and three-fifths broad in the brim, and cocked between Quaker and Kevenhuller. Some have their hats open before like a church spout, or the scales they weigh flour in; some wear them rather sharper, like the nose of a greyhound, and we can distinguish, by the cock of the hat, the mode of the wearer’s mind. There is the military cock; and the mercantile cock; [etc.] (403)

The comparisons made here (of the three-cornered hat to a

church spout, a flour-scale, a greyhound’s nose, etc.) suggest that Dickens’

comparison of the three-cornered hat to a spittoon participates in a tradition

of pejorative similes. (A spittoon is a “receptacle for spittle, usually a round

flat vessel of earthenware or metal” [OED] in which saliva and tobacco

might be deposited; the shallow basin of the spittoon must have borne some

resemblance to the hat’s shallow crown.)

The three-cornered hat was the

typical head-dress for men until the late 18th century, and Planché attributes

its demise to the French Revolution:

[T]he French Revolution, in 1789, completed the downfall of the three-cornered cocked hat on both sides of the Channel [i.e. in both England and France]. It was insulted in its decay by the nick-name of “an Egham, Staines, and Windsor,” from the triangular direction post to those places which it was said to resemble…. (403)

To modify the abuse heaped here upon the cocked hat, we may look at the remarks that defend it – at least to the extent of abusing its replacement. F.W. Fairholt’s Costume in England (published in 1860, and thus roughly contemporary with A Tale of Two Cities) remarks that:

[T]he French Revolution of 1789 very much influenced the English fashions, and greatly affected both male and female costume; and to that period we may date the introduction of the modern [1860] round hat in place of the cocked one; and it may reasonably be doubted whether anything more ugly to look at, or disagreeable to wear, was ever invented as a head-covering for gentlemen. Possessing not one quality to recommend it, and endowed with disadvantages palpable to all, it has continued to be our head-dress till the present day, in spite of the march of the intellect it may be supposed to cover. It [is not] seen in Parisian prints before 1787. (326)

This illustration, from Fairholt’s Costume, shows the change in men’s hats from the 1780s to the turn of the century.

From left to right, the figures in the illustration above show

a "large round hat" of 1786, the "last form" of the cocked-hat, and a round hat

which came into vogue in 1792 (during the period of the French Revolution) and

was still worn, "with little variation," when Dickens and Fairholt were writing

(Fairholt 508).

It [Jerry’s hair] was so like smith’s work, so much

more like the top of a strongly spiked wall than a head of hair, that the best

players at leap-frog might have declined him, as the most dangerous man in the

world to go over.

A blacksmith works in metal, and could thus be

responsible for forging the spikes to which Jerry’s hair is compared. The game

of leapfrog, which the OED locates in

English usage from the 16th century onward, is “A boys’ game in which one player

places his hands upon the bent back or shoulders of another and leaps or vaults

over him” – a dangerous game to play over metal spikes or, by comparison, Jerry

Cruncher.

…the strong-rooms underground…

A strong-room is,

according to the OED, “A room made specially secure for the custody of

persons or things; esp[ecially] a fire- and burglar-proof room in which

valuables are deposited for safety, e.g. at the Mint, a bank,

etc.”

…he went in among them with … the feebly-burning candle…

In 1775, indoor lighting consisted either of candlelights or oil-lamps.

The general state of lighting in the late 18th century was primitive. In

buildings, gas lighting was an invention of the very late18th century (first

used to light a factory in Manchester in 1798) and was not implemented in London

until 1807, and in Paris until 1819 (Hobsbawm 298). Electrical lighting of the

sort we enjoy now did not appear until long after A Tale of Two Cities

was written; it was first implemented in London in 1882.

…the

head-drawer at the Royal George Hotel opened the coach door, as his custom

was.

The Royal George Hotel is usually identified as the Ship Hotel

in Dover (Sanders 39), demolished in 1860 (the year after A Tale of Two

Cities was published) to make way for a new portion of the railway. It is

probably the hotel commemorated in Byron’s Don

Juan (1821) in this facetious apostrophe:

Thy cliffs, dear Dover! Harbour and hotel;

Thy custom-house, with all its delicate duties;

Thy waiters running mucks at every bell;

Thy packets, all whose passengers are booties

To those who upon land or water dwell;

And last, not least, to strangers uninstructed,

Thy long, long bills, whence nothing is deducted. (qtd. in Harper 243)

A drawer is “[o]ne who draws liquor for customers; a tapster at a tavern” (OED).

…packet to Calais…

A “packet,” according to the

OED, is short for “packet-boat,” or a “boat or vessel plying at regular

intervals between two ports for the conveyance of mails, also of goods and

passengers; a mail-boat.” The derivation of the word seems to relate to the

progress of the mails, and especially state papers and dispatches, between

England and the Continent: A “packet” was originally “the boat maintained for

carrying ‘the packet’ of State letters and dispatches…. An early official name

for this was POST-BARK (in State Papers as late as 1651), also POST-BOAT….

[T]his ‘Boate to Transport the Packetts’ was prob[ably] already familiarly known

as the ‘packet-boat,’ since this term was so well-known as to be borrowed in

French before 1634.” Mr. Lorry’s conveyance from England to France was thus the

usual one in 1775, and the crossing – from Dover to Calais – was also the usual

one. The distance between Dover and Calais (the towns closest to one another

across the Channel) was about 22 nautical miles (Baedeker 15) or 8 leagues

(Tronchet xxv).

This map, from Tronchet’s Picture of Paris (c.

1818), shows the route of packets from Dover to Calais. It also, incidentally,

maps the Dover Road (though not in great detail – only a few points between

London and Dover are labeled).

“…but I want a bedroom, and a barber.”

A

barber could be employed for a haircut, a shave, or both. Mr. Lorry, who wears a

wig, probably wants a barber for a shave; however, since men who wore wigs often

kept their actual hair very short or shaved, he may want a haircut as

well.

“Show Concord! Gentleman’s valise and hot water to Concord. Pull

off gentleman’s boots in Concord. (You will find a fine sea-coal fire,

sir.)...”

“Concord,” here, is the name of a specific room or set of

rooms in the Royal George Hotel. A “Concord” was a kind of traveling coach named

after Concord, New Hampshire (Sanders 40); and a “sea-coal fire” is a fire made

up with coal in the ordinary sense. The word “sea-coal” is used, according to

the OED, to distinguish coal (used for heating) from charcoal. Though

it is sometimes thought that the name “sea-coal” derived from the process of

shipping coal by sea from locations in the north of England (such as Newcastle),

the OED considers this derivation doubtful because early usages of the

word occur even in coal-producing regions (to which coal would not have been

shipped by sea). The OED suggests instead that “in early times the

chief source of coal supply may have been the beds exposed by marine denudation

on the coasts of Northumberland and South Wales.” In any case, sea-coal is the

same as regular coal, and is used by the employees of the Royal George to

distinguish their coal fires from charcoal fires – and thus to indicate the

quality of the fire Mr. Lorry is about to enjoy. Charcoal was a cheaper fuel,

but less pleasant and apparently somewhat hazardous. According to the

Dictionary of Daily Wants (1859):

Although charcoal is an economical fuel, it is by no means conducive to health, and is sometimes attended with dangerous consequences. Wherever charcoal is burnt a vessel of boiling water should be set over the burning fuel, the steam from which will counteract the dangerous fumes of the carbon. If a little vinegar be added persons will be much less liable to headaches than they otherwise are. When a person has inhaled the fumes of charcoal to such a degree as to become insensible, he should be immediately removed into the open air, cold water dashed on the head and body, the nostrils and lungs stimulated by hartshorn, at the same time rubbing the chest briskly. (263-4)

Coal, therefore, though more expensive, was preferred to charcoal for heating domestic spaces. The Dictionary of Daily Wants gives the following directions concerning its use:

The economy of coal is a great consideration, especially where a number of fires are kept burning at one time. The chief principles are, to make a good fire at once, not to poke it too frequently, and to burn the cinders that fall beneath, by throwing them on to the fire from time to time, instead of suffering them to accumulate, and ultimately perhaps to be thrown away. The properties of coal when burning, are generally speaking not injurious to the health, especially when employed in open fire-places, or in stoves where there is a free egress for the sulphur and ammonia evolved; but if the chimney or stove smokes, the head and lungs may be seriously affected by the quantity of sulphur and ammonia confined in the room; and instances have been known where fatal consequences have attended imperfect draughts. (296)

…a gentleman of sixty, formally dressed in a brown suit of

clothes, pretty well worn, but very well kept, with large square cuffs and large

flaps to the pockets, passed along on his way to breakfast…. Very orderly and

methodical he looked, with a hand on each knee, and a loud watch ticking a

sonorous sermon under his flapped waistcoat…. He had a good leg, and was a

little vain of it, for his brown stockings fitted sleek and close, and were of a

fine texture; his shoes and buckles, too, though plain, were trim. He wore an

odd little flaxen wig, setting very close to his head: which wig, it is to be

presumed, was made of hair, but which looked far more as though it were spun

from filaments of silk or glass….

Mr. Lorry’s brown suit of clothes

identifies him as a well-groomed, modestly dressed gentleman of the 18th

century. In 1775, however, his square coat-cuffs and the flaps on his coat and

waistcoat were not in the latest fashion, belonging to the style of a somewhat

earlier period: According to Planché's History of British Costume

(1847), this style of clothing belonged to the “reign of Queen Anne

[1702-14] and the first two Georges [1714-60]” (403-4), and began to change

during the reign of George III. Beginning in 1772, “fashionable” gentlemen

(primarily the wealthy) began to wear waistcoats “much shortened, reaching very

little below the waist, and being without the flap-covered pockets” (Fairholt

318). Coats were also shortened, and “[a] watch was carried in each pocket, from

which hung bunches of chains and seals” (Fairholt 318). Mr. Lorry, then, is well

dressed in 1775, but not “fashionably” so, and adheres to a style of the earlier

18th century (indeed, the “pretty well worn” state of his suit suggests that,

though neatly dressed, he has adhered to the same mode for some time). Even his

watch, as obtrusive as it seems to be – “a loud watch ticking a sonorous sermon”

– is apparently a symbol of sartorial restraint: Not only does it tick

sonorously beneath the outmoded flaps of his waistcoat, but the fact that there

is only one watch (instead of one for each pocket), and no “bunches of chains

and seals,” suggests that he is very modestly accoutered.

Moreover, with

shorter waistcoats, multiple watches, and a lack of flaps, 1772 introduced wigs

of considerable size – “enormous hair-do[s],” as one 19th-century writer puts it

(Fairholt 318) – for fashionable gentleman. Mr. Lorry’s wig, however, remains

“little”; and though Dickens’ description of it as an “odd little wig” refers to

the fact that it would have been odd for his 19th-century readers to

see one, it would – like the rest of Mr. Lorry’s outfit – have been proper in

1775 (though not especially fashionable).

Finally, having a “good leg” means that Mr. Lorry’s leg – in

tight-fitting breeches to the knee – is shapely. From “the close of G[eorge]

II’s reign [onward, breeches were] worn over the stocking … and fastened first

by buckles and afterwards by strings” (Planché 403-4). Shoes likewise, for both

men and women, were buckled – just as Mr. Lorry’s are – and had heels. Buckles

did not become unfashionable until the period of the French Revolution, when

shoe-laces began to replace them and shoes began to grow flatter in the heel.

When this began to happen, “[t]he Prince of Wales was petitioned by the alarmed

buckle-makers to discard his new-fashioned strings, and take again to buckles,

by way of bolstering up their trade; but the fate of these articles was sealed,

and the Prince’s compliance with their wishes did little to prevent their

downfall” (Fairholt 326).

The little narrow, crooked town of Dover hid

itself away from the beach, and ran its head into the chalk-cliffs, like a

marine ostrich.

Dover is famous for its “white cliffs” – white

because they are composed of chalk – and is described by Lyon’s History of

the Town and Port of Dover (1813) as

…a healthy situation, as it is built chiefly upon chalk, or pebbles, and there is a rapid descent, to carry off all impurities to the sea. The town in sheltered by the high hills, from the easterly and northerly winds, and it is much warmer in the winter than some other towns on the coast. (36)

In 1775, the date of Mr. Lorry’s visit to Dover, the town was

apparently in need of some municipal repair; an act of parliament was passed in

1778 “for new paving, watching, and lighting of the town” (Lyons 37).

Dickens’ description of the town as a “kind of marine ostrich” refers to

the notion that ostriches hide their heads in the sand. According to Sanders’

Companion to A Tale of Two Cities, Dickens possessed a copy of

Oliver Goldsmith’s History of the Earth and Animated Nature, which

describes ostrich behavior as follows:

Upon observing himself … pursued at a distance he begins to run at first gently; either insensible of danger or sure of escaping…. At last, spent with fatigue and famine, and finding all power of escape impossible, he endeavours to hide himself from those enemies he cannot avoid, and covers his head in the sand, or the first thicket he meets. (qtd. in Sanders 41)

The belief that ostriches hide their heads in the sand is of long standing. The OED notes that the

…habits and peculiarities of the bird, real and fabulous, have afforded much scope for proverb and allusion; such are its indiscriminate voracity and its liking for hard substances, which it swallows to assist the gizzard in its functions; its supposed want of regard for its young, its eggs being partly hatched by the heat of the sun, which has led to the belief that it deserts its nest; and the practice attributed to it of thrusting its head into the sand or a bush when being overtaken by pursuers, through incapacity to distinguish between seeing and being seen.

Among these many “habits and peculiarities” attributed to the

ostrich, however, the alleged habit of sticking its head in the sand is perhaps

the most popular. Carlyle, for instance, invokes the figure of the ostrich near

the beginning of The French Revolution

by way of describing Louis XV’s avoidance of the mention of death: “It is the

resource of the Ostrich; who, hard hunted, sticks his foolish head in the

ground, and would fain forget that his foolish unseeing body is not unseen too”

(18).

…a strong piscatory flavour…

According to the OED, a “piscatory flavour” would be a fishy

one. “Piscatory” means “[o]f or pertaining to fishers or to

fishing.”

A little fishing was done in the port, and a quantity of

strolling about by night, and looking seaward: particularly at those times when

the tide made, and was near flood. Small tradesmen, who did no business

whatever, sometimes unaccountably realized large fortunes, and it was remarkable

that nobody in the neighborhood could endure a lamplighter.

According

to Sanders, the “quantity of strolling about by night” is an allusion to the

number of smugglers who operated in Dover, smuggling goods – especially brandy –

into England from France. Dickens’ reference to “small tradesmen, who did no

business whatsoever” may allude to the smugglers’ euphemism for their business –

“free trade” (Sanders 41). The smugglers’ aversion to lamp-lighting is

understandable (light compromising discretion), and Sanders notes that the

smugglers went out to sea with their own lamps to guide boats with contraband

materials on board to shore.

A lamplighter, of course, was one who lit the lamps in a town.

Before electric light (which did not appear in cities until the end of the 19th

century), lamplighters were employed to light the street-lamps at night, and

usually carried ladders (which they ascended to light the lamps). To say that

someone was “like a lamplighter” was, according to the OED, a tribute

to his or her swiftness.

…the air, which had been at intervals clear

enough to allow the French coast to be seen…

Dover and Calais, in

England and France respectively, are the cities closest to one another across

the English Channel – a distance of 22 nautical miles or 8 leagues (Baedeker,

Tronchet). On a clear day, the coasts would be visible to one another.

claret

According to the Dictionary of Daily Wants

(1859), claret is “[o]ne of the most wholesome of the light wines. It contains

15.10 percent of alcohol ... [and] is useful in many cases of convalescence from

febrile complaints, where heavier and stronger wines would be inadmissible”

(290). Modern clarets tend to have an alcohol content of 14% or less, which

suggests either that wine was more potent in the 18th and 19th centuries than it

is at the present time, or that measurements were less exact. Describing claret

as one of the “light” wines, the Dictionary of Daily Wants compares it to

“stronger” or comparatively “generous” wines like sherry, port, or Madeira. The

latter, it says, may “be advantageously diluted with water” (1112).

It

was a large, dark room, furnished in a funereal manner with black

horsehair…