|

NOTES ON THE NOVEL: ISSUE 17

Printable View

The city maps used to illustrate this issue are

reproduced from Collins' Illustrated Atlas of London, published

in 1854. Pip's London would have been that of the 1820s, and Dickens'

London, at the time he was composing the novel, was that of 1860-1.

Collins' maps thus represent a London that falls between the historical

moment represented in the novel and the historical moment of the

novel's composition.

Since the chapters in this issue (Chs. 54-56)

take place in late 1829 (Meckier 160), the maps used here show a

city that has undergone about 25 years of change since Pip's time.

Nevertheless, they are very useful in tracking Pip's progress through

the city; the reader should merely keep in mind that some of the

landmarks would not have existed in the late 1820s. The most significant

of these are the railway lines marked on the Key Map -- the

railroad did not enter London until the late 1830s and early 1840s

(Tallis's Illustrated London 186-7). The Key Map also

shows a bridge that Pip would not have recognized -- the Hungerford

Bridge between Waterloo and Westminster Bridges. And London Bridge

was, in Pip's time, Old London Bridge -- a different structure,

but built in essentially the same place. (New London Bridge would

have begun construction a few yards from Old London Bridge when

Pip was living in London, but would not have replaced the old bridge

during his tenure [Meckier 162]. Given that both London Bridges

would have been mapped in the same place, the difference between

the bridges makes no difference to our reading of the map.) Any

further discrepancies will be noted where appropriate.

History and features of Collins' Atlas

(1854)

Collins' Atlas was created in response

to the amplified tourist trade in London resulting from the Great

Exhibition of 1851. Previous to the Atlas, maps tended to

be very large and unwieldy, and though large city maps could be

folded up and carried, Collins designed his maps with a specific

view to portability (Dyos 10). The Atlas consists of one

large map of the whole city of London (the Key Map), followed

by 36 plates. The Key Map is drawn with numbered sections,

and these sections are represented in detail by the plates (the

numbers on the Key Map refer to the numbers of the plates).

The chief drawback to the Atlas is that, although the Key

Map keeps North at the top, the plates do not always observe

this convention (Dyos 13). This disregard of the compass, however

puzzling to someone attempting to navigate London in 1854, is in

many respects an advantage for the modern reader: The detailed plates

-- drawn to represent popular views of the city and/or popular routes

through it -- give us a unique view of the sites of Pip's adventures

in 19th century London. Any major discrepancies between the landmarks

shown on the maps and those that Pip would have been acquainted

with (given that the map was composed in 1854, about twenty-five

years after Pip's time in London) will be indicated where appropriate.

A Note on the Illustrations

The engraved illustrations of London reproduced

in this and other issue(s) were prepared as a result of the Great

Exhibition of 1851. Tallis's Illustrated London (published

in 1851-2, in two volumes) was created specifically to commemorate

the Exhibition, and furnishes, not only a great many engravings

of London scenes, but also a long history of, and commentary on,

the sights of London and its environs. Since Tallis's Illustrated

London was published almost 25 years after the events related

in this issue (Chapter 54-56 take place in 1829 [Meckier 160]),

some of the views commemorated in Tallis's would not have

been available to Pip. Only those illustrations that show cityscapes

and landmarks as they would have appeared to Pip in the 1820s have

been included here.

A tour of chapters 54-56

The Key Map of Collins' Atlas, showing

London as a whole, gives a useful overview of the city locations

mentioned in this issue. The London locations described in Chapters

54-56 appear on the Key Map mostly in area 22 (shown in detail

on the corresponding Plate), and eastward down the river Thames,

to Magwitch's hiding place and beyond. In the later chapters, when

Pip takes his walk with Wemmick, he visits the general areas of

Walworth and Camberwell, south of London, at about the lower middle

of the Key Map. All of the maps reproduced here have been

highlighted for convenience of reference and increased legibility.

Plate 22 of Collins' Atlas (below) shows

several of the landmarks noted by Pip early in the escape mission,

before they retrieve Magwitch from his hiding place: "Old London

Bridge was soon passed, and old Billingsgate market with its oyster-boats

and Dutchmen, and the White Tower and Traitor's Gate, and we were

in among the tiers of shipping" (Ch. 54). Billingsgate Market is

visible on Plate 22 just east of Old London Bridge, and the Tower

of London is just east of Billingsgate. Note that the Blackwall

Railway (noted in the caption of Plate 22) would not yet have existed

in 1829.

The "White Tower" is the oldest part of the Tower

of London, built in 1078 -- a "large square irregular building,

standing almost in the center of the inner ward. The summit of the

walls is embattled, and at each angle is an elevated turret rising

considerably above the roof" (Tallis's Illustrated London, vol.

2, 145-6). The White Tower is visible in the illustration of the

Tower of London on Plate 22 of Collins' Atlas (above) --

it is the structure in the middle, with the four turrets. "Traitor's

Gate," also mentioned by Pip, is an entrance on the river side of

the Tower.

Pip and Herbert proceed down the river, pick

up Magwitch, and make for the "long reaches below Gravesend, between

Kent and Essex, where the river is broad and solitary" (Ch. 54)

toward the Mouth of the Thames. They stop at a lonely inn at the

riverside, and Pip sees, from their lodging, men pass "across the

marshes in the direction of the Nore" (Ch. 54). The Nore is a sandbank

"off the Isle of Grain, which terminates the peninsula on which

the Cooling marshes lie, where the [opening of Great Expectations

took] place" (Mitchell 506). Thus, Pip is back in Kent, close

to the place where he first met Magwitch. The Nore is marked on

a map of England and Wales 1660-1891 in Gardiner's School

Atlas of English History. Detail from this map -- enlarged for

clarity -- is given here.

Locations important to the early part of the novel

are also marked on Gardiner's map: The Medway (where the

Hulks docked), Rochester (home of Miss Havisham), and London appear.

Dover, the decoy location to which Magwitch was ostensibly taken

when Herbert hid him at Mill Pond Bank -- "At the old lodgings it

was understood that he was summoned to Dover" (Ch. 45) -- is also

marked on this map, at the lower right.

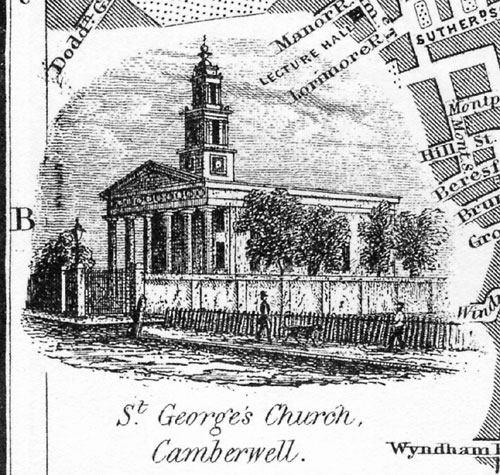

Back in London, after the failure of Magwitch's

escape attempt, Wemmick asks Pip to take a walk with him one Monday

morning. They walk, as it turns out, to Wemmick's wedding: "We went

towards Camberwell Green, and when we were thereabouts, Wemmick

said suddenly, 'Halloa! Here's a church!'" (Ch. 55). Camberwell

Green is not illustrated or marked on Collins' Atlas; however,

it lies east of the intersection of Camberwell Road and Camberwell

New Road, at the bottom of the Key Map. It was well known

at Pip's time, as well as at the time Collins' Atlas was

created: the second biggest metropolitan fair (after Greenwich)

was held there (Tallis's Illustrated London, vol. 2, 78).

The church that is near -- "thereabouts" -- to Camberwell Green

is probably St. George's Church of Camberwell, open since 1824 (Meckier

188). This church, which we have marked in on the Key Map with

a cross (see Key Map above), is south of Albany Road, a bit

to the east of the Green. Collins' Atlas offers this engraved

illustration of St. George's.

Hymen: In Greek mythology, Hymen is the

god of marriage (OED, "Hymen").

The two men who went up into the Temple to

pray: Pip, having recounted Magwitch's death at the end of Chapter

56, invokes the parable of Luke 18:10-13, which reads as follows:

Two

men went up into the temple to pray: the one a Pharisee, and the

other a publican. The Pharisee stood and prayed thus with himself,

God, I thank thee, that I am not as other men are, extortioners,

unjust, adulterers, or even as this publican. I fast twice in

the week, I give tithes of all that I possess. And the publican,

standing afar off, would not lift up so much as his eyes unto

heaven, but smote upon his breast, saying, God be merciful to

me a sinner. I tell you, this man went down to his house justified

rather than the other: for every one that exalteth himself shall

be abased: and he that humbleth himself shall be exalted.

Buttons: Custom's House officers wore

a uniform with buttons (Mitchell 505-6). Thus the Jack of the causeway

-- convinced that the men he saw belonged to the Custom's House

-- insists that they "Chucked 'em [the buttons] overboard. Swallered

'em. Sowed 'em, to come up small salad" (Ch. 54). The Thames River

Police, however, wore no distinct uniform -- "their dress would

appear to be that of the rivermen and seamen of the day" (Cunnington

260).

Coal-whippers: Pip describes seeing "colliers

by the score and score, with the coal-whippers plunging off stages

on deck, as counterweights to measures of coal swinging up" (Ch.

54). A coal-whipper is a person employed moving coal -- "One who

raises coal out of a ship's hold by means of a pulley" (OED,

"coal-whipper") -- or an apparatus for moving coal, attached

to the deck of a vessel. Pip's coal-whippers, given that they are

"plunging off stages on deck," are people.

Galley, four-oared: The Oxford English

Dictionary defines a "galley" as a large open row-boat, like

the kind "formerly used on the Thames by custom-house officers,"

and uses a passage from Chapter 54 of Great Expectations --

"the Jack ... asked me if we had seen a four-oared galley going

up with the tide?" --to illustrate this usage. Though the vessel

in question does not turn out to hold Customs House officers (who

would be looking for smugglers), the Jack of the causeway thinks

it does: "'A Four [-oared galley] and two sitters don't go hanging

and hovering, up with one tide and down with another, and both with

and against another, without there being Custum 'Us at the bottom

of it'" (Ch. 54).

Jack: Pip describes encountering "a grizzled

male creature, the 'Jack' of the causeway" (Ch. 54) at the riverside

inn. The Oxford English Dictionary defines "Jack" as "variously

applied to a serving-man or male attendant, a labourer, a man who

does odd jobs, etc.," and uses the example of the "grizzled male

creature" from Great Expectations to illustrate the usage

of the word.

Mill-weirs: When Pip goes overboard, he

says that he seemed, for an instant, "to struggle with a thousand

mill-weirs and a thousand flashes of light" (Ch. 54). A mill-weir

is a "dam constructed across a stream to interrupt its flow and

raise its level so as to render it available for turning a mill-wheel.

Also the entire area covered by the water held in check by the dam"

(OED, "mill-weir"). Pip's sensation, then, is of approaching

the turbulence of a mill.

Red-book: Herbert is grateful that Clara

"comes from no family ... and never looked into the red book" (Ch.

55) as his mother does. The red book was "A popular name for the

'Royal Kalendar, or Complete ... Annual Register' (published from

1767 to 1893)" (OED, "red book"). It contained, alphabetically,

the names and addresses of the English gentry.

Recorder's Report: The Recorder of London

was "originally a person [usually a judge or magistrate] with legal

knowledge appointed by the mayor and aldermen to 'record' or keep

in mind the proceedings of their courts and the customs of the city,

his oral statement of these being taken as the highest evidence

of fact" (OED, "Recorder"). The Recorder reported to the

Secretary of State about the sentencing of criminals, and could

recommend clemency for those sentenced to execution (Mitchell 499).

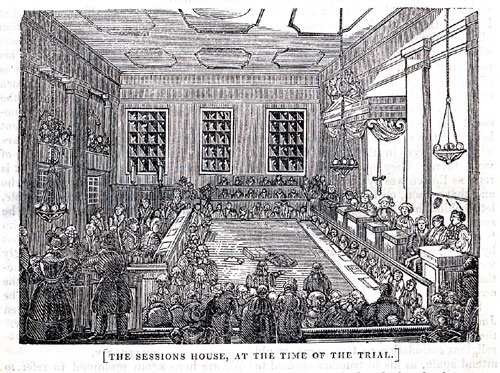

Sessions: Twelve sessions a year, during

which prisoners were put on trial, were held in the Sessions House

in London (Tallis's Illustrated London, vol. 1, 27). Magwitch

comes up for trial in the April session, 1829, and Jaggers attempts

to postpone until the following session -- Trinity term (May 22-June

12). Magwitch, mortally injured during his struggle on the river,

would be unlikely to live so long (Meckier 168). Martin's Annals

of Crime gives us (below) an illustration of the Sessions during

trial.

Thowels: "Thowel" is an obsolete spelling

of "thole," meaning "A vertical pin or peg in the side of a boat

against which in rowing the oar presses as the fulcrum of its action,

[especially] one of a pair between which the oar works; hence, a

rowlock" (OED, "thowel").

Bibliographical

information

|