|

NOTES ON THE NOVEL: ISSUE 13

Printable View

A Note on the Maps:

Most of the maps used to illustrate this issue

are reproduced from Collins' Illustrated Atlas of London, published

in 1854. Pip's London would have been that of the 1820s, and Dickens'

London, at the time he was composing the novel, was that of 1860-1.

Collins' maps thus represent a London that falls between the historical

moment represented in the novel and the historical moment of the

novel's composition.

Since the chapters in this issue (Chs. 40-42)

take place in late 1828 (Meckier 160), the maps used here show a

city that has undergone over 25 years of change since Pip's time.

Nevertheless, they are very useful in tracking Pip's progress through

the city; the reader should merely keep in mind that some of the

landmarks would not have existed in the late 1820s. The most significant

of these are the railway lines marked on the Key Map -- the

railroad did not enter London until the late 1830s and early 1840s

(Tallis's Illustrated London 186-7). The Key Map also

shows a bridge that Pip would not have recognized -- the Hungerford

Bridge between Waterloo and Westminster Bridges. And London Bridge

was, in Pip's time, Old London Bridge -- a different structure,

but built in essentially the same place. (New London Bridge would

have begun construction a few yards from Old London Bridge when

Pip was living in London, but would not have replaced the old bridge

during his tenure [Meckier 162]. Given that both London Bridges

would have been mapped in the same place, the difference between

the bridges makes no difference to our reading of the map.) Any

further discrepancies will be noted where appropriate.

History and features of Collins' Atlas

(1854)

Collins' Atlas was created in response

to the amplified tourist trade in London resulting from the Great

Exhibition of 1851. Previous to the Atlas, maps tended to

be very large and unwieldy, and though large city maps could be

folded up and carried, Collins designed his maps with a specific

view to portability (Dyos 10). The Atlas consists of one

large map of the whole city of London (the Key Map), followed

by 36 plates. The Key Map is drawn with numbered sections,

and these sections are represented in detail by the plates (the

numbers on the Key Map refer to the numbers of the plates).

The chief drawback to the Atlas is that, although the Key

Map keeps North at the top, the plates do not always observe

this convention (Dyos 13). This disregard of the compass, however

puzzling to someone attempting to navigate London in 1854, is in

many respects an advantage for the modern reader: The detailed plates

-- drawn to represent popular views of the city and/or popular routes

through it -- give us a unique view of the sites of Pip's adventures

in 19th century London. Any major discrepancies between the landmarks

shown on the maps and those that Pip would have been acquainted

with (given that the map was composed in 1854, about thirty years

after Pip's tenure in London) will be indicated where appropriate.

A tour of chapters 40-42

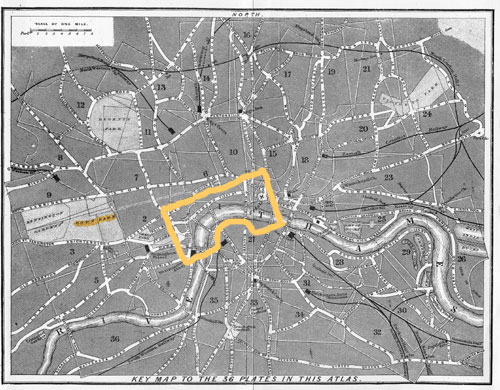

The Key Map of Collins' Atlas (below),

showing London as a whole, gives a useful overview of the locations

mentioned in this issue. For instance, Hyde Park, where Magwitch

hopes that Pip will establish a "'fashionable crib' ... in which

he could have a 'shake down'" (Ch. 40), is visible toward the left

side of the Key Map, next to Kensington Gardens (Pip would

not have had a residence in the park, but in one of the fashionable

neighborhoods in its vicinity). Most of the other locations described

in Chapters 40-42 appear in the area designated by numeral 1 on

the Key Map, and are shown in detail on Plate 1. All of the

maps reproduced here have been highlighted for convenience of reference

and increased legibility.

Pip takes rooms for Magwitch -- under the pretense

that Magwitch is his "Uncle Provis" -- in "a respectable lodging-house

in Essex-street, the back of which looked into the Temple, and was

almost within hail of [his] windows" (Ch. 40). Essex Street appears

on Plate 1 of Collins' Atlas (below), running parallel to

the Temple (at the far right side of the Temple complex) from Temple

Bar to the Thames.

If Magwitch's windows are within hail of Pip's,

Pip's flat in Gardencourt would be at the rightmost corner of the

Temple, bordering on the Thames. This accords with his description

of his rooms in Chapter 39: He says that he and Herbert lived "at

the top of the last house" in the Temple, and that it had "a lonely

character" and was "exposed to the river."

Abel Magwitch tells his life-story in Chapter

42. It begins in Essex County and runs all over England, as well

as to the penal colony of Australia. The map below is a graphic

representation of the locations named in the course of Magwitch's

personal history.

THE EXPLOITS OF ABEL MAGWITCH, 1768-1829

Born, or at least "bec[oming] aware of [him]self"

(Ch. 42), in Essex county, Magwitch spent his youth in and out of

jails. The specific jails named in his narrative are indicated in

red -- the Medway Hulks, whence he escaped and met Pip; Kingston

Jail, whence he was released and met Compeyson; and finally the

penal colony of New South Wales, to which he was transported for

life. Locations associated with Compeyson are marked in yellow;

locations associated with Pip are marked in green.

Inset: Australia. Magwitch was transported to

Botany Bay, located on the eastern coast of New South Wales just

below Sydney.

Abel Magwitch was probably born in about 1768

(Meckier 158-60). As a small child in Essex, he remembers "thieving

turnips for [his] living" (Ch. 42); as he grew up, he passed in

and out of jails for various offenses. After leaving Kingston Jail

(there are a number of Kingstons in England, but we have assumed

that Magwitch's Kingston is Kingston-on-Thames because of its apparent

proximity to Epsom), he met Compeyson at the Epsom races (Epsom

is southwest of London). Compeyson had a house near Brentford (west

of London), where Magwitch watched Arthur die. Later tried for his

activities with Compeyson, Magwitch was sent to -- and briefly escaped

from -- the Medway Hulks. Thereafter, he was transported to Australia

for life, but came back from Botany Bay to see Pip. He landed in

Portsmouth, and traveled to London.

The imaginary student pursued by the misshapen

creature he had impiously made: Pip feels repulsed by Magwitch,

as Frankenstein was by his creature. Frankenstein, by Mary

Shelley, is a Romantic novel, first published in 1818. It was written

as a result of a contest between the Shelleys (Mary and Percy) and

Lord Byron. The object of the contest was to write the best horror

story, but only Mary Shelley's was completed. Frankenstein, about

a young man who brings a creature to life, only to be horrified

by what he has made, is still popular.

Botany Bay: Botany Bay is a coastal town

in Australia, located just south of Sydney. Magwitch, indicating

that he is "back from Botany Bay" (Ch. 40), identifies his penal

colony as that of New South Wales. There were two Australian penal

colonies in the 19th century (New South Wales and Van Dieman's Land),

as well as smaller colonies in Bermuda and on Norfolk Island (a

volcanic island off the coast of Australia). New South Wales was

by far the largest colony. In 1838, the Select Committee on Transportation

reported that 75,200 convicts had been sent there since its establishment

in 1787 ("Report" 604). In 1840, New South Wales refused to accept

further convicts (Mitchell 502).

Bridewells and Lockups: Bridewell became

the generic name for a prison, but originally referred to Bridewell

Prison in London. The Oxford English Dictionary gives the

following etymology: The original prison was named after St. Bride's

Well -- "a holy well in London, near which Henry VIII had a 'lodging',

given by Edward VI for a hospital, afterwards converted into a house

of correction."

Calendar, the: Pip, contemplating Magwitch,

"would sit and look at him, wondering what he had done, and loading

him with all the crimes in the Calendar" (Ch. 40). The Calendar

refers to the Newgate Calendar, a compilation of "recent

notorious crimes" published between 1770 and 1820. After 1820, similar

publications were occasionally available -- the Newgate Calendar

between 1824 and 1826, and the New Newgate Calendar in 1826

(Meckier 181). The sensational nature of the material in these "Calendars"

made this kind of publication popular, and weekly magazine-like

"Calendars" were also published in the 19th century. Martins'

Annals of Crime; or New Newgate Calendar, and General Record of

Tragic Events, Including Ancient and Modern Modes of Torture was

such a "Calendar." A sort of penny dreadful (the price was literally

"one penny"), it was published in weekly numbers. Each number gave

sensational accounts of crimes, personal histories of criminals,

and descriptions of various kinds of historical punishments. Some

features were ongoing, such as a series on "The Most Notorious Pirates"

or "The Most Notorious Highwaymen," and ran in several consecutive

numbers.

Hair powder, and spectacles, and black clothes

-- and shorts and whatnot: The disguises that Magwitch suggests

for himself are somewhat out of fashion. Hair powder, though extremely

popular in the 18th century, became unfashionable after 1795, when

a tax on its wearers was passed. Given the extreme popularity of

hair powder at the time, it had been estimated that this tax would

produce £210,000 a year (the tax for a year's use of hair powder

being a guinea -- slightly more than a pound). The tax, however,

essentially killed the fashion (Fairholt 328). Shorts, or knee-breeches,

were also somewhat old-fashioned by the time Magwitch thinks of

adopting them. In the last decade of the 18th century, buckskin

knee-breeches (close-fitting trousers that extended to just below

the knee) were considered "immense taste"; afterwards, however,

knee-breeches became less popular, and more formal -- Fairholt notes

that they were "still worn as court dress" (Fairholt 326, 400) in

1860. It may be that the latter association, however -- of knee-breeches

with formality and nobility -- explains Magwitch's "extraordinary

belief in 'shorts' as a disguise" (Ch. 40). They imply gentility,

and Magwitch -- never before a gentleman, and with vague or overstated

ideas of what one looks like -- hopes to disguise himself as such.

Horrors, the: Magwitch relates that "Arthur

was dying ... with the horrors upon him" (Ch. 42), hallucinating

a woman in white. The horrors, according to the Oxford English

Dictionary, refer to a "fit of horror or extreme depression"

especially associated with delirium tremens (a result of

alcoholism).

Measured my head: Magwitch, recalling

that people measured his head when he was in prison growing up,

describes a phrenological examination. Phrenology, a dubious but

popular science of the time, essentially maintained that personal

qualities could be distinguished according to the size and shape

of the head. As the Oxford English Dictionary explains, phrenology

was a "theory originated by [Drs.] Gall and Spurzheim, that the

mental powers of the individual consist of separate faculties, each

of which has its organ and location in a definite region of the

surface of the brain, the size or development of which is commensurate

with the development of the particular faculty; hence, the study

of the external conformation of the cranium as an index to the development

and position of these organs, and thus of the degree of development

of the various faculties." Treatises on phrenology were widely available

at the time Dickens was writing. The Dictionary of Daily Wants

(1858-9) lists 18 books on phrenology (handbooks, manuals, etc.)

and their prices.

Negro-head, loose tobacco: The tobacco

that Magwitch smokes, identified by Pip as "negro-head," was a dark

kind of tobacco used, according to the Dictionary of Daily Wants

(1858-9), almost exclusively for smoking (as opposed to snuff-taking,

chewing, etc.) and was often "manufactured in the form of a thickish

rope" (1006).

Patience: Magwitch plays "a complicated

kind of Patience with a ragged pack of cards of his own" (Ch. 40).

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this is a kind

of solitaire -- "A game of cards (either ordinary playing cards,

or small cards marked with numbers), in which the cards are taken

as they come from the pack or set, and the object is to arrange

them in some systematic order."

Bibliographical

information

|