|

NOTES ON THE NOVEL: ISSUE 2

Printable View

A Note on the Maps:

William Smith's 1815 Map and Delineation of

the Strata of England and Wales with Part of Scotland gives

a detailed account of the geography and geology of most of Great

Britain. It consists of several large maps, each about 16x24 inches,

mounted on canvas. These maps can be folded into smaller squares,

and some of the seams -- where the map folds and the canvas shows

through -- are visible on the sections of the maps reproduced here.

The whole work consists of 16 large maps (a "General Map"

of England, Wales and Scotland, and 15 regional maps), together

with a "Memoir" discussing the geological study they illustrate.

Detail from Map 12, in a reduced size, is reproduced here.

This portion of Smith's 1815 Map and Delineation

of the Strata of England [etc.] (above) shows the area described

in Chapters 5-7 of Great Expectations.

This drawing of England (below) indicates the

portion of the country illustrated by Smith's 1815 Strata map.

My notions of the theological positions to

which my Catechism bound me: A Catechism is "an elementary treatise

for instruction in the principles of the Christian religion, in

the form of question and answer" (OED, "catechism"), which

children memorize as a means to moral instruction. Pip, confessing

the inaccuracy of his ideas concerning "the theological position

to which my Catechism bound me" (Ch. 7), indicates that this exercise

was not entirely effective in his case. He tends to take injunctions

literally, believing, for instance, that the admonition to "walk

in the same all the days of [his] life" meant that he was always

to take the same route through his village.

Mark Antony's oration over the body of Caesar:

In Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, Antony gives the following

speech (III.ii.74-) to the citizens.

Friends,

Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears.

I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him.

The evil that men do lives after them;

The good is oft interrèd with their bones.

So let it be with Caesar. The noble Brutus

Hath told you Caesar was ambitious.

If it were so, it was a grievous fault,

And grievously hath Caesar answered it.

Here, under leave of Brutus and the rest --

For Brutus is an honourable man,

So are they all, all honourable men --

Come I to speak in Caesar's funeral.

He was my friend, faithful and just to me.

But Brutus says he was ambitious,

And Brutus is an honourable man.

He hath brought many captives home to Rome,

Whose ransoms did the general coffers fill.

Did this in Caesar seem ambitious?

When that the poor have cried, Caesar hath wept.

Ambition should be made of sterner stuff.

Yet Brutus says he was ambitious,

And Brutus is an honourable man.

You all did see that on the Lupercal

I thrice presented him a kingly crown,

Which he did thrice refuse. Was this ambition?

Yet Brutus says he was ambitious,

And sure he is an honourable man.

I speak not to disprove what Brutus spoke,

But here I am to speak what I do know.

You all did love him once, not without cause.

What cause withholds you then to mourn for him?

O judgment, thou art fled to brutish beasts,

And men have lost their reason! Bear with me;

My heart is in the coffin there with Caesar,

And I must pause till it come back to me.

Collins' Ode on the

Passions: When Pip "particularly venerate[s] Mr. Wopsle as Revenge,

throwing his blood-stain'd sword in thunder down, and taking the

War denouncing trumpet with a withering look" (Ch. 7), he is giving

an account of a performance of William Collins' 1746 poem, "The

Passions, An Ode for Music." This poem, which apostrophizes ancient

Grecian music (invoking it as a "Heav'nly Maid" (line 1)), is allegorical:

The various passions -- Fear, Anger, Despair, Hope, Revenge, etc.

-- are personified, and gather around Music, insisting upon expressing

themselves ("Each, for Madness rul'd the Hour, / Would prove his

own expressive power" [lines 15-16]). Each Passion makes music according

to its nature, and Revenge -- which Wopsle renders so impressively

-- interrupts Hope:

And

Hope enchanted smil'd, and wav'd Her golden Hair.

And longer had She sung, -- but with a Frown,

Revenge impatient rose,

He threw his blood-stain'd Sword in Thunder down,

And with a with'ring Look,

The War-denouncing Trumpet took,

And blew a Blast so loud and dread,

Were ne'er Prophetic Sounds so full of Woe.

And ever and anon he beat

The doubling Drum with furious Heat;

And tho' sometimes each dreary Pause between,

Dejected Pity at his Side,

Her Soul-subduing Voice applied,

Yet still He kept his wild unalter'd Mien,

While each strain'd Ball of Sight seem'd bursting from his Head.

(38-52)

Crock and dirt: Pip's sister is dismayed

to find him "grimed with crock and dirt" in Chapter 7. Crock is

an obsolete term for "Smut, soot, dirt" (OED, "crock").

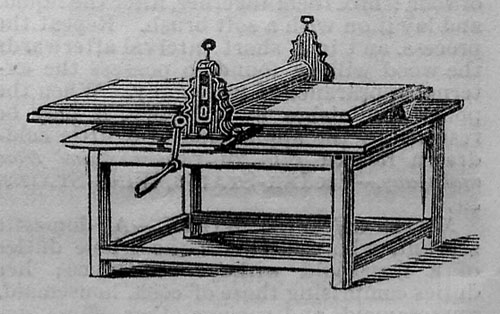

Mangle: Pip describes the hut bedstead

as "like an overgrown mangle without the machinery" (Ch. 5). The

Dictionary of Daily Wants (1858-9) gives an illustration

(below) of a small mangle for household use, and describes the process

of mangling.

MANGLING.

-- A process in connection with the laundry, which is usually

adopted for articles of domestic use, or wearing apparel of a

coarse or plain kind. The articles to be mangled are wrapped round

rollers, and are forced backward and forward under a heavily loaded

case. The art consists chiefly in laying the clothes smoothly

upon the cloth, and in arranging them in such a way that those

of equal substance shall come together, so that the surface may

not be rendered irregular. Most articles are folded two or three

times, and come out better when so arranged than they do when

put in the mangle in single folds. Beyond this, it is only necessary

to roll them evenly on the rollers, and lay them in the mangle.

Articles which have buttons attached to them, are not adapted

for the mangle; when the buttons are made of slender material

they are liable to be crushed, and if made of metal they are apt

to cut the fabrics brought into contact with them, and also to

cause iron-moulds. The ordinary mangle is a machine of large dimensions,

which the premises of a private establishment are sometimes not

large enough to contain. A smaller kind of mangle has been therefore

invented, acting by means of a spring or some other substitute

for mere force of weight. Of these, the mangle shown in the engraving

is the best. It is portable; and the bed on which the linen is

mangled is not a fixture as in the ordinary mangle, but traverses

backward and forward, whilst the roller on which the linen is

placed, remains stationary. The pressure is obtained by means

of springs adjusted by a screw, and the roller is either of metal

or wood. The figure shows the machine placed upon an ordinary

table; but when taken to pieces it consists of the bed, and also

of the roller and works, which may be contained within a box two

feet eight inches long and one foot square. (658)

Market-days: "Mrs. Joe made occasional

trips with Uncle Pumblechook on market-days" (Ch. 7). In rural 19th

century Kent, market days were usually held once or twice a week

(Bagshaw, "Table Showing ... Weekly Market Days"). The market town

in Great Expectations is the town of Rochester, and though

we have not been able to confirm the market-day for Rochester for

the early part of the century, it was on Fridays by mid-century

(Bagshaw, "Table").

Mogul: When Joe tells Pip that he "don't

deny that your sister comes the Mo-gul over us, now and again" (Ch.

7), he is invoking an image of significant foreign power. In the

19th century, according to the OED, "the Great or Grand

Mogul, also shortened to the Mogul [was] the common designation

among Europeans of the emperor of Delhi, whose empire at one time

included most of Hindustan; the last nominal emperor was dethroned

in 1857" (OED, "Mogul"). More generally, mogul (with a small

"m") meant "A great personage; an autocratic ruler" (OED).

Joe's "Mo-gul" probably comprehends both "Mogul" and "mogul."

Purple leptic fit: Joe describes his father's

death as the result of a "purple leptic fit" (Ch. 7), which is his

way of referring to apoplexy -- the malady that we now usually call

a stroke (Merriam-Webster, "apoplectic").

The Dictionary of Daily Wants (1858-9)

describes the disease and its treatments as follows:

APOPLEXY.

-- Apoplexy is a disease which arrests all voluntary motion, and

deprives a person of consciousness, as though he had been struck

by a blow. Sometimes a person is warned of the approach of apoplexy

by various symptoms, such as giddiness, drowsiness, loss of memory,

twitching of the muscles, faltering of the speech, &c.; but most

frequently he falls to the ground without any warning, and lies

as though in a deep sleep. While so lying he breathes heavily,

with a snorting kind of noise, and with considerable muscular

action of the features. The face is red and swollen, the veins

distended, the eyes protruding and blood-shot, remaining half-open

or quite closed, and a foam frequently forms about the mouth.

Apoplexy

arises from accumulation of blood in the system, but it may be

the result of an enfeebled constitution, and general want of vitality.

Where

a person is seized as described, a medical man should be sent

for, and the patient should be carried into a cool room and placed

in a sitting posture, in such a situation that the air may be

freely admitted to him. The neckcloth, shirt collar, waist-band,

and other ligatures should be unfastened, and cold water should

be poured over the head. Mustard plasters may be applied to the

soles of the feet and the calves of the legs, or where the mustard

cannot be immediately procured, the feet and legs should be placed

in hot water.

If

the attack occurs in a person of full habit of body, a

dozen leeches may be applied behind the ears and on the temples.

It is of great importance that the bowels should be freed of their

contents, and as there is a great difficulty of swallowing, one

drop of croton oil should be placed on the tongue and repeated

every two hours, until the object is entirely accomplished. Blood-letting

should in no case by attempted by a non-professional person. Where

the fit arises from enfeebled strength (which is indicated by

a small irregular pulse) the remedies should be of a milder form,

and stimulants may be cautiously administered at intervals. The

most common immediate cause of apoplexy is pressure of

the brain, either from an effusion of blood or serum, or from

a distention of the vessels of the brain by an accumulation of

the blood in them, independently of effusion.

The

predisposing causes are the habitual indulgence of the

appetite in rich and gross food, or stimulating drinks, coupled

with luxurious and indolent habits, sedentary employments carried

to an undue length; the habit of sleeping, especially in a recumbent

posture after a full meal; and lying too long in bed.

The

exciting causes are excesses in eating and drinking, violent

mental emotions; the sudden suppression of piles, gout, rheumatism;

or any other cause which augments the circulation of blood to,

or extracts the flow of blood from the brain.

Persons

below the middle height, robust, with large hands and short thick

necks, are generally recognized as apoplectic subjects; but it

is, in truth, confined to no particular conformation of the body,

all persons being liable to be attacked by it.

Persons,

however, who are predisposed to this disease should not

fail to profit by the warnings of its approach mentioned at the

commencement of this article. Their diet should be light and nutritious;

all luxurious habits should be abandoned, and moderate exercise

should be taken. Above all, they should avoid giving way to their

passions, as it is well known that many persons have been struck

with death in the midst of a fit of anger. (31-2)

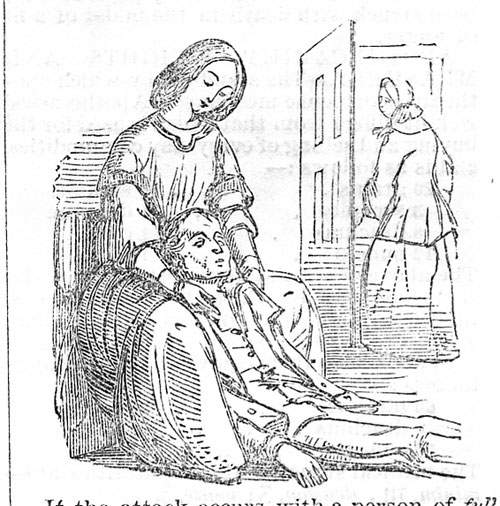

This illustration (below), from the Dictionary

of Daily Wants, shows the treatment appropriate to an apoplectic

fit.

Steam, yet in its infancy: Pip compares

Joe's education to "Steam," indicating that both steam power and

Joe's literacy are "in their infancy" in Chapter 7. Pip is giving

Joe lessons in about December 1813 (Meckier 171), before steam power

became prominent in English industry and transportation. The steam

engine had been developed in the 18th century by Thomas Newcomen,

and improved by James Watt (after whom the unit of power is named);

but it was not widely implemented until the 19th century ("History

of Steam Engines," Inventors.about.com). In 1815 (about two years

after Pip reads with Joe in Chapter 7), steamships first appeared

on the Thames, and the railroad followed somewhat later (Meckier

182). Passenger railroad service began to appear in the 1820s, but

was not widely developed until the 1830s and 1840s ("History of

Railroad Innovations," Inventors.about.com).

Stocks: When the soldiers spit over their

"stocks" into the yard (Ch. 5), they are spitting over the high,

stiff collars of their uniforms (OED, "stock").

Wheelwright: A maker of wheels and wheeled

vehicles (OED, "wheelwright").

Bibliographical

information

|