|

NOTES ON THE NOVEL: ISSUE 5

Printable View

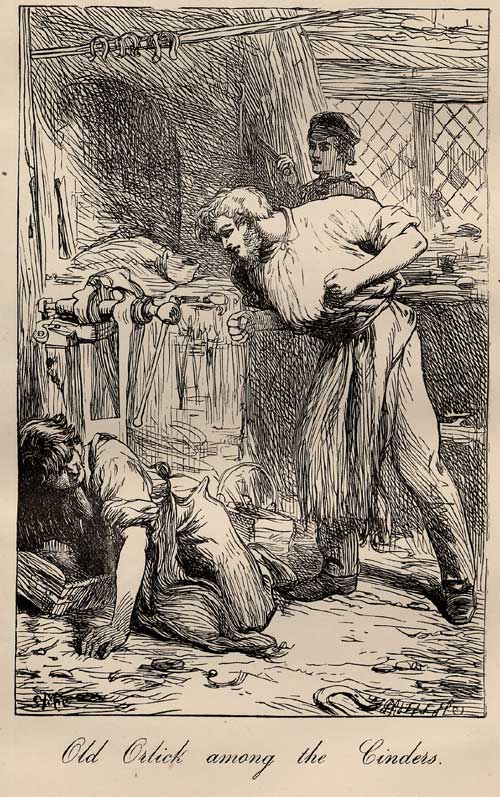

The illustration below, by Marcus Stone, appeared

in the 1862 edition of Great Expectations. The original serial

(1860-1) and the 1861 editions of the novel were not illustrated.

Cain or the Wandering Jew: When Pip says

that Orlick "would slouch out, like Cain or the Wandering Jew, as

if he had no idea where he was going and no intention of ever coming

back" (Ch. 15), he compares Orlick to famous outcast wanderers in

Christian tradition. Cain, a son born to Adam and Eve after the

Fall, killed his brother Abel, and was condemned by God -- "[A]

fugitive and a vagabond shalt thou be in the earth" (Genesis 4:12).

The Wandering Jew was, according to legend, a man who insulted Christ

as he bore the cross to Calvary, and was doomed to walk the earth

until the Second Coming. Versions of the story vary; an early one

has it that the Wandering Jew was a porter belonging to Pontius

Pilate, "who, when they were dragging Jesus from the Judgment Hall,

had struck him on the back, saying 'Go faster, Jesus, why dost thou

linger?', to which Jesus replied, 'I indeed am going, but thou shalt

tarry till I come'" (Oxford Companion 1052).

A perfect Fury: Mrs. Joe, working herself

into a rage, becomes like "One of the avenging deities, ... dread

goddesses [in Greek and Roman mythology] with snakes twined in their

hair, sent from Tartarus to avenge wrong and punish crime" (OED,

"Fury").

George Barnwell: The "affecting tragedy"

in which Wopsle "invested sixpence, with the view of heaping every

word of it on the head of Pumblechook, with whom he was to drink

tea" (Ch. 15), is a play by George Lillo, first produced in 1731.

The "identification of the whole affair with [Pip's] unoffending

self" (Ch. 15) is apparently suggested to Wopsle on account of the

similarity between Pip's condition (as an apprentice) and that of

the title character, George Barnwell. The Oxford Companion to

English Literature summarizes the play as follows: "Based on

an old ballad, it tells the story of an innocent young apprentice,

Barnwell, who is seduced by a heartless courtesan, Millwood. She

encourages him to rob his employer, Thorowgood, and to murder his

uncle, for which crime both are brought to execution, he profoundly

penitent and she defiant. It was frequently performed at holidays

for apprentices as a moral warning" (393). Mr. Wopsle, as the "ill-requited

uncle of the evening's tragedy," who "fell to meditating aloud in

his garden at Camberwell" and, later in the performance, dies there,

is dramatizing the part of the murdered uncle.

From the "Prologue" of George Barnwell:

A

London 'Prentice ruined is our theme,

Drawn from the fam'd old song that bears his name.

We hope your taste is not so high to scorn

A moral tale esteem'd ere you were born;

Which, for a century of rolling years,

Has fill'd a thousand thousand eyes with tears.

If thoughtless youth to warn, and shame the age

From vice destructive, well becomes the stage;

If this example innocence insure,

Prevent our guilt, or by reflection cure;

If Millwood's dreadful crimes, and sad despair,

Commend the virtue of the good and fair;

Tho' art be wanting, and our numbers fail,

Indulge th' attempt, in justice to the tale. (lines 21-34)

Died ... exceedingly game on Bosworth Field,

and in the greatest agonies at Glastonbury: Mr. Wopsle offers

the diversion of several death scenes on the walk home, including

that of Richard the Third, who died anything but "game" on Bosworth

Field: Failing to defeat Richmond (afterwards King Henry VII), who

stages an invasion, Richard III finds himself is a tight spot, unmounted

and vulnerable, and shouts -- famously, in Shakespeare's version

-- "A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!" (V.iv.7). Wopsle's

agonies at Glastonbury are harder to trace. The critical consensus

seems to be that Dickens confuses Glastonbury with Edmundsbury,

where King John dies of poison in Shakespeare's King John (Mitchell

492). There is, in any case, no Glastonbury in Shakespeare.

Bow-street runners: The "Bow-street men

from London" who linger in the house after the attack on Mrs. Joe,

and whom Pip calls "the extinct red-waistcoated police" (Ch. 16),

were a force of London policemen replaced by the Metropolitan Police

in 1829 (the attack on Mrs. Joe would have occurred around 1820)

(Meckier 181). These policemen were called "Bow-street runners"

after the metropolitan police station located on Bow-street, near

Covent Garden, in London (OED, "Bow-street").

Guinea: Miss Havisham's gift of a guinea

to Pip in Chapter 17 is a gift of slightly over a pound (21 shillings,

where 20 shillings equaled a pound). For the significance of this

coin as Miss Havisham's legal tender, see the note on guineas in

Issue 4.

Journeyman: Orlick, whom "Joe [keeps]

at weekly wages" (Ch. 15), is a journeyman -- "One who, having served

his apprenticeship to a handicraft or trade, is qualified to work

at it for ... wages; ... a qualified mechanic or artisan who works

for another. Distinguished on one side from apprentice [like

Pip], on the other from master [like Joe]" (OED, "journeyman").

Alternate definitions of "journeyman" give a more proverbial flavor

-- "One who is not a 'master' of his trade or business"; "One who

drudges for another; a hireling, one hired to do work for another."

Perhaps the condition implied by these alternate definitions is

a contributing factor to Orlick's ill temper.

Newgate: When Pip says that "when Mr.

Wopsle got to Newgate [in his dramatic reading], I thought he never

would go to the scaffold" (Ch. 15), he refers to the trajectory

of prosecution in London: Newgate Prison, part of the complex of

legal buildings in London called the Old Bailey, stood near the

Sessions House, where trials were held. As it is described in Tallis's

Illustrated London (1851-2, vol. 1), its "front occupies nearly

one entire side of the Old Bailey, and extends to Newgate-street,

of which it forms a corner" (27). In the case of conviction and

execution, prisoners were taken from captivity in Newgate and hanged

publicly in front of the Old Bailey.

Small-coal: Small-coal, according to the

OED, refers to charcoal, "small or refuse coal," or slack.

When Pip says he feels "dusty with the dust of small-coal, and [that

he] had a weight upon his daily remembrance to which the anvil was

a feather" (Ch. 14), he recalls the discomfort of his conscience

according to the physical conditions of the forge.

Bibliographical

information

|