|

NOTES ON ISSUE 12: GLOSSARY

PART 3 OF 3

No fight could have been half so

terrible as this dance. It was so emphatically a fallen sport – a

something once innocent delivered over to all devilry – a healthy

pastime changed into a means of angering the blood, bewildering the

senses, and steeling the heart.... This was the Carmagnole.

The “Carmagnole,” a patriotic dance

“popular among the French revolutionists of 1793” (OED),

originally referred to “a kind of dress much worn in France during the

Revolution of 1789” (OED). This dress, named after the Italian

town of Carmagnola, was a Piedmontese peasant costume well known in

southern France (Piedmont, a region of northwestern Italy, is adjacent

to the southeastern part of France), and introduced into Paris by the

Marseillais revolutionaries in 1789 (Marseilles is a coastal city in

southern France, on the Mediterranean). It

consisted of a short skirted coat

with rows of metal buttons, a tricoloured waistcoat and red cap, and

became the popular dress of the Jacobins. The name was then given to

the famous revolutionary song, composed in 1792, the tune of which, and

the wild dance which accompanied it, may have also been brought into

France by the Piedmontese. (“Carmagnole,” 1911 Edition Encyclopedia)

The lyrics to the Carmagnole varied during

the course of the Revolution, but originally calumniated Louis

XVI (as “Monsieur Veto” because of his power to

delay the proposals of the revolutionary legislature [until

his seizure and imprisonment after August 10, 1792]), and later

Marie-Antoinette (as “Madame Veto” – apparently

as the consort of Monsieur Veto, Louis XVI). Lyrics and a recording

of the Carmagnole as it would have been sung in late 1793 (after

the beheading of Marie-Antoinette in October) can be accessed

at the website “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring

the French Revolution,” under “Songs,” http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution.

(From the main page, either do a “Quick Search”

for “Carmagnole” or click on “Browse”

and scroll down to “Songs”; then, in “Browse

Songs,” scroll down and click on “The Carmagnole.”)

He has not received the notice yet, but I know that he will presently

be summoned for to-morrow, and removed to the Conciergerie…

The Conciergerie, the oldest prison in Paris, is adjacent to the Palais

de Justice on the Ile de la Cité. During the Revolution, it was

the prison to which suspects were removed just before trial; thus,

Darnay’s summons to the Conciergerie means that his trial is imminent.

In the 19th century, the Conciergerie was still used as a prison for

those awaiting trial, and the chamber of Marie-Antoinette (perhaps the

most famous person to have been held there during the Revolution) was

converted into a chapel. This chamber was gutted by fire in 1871

(Baedeker 219), but afterwards restored, and can still be seen today.

The Conciergerie is visible on this portion of

the Plan de la Ville de Paris, Période

Révolutionnaire, 1790-1794 (on the northwestern

side of the Ile de la Cité, just above the Palais de

Justice).

Click on

map for larger view

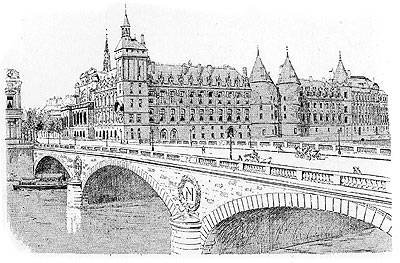

This image of the Conciergerie (below), with

the Seine in the foreground, is taken from Dumas’ Paris

(1889). Though the Conciergerie underwent considerable

rebuilding and restoration in the 19th century (before this

illustration was created), many of the oldest parts of the building

remain to this day. For instance, the pointed towers date

from the 14th century, and would have been familiar to those

incarcerated in the Conciergerie during the French Revolution.

The dread Tribunal of five Judges, Public

Prosecutor, and determined Jury, sat every day.

This “dread Tribunal” is the revolutionary judicial body which –

particularly active during the Reign of Terror – decided the fate of

those, like Darnay, who were suspected of being traitors to the

Revolution. Dickens’ anatomy of this Tribunal follows Carlyle’s account

in The French Revolution:

Very

notable also is the Tribunal Extraordinaire: decreed by the

Mountain [the Jacobin party]; some Girondins [the moderate

revolutionary party ultimately demolished by the Jacobins] dissenting,

for surely such a Court contradicts every formula; – other Girondins

assenting, nay co-operating, for do not we all hate Traitors, O ye

people of Paris?… Five Judges; a standing Jury, which is named from

Paris and the Neighborhood, that there be not delay in naming it: they

are subject to no appeal; to hardly any Law-forms, but must “get

themselves convinced” in all readiest ways; and for security are bound

“to vote audibly”; audibly, in the hearing of a Paris Public. This is

the Tribunal Extraordinaire; which, in a few months, getting

into most lively action, shall be entitled Tribunal

Révolutionnaire; as indeed it from the very first has

entitled itself: with a Herman and a Dumas for Judge President, with a

Fouquier-Tinville for Attorney-General, and a Jury of such as Citizen

Leroi, who has surnamed himself Dix-Août, "Lerio August-Tenth” [in

commemoration of the day the King was suspended from office, previous

to his incarceration and execution], it will become the wonder of the

world. Herein has Sansculottism fashioned for itself a Sword of

Sharpness: a weapon magical; tempered in the Stygian hell-waters; to

the edge of it all armour, and defence of strength or of cunning shall

be soft; it shall mow down Lives and Brazen-gates; and the waving of it

shed terror through the souls of men. (623-4)

Ultimately, at the height of the

Terror, this Tribunal was extended into four Tribunals, and the rate of

execution was sped proportionally (Carlyle 730).

…some games of forfeits and a little concert, for

that evening.

The Dictionary of Daily Wants (1859) describes the “game of

forfeits” as follows:

FORFEITS.

– A pastime usually played by a number of persons of both sexes. The

ordinary mode is to select some sentence, which each person of the

party is to repeat without making a mistake, and in the event of his so

doing, he has to forfeit to some person chosen for the purpose any

trifling article, such as a card-case, smelling-bottle, fan, &c.

When the sentence has gone the round of the party, one of the company

has to kneel with her head in the lap of the person holding the

forfeits; this latter person holds up the forfeits one by one in sight

of the whole company, and says, “Here’s a pretty thing, a very pretty

thing, and what’s to be done to the owner of this pretty thing?” The

person kneeling down has then to impose some penalty which involves

some ludicrous situation, and is calculated to produce laughter and

good humour among the company present. This accomplished, the forfeited

article is returned to the owner. By this it is evident that the person

who has to impose the forfeits should possess a fund of humour and

ready invention; and, to ensure uninterrupted sport, some person should

be selected gifted with these attributes. (440)

Under the circumstances (incarceration

prior to execution by guillotine), this game seems somewhat

horribly appropriate, for the very name invokes a penalty or loss (a

forfeit is something the right to which is lost through the

commission of a crime or a fault of some kind [OED]).

Charles Evrémonde, called Darnay, was

accused by the public prosecutor as an aristocrat and an emigrant,

whose life was forfeit to the Republic, under the decree which banished

all emigrants on pain of Death.

On September 17, 1793, the Revolutionary government decreed that,

according to a new “Law of the Suspect,” France be purged of its

nobility (as Carlyle describes it, “…so has the Convention decreed: Let

Aristocrats, Federalists, Monsieurs vanish, and all men tremble: ‘the

Soil of Liberty shall be purged,’ – with a vengeance!” [667]).

Darnay, entering France in August of

1792, returned before the laws under which he is tried had officially

been passed.

On his coming out, the concourse made at him anew,

weeping, embracing, and shouting, all by turns and all together, until

the very tide of the river on the bank of which the mad scene was

acted, seemed to run mad, like the people on the shore.

The river “on the bank of which the mad scene” is acted is of course

the Seine. The Conciergerie, standing on the north side of the Ile de

la Cité, looks out over the river.

Then, they elevated into the vacant chair a young

woman from the crowd to be carried as the Goddess of Liberty…

Dickens’ representation of this impromptu elevation of a “Goddess of

Liberty” probably draws on various acts of patriotic idolatry described

in Carlyle’s French Revolution. On August 10, 1793, a huge

terra-cotta statue of “Liberty” was unveiled in the Place de la

Révolution (Carlyle 657-8), on the site of the former

statue of Louis XV (which had been erected when the Place de la

Révolution was still the Place de Louis XV); and on November 10,

1793, a “Goddess of Reason” was installed in Notre Dame (which itself

was newly converted into a “Temple of Reason”). Carlyle describes this

goddess’ elevation as follows:

For

this same day, while [the] brave Carmagnole-dance has hardly jigged

itself out, there arrive Procureur Chaumette and Municipals and

Departmentals, and with them the strangest freightage: a New Religion!

Demoiselle Candeille, of the Opera; a woman fair to look upon when well

rouged; she, borne on palanquin shoulder high; with red woolen

night-cap; in azure mantle; garlanded with oak; holding in her hand the

Pike of the Jupiter-Peuple, sails in; heralded by white young

women girt in tricolor. Let the world consider it! This, O National

Convention wonder of the universe, is our New Divinity, Goddess of

Reason, worthy, and one worthy of revering. Her henceforth we

adore. Nay, were it too much to ask of an august National

Representation that it also went with us to the ci-devant

Cathedral called of Notre-Dame, and executed a few strophes in worship

of her? (696)

Demoiselle Candeille of the

Opéra was not the only woman elevated to goddess-status for this

Feast of Reason; others were elevated in other churches, and Carlyle

notes that one “Mrs. Momoro, it is admitted, made one of the best

Goddesses of Reason; though her teeth were a little defective” (697).

It was the ordinance of the Republic … that on the

door or doorpost of every house, the name of every inmate must be

legibly inscribed in letters of a certain size, at a certain convenient

height from the ground.

Dickens draws this detail of the house-doors directly from Carlyle, who

notes that

In

Paris and all Towns, every house-door must have the names of the

inmates legibly printed on it, “at a height not exceeding five feet

from the ground”; every Citizen must produce his certificatory Carte

de Civisme signed by Section-President; every man be ready to give

account of the faith that is in him. (623)

“Old Nick’s.”

Old Nick is a name for the devil; the derivation of this nick-name,

however, has never been successfully traced (OED).

Bibliographical information

|