|

NOTES ON THE NOVEL: ISSUE 11

Printable View

A Note on the Maps:

The maps used to illustrate this issue are reproduced

from Collins' Illustrated Atlas of London, published

in 1854. Pip's London would have been that of the 1820s, and Dickens'

London, at the time he was composing the novel, was that of 1860-1.

Collins' maps thus represent a London that falls between the historical

moment represented in the novel and the historical moment of the

novel's composition.

Since the chapters in this issue (Chs. 34-37)

take place in the mid-1820s (Meckier 179), the maps used here show

a city that has undergone about 30 years of change since Pip's time.

Nevertheless, they are very useful in tracking Pip's progress through

the city; the reader should merely keep in mind that some of the

landmarks would not have existed in the mid-'20s. The most significant

of these are the railway lines marked on the Key Map -- the

railroad did not enter London until the late 1830s and early 1840s

(Tallis's Illustrated London 186-7). The Key Map also

shows a bridge that Pip would not have recognized -- the Hungerford

Bridge between Waterloo and Westminster Bridges. And London Bridge

was, in Pip's time, Old London Bridge -- a different structure,

but built in essentially the same place. (New London Bridge would

have begun construction a few yards from Old London Bridge when

Pip was living in London, but would not have replaced the old bridge

during his tenure [Meckier 162]. Given that both London Bridges

would have been mapped in the same place, the difference between

the bridges makes no difference to our reading of the map.) Any

further discrepancies will be noted where appropriate.

History and features of Collins' Atlas

(1854)

Collins' Atlas was created in response

to the amplified tourist trade in London resulting from the Great

Exhibition of 1851. Previous to the Atlas, maps tended to

be very large and unwieldy, and though large city maps could be

folded up and carried, Collins designed his maps with a specific

view to portability (Dyos 10). The Atlas consists of one

large map of the whole city of London (the Key Map), followed

by 36 plates. The Key Map is drawn with numbered sections,

and these sections are represented in detail by the plates (the

numbers on the Key Map refer to the numbers of the plates).

The chief drawback to the Atlas is that, although the Key

Map keeps North at the top, the plates do not always observe

this convention (Dyos 13). This disregard of the compass, however

puzzling to someone attempting to navigate London in 1854, is in

many respects an advantage for the modern reader: The detailed plates

-- drawn to represent popular views of the city and/or popular routes

through it -- give us a unique view of the sites of Pip's adventures

in 19th century London. Any major discrepancies between the landmarks

shown on the maps and those that Pip would have been acquainted

with (given that the map was composed in 1854, about thirty years

after Pip's tenure in London) will be indicated where appropriate.

A Note on the Illustrations

Like Collins' Atlas, the engraved illustrations

of London reproduced in this and subsequent issue(s) were prepared

as a result of the Great Exhibition of 1851. Tallis's Illustrated

London (published in 1851-2, in two volumes) was created specifically

to commemorate the Exhibition, and furnishes, not only a great many

engravings of London scenes, but also a long history of, and commentary

on, the sights of London. Since Tallis's Illustrated London

was published, like Collins' Atlas, about 30 years after

Pip's tenure in the city, some of the views commemorated in Tallis's

would not have been available to Pip. Thus, only those illustrations

that show cityscapes and landmarks as they would have appeared to

Pip in the 1820s have been included here.

A tour of chapters 34-37

The Key Map of Collins' Atlas,

showing London as a whole, gives a useful overview of the locations

mentioned in this issue. Most of the locations referred to in Chapter

34-37 are clustered around a portion of the Thames, in -- or in

the vicinity of -- area 1 (shown in detail on Plate 1). All of the

maps reproduced here have been highlighted for convenience of reference

and increased legibility.

Covent Garden, where Pip and his club — the "Finches"

— dine extravagantly, is visible on Plate 1 of Collins'

Atlas (below), at the lower right side. As indicated previously,

Hungerford Bridge, which appears on this Plate, would not have existed

in Pip's time.

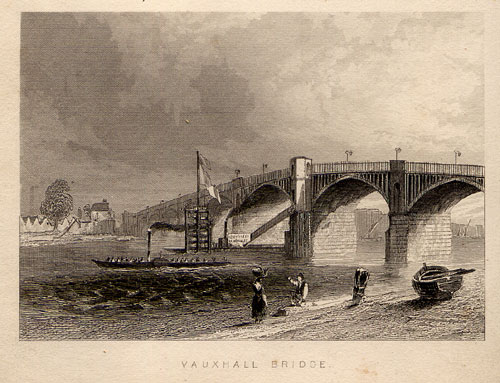

When Pip asks Wemmick's opinion about doing a monetary favor for

a friend, Wemmick -- in his professional capacity -- lists "the

names of the various bridges up as high as Chelsea Reach. Let's

see; there's London, one; Southwark, two; Blackfriars, three; Waterloo,

four; Westminster, five; Vauxhall, six" (Ch. 36). (He advises Pip

to throw his money off the side of one of them.) These bridges are

all visible on the Key Map (see Key Map again above).

Hungerford Bridge, also represented on the map, was not built until

1845, and Battersea Bridge, though built in the late 18th century,

is beyond the scope of Wemmick's reckoning.

Tallis's Illustrated London includes illustrations

of Waterloo, Westminster, and Vauxhall bridges.

Wemmick's Aged Parent was employed in Wine-Coopering,

first in Liverpool, and then in London. The respective locations

of these two cities are shown below.

Taught the young idea how to shoot: When

Pip relates that Mrs. Pocket "taught the young idea how to shoot,

by shooting it into bed whenever it attracted her notice" (Ch. 34),

he makes a jesting allusion to James Thomson's long poem Spring

-- specifically to lines 1152-3: "Delightful task! To rear the tender

thought, / To teach the young idea how to shoot." In Mrs. Pocket's

case, of course, her rearing of the tender shoot is somewhat on

the thoughtless side, as her child is gotten out of sight and mind

with great rapidity. Spring is part of The Seasons,

which appeared between 1726-1730. The Seasons was a very

popular poem, and Thomson was influential for Romantic writers like

Wordsworth (Oxford Companion 989-90). He is also famous for

having composed the poem "Rule Britannia," which was later set to

music by Arne (see Issue

10 for a note on a reference to "Rule Britannia" in Great

Expectations).

Humanity ... brought nothing into the world

and can take nothing out, ... it fleeth like a shadow and never

continueth long in one stay: When Pip refers to these "noble

passages," he alludes to the "Order for the Burial of the Dead,"

read at funerals. The first few lines in the "Order" are taken from

specific passages in the bible (indicated in brackets): "We brought

nothing into this world, and it is certain that we can carry nothing

out [1 Timothy 6:7]. The Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away

[Job 1:21]. Man that is born of a woman hath but a short time to

live, and is full of misery. He cometh up, and is cut down, like

a flower; he fleeth as it were a shadow, and never continueth long

in one stay" (Mitchell 500).

Funeral execution: Joe's desire to have

a simple funeral for Mrs. Joe — "'I would in preference have

carried her to the church myself, along with three or four friendly

ones wot come to it with willing harts and arms, but it were considered

wot the neighbors would look down on such and would be of opinions

as it were wanting in respect'" (Ch. 35) — is, according to

the Dictionary of Daily Wants (1858-9), perfectly respectful:

"In walking funerals it is considered a mark of respect for friends

to become pall-bearers" (450).

Girdle or cestus: Wemmick's arm, in relation

to Miss Skiffin's waist, is compared to two kinds of belts. A girdle

is a decorative belt (it was not, according to the Oxford English

Dictionary, associated with the undergarment until the 20th

century, and this meaning first came into use in America, not Britain).

A cestus has slightly more conjugal overtones, being a "belt or

girdle for the waist; particularly that worn by a bride in ancient

times" (OED, "cestus").

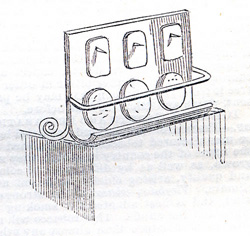

Iron stand hooked on to the top-bar ... a

jorum of tea: When Wemmick's Aged Parent makes "such a haystack

of buttered toast that [Pip] could scarcely see him over it as it

simmered on an iron stand hooked on to the top-bar" (Ch. 37), he

is using an early kind of toaster. The Dictionary of Daily Wants

(1858-9) illustrates this kind of toaster and gives the following

definition:

TOASTER.

-- A culinary utensil, as seen in the engraving, placed upon a

stand of strong wire, that hooks on to the bars of a grate, and

made either loose, or to slide backwards and forwards on the stand;

this will dress bread, cheese, and small pieces of meat. (1005)

A jorum is "a large drinking-bowl or vessel"

(OED, "jorum"), or the contents thereof.

Powder-mill: A powder-mill is a mill (a

factory) for making gunpowder (OED, "powder-mill") and thus,

like the Aged, prone to explosion.

Bibliographical

information

|