|

NOTES ON THE NOVEL: ISSUE 8

Printable View

A Note on the Maps:

The maps used to illustrate this issue are reproduced

from Collins' Illustrated Atlas of London, published in 1854.

Pip's London would have been that of the 1820s, and Dickens' London,

at the time he was composing the novel, was that of 1860-1. Collins'

maps thus represent a London that falls between the historical moment

represented in the novel and the historical moment of the novel's

composition.

Since Pip arrives in London in the summer of

1823 (Meckier 158), the maps used to illustrate this issue show

a city that has undergone about 30 years of change since Pip's time.

Nevertheless, they are very useful in tracking Pip's progress through

the city; the reader should merely keep in mind that some of the

landmarks would not have existed in 1823. The most significant of

these are the railway lines marked on the Key Map -- the

railroad did not enter London until the late 1830s and early 1840s

(Tallis's Illustrated London 186-7). The Key Map also

shows a bridge that Pip would not have recognized -- the Hungerford

Bridge between Waterloo and Westminster Bridges. And London Bridge

was, in Pip's time, Old London Bridge -- a different structure,

but built in essentially the same place. (New London Bridge would

have begun construction a few yards from Old London Bridge when

Pip was living in London, but would not have replaced the old bridge

during his tenure [Meckier 162]. Given that both London Bridges

would have been mapped in the same place, the difference between

the bridges makes no difference to our reading of the map.) Any

further discrepancies will be noted where appropriate.

History and Features of Collins' Atlas

(1854)

Collins' Atlas was created in response

to the amplified tourist trade in London resulting from the Great

Exhibition of 1851. Previous to the Atlas, maps tended to

be very large and unwieldy, and though large city maps could be

folded up and carried, Collins designed his maps with a specific

view to portability (Dyos 10). The Atlas consists of one

large map of the whole city of London (the Key Map), followed

by 36 plates. The Key Map is drawn with numbered sections,

and these sections are represented in detail by the plates (the

numbers on the Key Map refer to the numbers of the plates).

The chief drawback to the Atlas is that, although the Key

Map keeps North at the top, the plates do not always observe

this convention (Dyos 13). This disregard of the compass, however

puzzling to someone attempting to navigate London in 1854, is in

many respects an advantage for the modern reader: The detailed plates

-- drawn to represent popular views of the city and/or popular routes

through it -- give us a unique view of the sites of Pip's adventures

in 19th century London. Any major discrepancies between the landmarks

shown on the maps and those that Pip would have been acquainted

with (given that the map was composed in 1854, about thirty years

after Pip's tenure in London) will be indicated where appropriate.

A Note on the Illustrations

Like Collins' Atlas, the engraved illustrations

of London reproduced in this and subsequent issue(s) were prepared

as a result of the Great Exhibition of 1851. Tallis's Illustrated

London (published in 1851-2, in two volumes) was created specifically

to commemorate the Exhibition, and furnishes, not only a great many

engravings of London scenes, but also a long history of, and commentary

on, the sights of London. Since Tallis's Illustrated London was

published, like Collins' Atlas, about 30 years after Pip's

tenure in the city, some of the views commemorated in Tallis's

would not have been available to Pip. Thus, only those illustrations

that show cityscapes and landmarks as they would have appeared to

Pip in the 1820s have been included here.

A tour of Chapters 23-26: Pip's early experiences

in London

The Key Map of Collins' Atlas, showing

London as a whole, gives a useful overview of Pip's progress in

this issue. All of the maps reproduced here have been highlighted

for convenience of reference and increased legibility.

Chapters 23-26 of Great Expectations occur

in the areas marked on the Key Map by numerals 1, 2, and

33/34, as well as in Hammersmith, which is to the west of London

and thus beyond the bounds of Collins' Atlas.

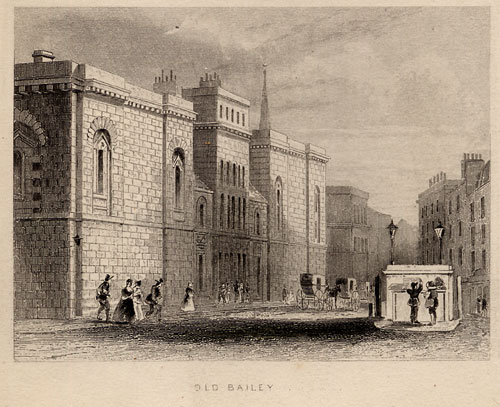

When Wemmick speaks of "getting evidence together

for the Bailey" (Ch. 24), he is preparing for trial. The Old Bailey,

visible on Plate 1 of Collins' Atlas (below) in the lower

left corner, is the street in which Newgate Prison and the Sessions

House stand -- the latter named for the twelve "sessions" held yearly

for the trial of prisoners (Tallis's Illustrated London,

vol. 1, 25-7).

The Sessions House is located, on Plate 1, at

the top of Old Bailey, at the corner of Ludgate Hill. As indicated

previously, Hungerford Bridge, which appears on this Plate, would

not have existed during Pip's time in London.

Tallis's Illustrated London gives illustrations

of both the Sessions House and the Old Bailey.

Wemmick invites Pip to visit him in Walworth,

and the two walk from the office (in Little Britain, near Smithfield)

to Wemmick's home. Walworth at that time (1823) was a sort of developing

suburb, and though Pip does not specify where in Walworth Wemmick

lives, the walk from Jaggers' office to Wemmick's domestic "castle"

would take them south over the Thames, probably via Blackfriars

or Southwark Bridge. The district of Walworth, visible on the Key

Map (see Key Map again above), lies to either side of

Walworth Road. Having undergone significant development between

1823 (when Pip visits for the first time) and 1854 (when the map

was drawn), the plates of Collins' Atlas give a very different

view of Walworth than Pip probably would have had. For instance,

Surrey Gardens, just visible to the left of Walworth Road on the

Key Map, was not opened until 1831 (Tallis's, vol.

2, 240).

Pip dines at Jaggers' residence in Gerrard Street,

Soho (Ch. 26). Gerrard Street, near Piccadilly, is visible on Plate

2 of Collins' Atlas (below), at the bottom left.

I had been to see Macbeth at the theatre ...

her face looked to me as if it were all disturbed by fiery air,

like the faces I had seen rise out of the Witches' caldron:

Pip remembers a scene from Shakespeare's Macbeth, in which

the "weird sisters" -- three witches -- are boiling a potion in

their cauldron. Macbeth comes to them to know his future in Act

IV, scene 1, and is warned by three apparitions -- an "armed head,"

a "bloody child," and a "child crowned with a tree in his hand"

-- which rise from the cauldron, speak to him, and descend into

it again.

Britannia metal: Mr. Jaggers, instead

of keeping silverware, furnishes himself with utensils made of Britannia

metal. The Dictionary of Daily Wants (1858-9) describes this

substance as follows:

BRITANNIA

METAL. -- An alloy composed of block tin, antimony, copper, and

brass. It takes a high polish, does not readily tarnish; and when

kept perfectly bright, nearly approaches the luster of silver.

It is not acted upon by acids, and may be safely used in the preparation

or the partaking of food. A number of domestic utensils are made

from this metal, and their cost being very moderate, they are

brought within the reach of nearly all persons. (201)

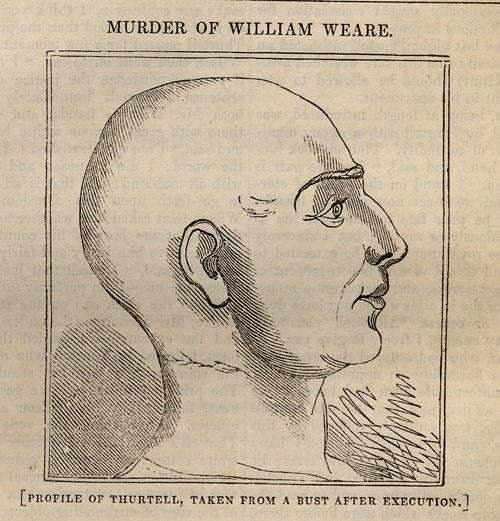

Cast ... made in Newgate: Plaster death-masks

of criminals were frequently made after their execution. According

to Charlotte Mitchell, the Romantic writer Thomas de Quincy "mentions

in the notes to his essay 'On Murder Considered as One of the Fine

Arts' that he was able to buy a plaster cast of the 1811 Ratcliffe

Highway murderer, John Williams" (496). These casts, commercially

available, were apparently created with a popular audience in mind:

Though not nearly as grisly as the two busts Jaggers has in his

offices, the etching below of the "Profile of Thurtell, Taken from

a Bust After Execution" (reproduced from an April 1837 issue of

Martin's Annals of Crime or New Newgate Calendar) corroborates

the practice of commemorating the criminal dead in this fashion.

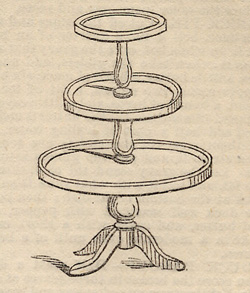

Dumb-waiter: Mr. Jaggers uses a dumb-waiter

at dinner, such that he can keep "everything under his own hand,

and [distribute] everything himself" (Ch. 26). The Dictionary

of Daily Wants (1858-9) gives the following illustration and

description of a dumb-waiter:

DUMB

WAITER. -- A well-known piece of furniture formerly much in use,

and extremely convenient; the shelves should be made to turn round,

which renders them still more serviceable. (390)

Dutch doll: A Dutch doll is a jointed

wooden doll (OED, "Dutch doll") -- hence the comparison of

one of the Pocket children to this kind of doll: "Flopson, by dint

of doubling the baby at the joints like a Dutch doll, then got it

safely into Mrs. Pocket's lap..." (Ch. 23).

Dying Gladiator: Although properly the

Dying Gaul, the statue to which Mr. Pocket is compared in

Chapter 23 -- the Dying Gladiator -- is a Roman copy of a

Greek statue housed in the Museo Capitolino in Rome (Gardner 176-7).

This statue was popular with the 19th century literary imagination

-- it appears (as the "Dying Gladiator") in Henry James' Portrait

of a Lady and Nathaniel Hawthorne's Marble Fawn, as well

as in Great Expectations. The statue is dated c. 230-220

B.C., and is about 36 1/2 inches high (Gardner 176). A picture of

the Dying Gaul/Gladiator is reproduced here by permission

of AICT.

Courtesy of AICT/(Alan

T. Kohl)

Gold Repeater: Jaggers' watch, which Wemmick

asserts is "worth a hundred pounds if it's worth a penny" (Ch. 25),

is a watch that "chimes the last hour when pressed, and thus may

be consulted in the dark" (Mitchell 497).

Grinder: A grinder is a kind of tutor

-- "one who prepares pupils for examination; a crammer" (OED,

"grinder"). According to Pip, Mr. Pocket, "[a]fter grinding

a number of dull blades -- of whom it was remarkable that their

fathers, when influential, were always going to help him to preferment,

but always forgot to do it when the blades had left the Grindstone

-- ... had wearied of that poor work and had come to London" (Ch.

23). The term "grinder" seems to encourage, if indeed it was not

formulated in, jest: A contemporary usage recorded in the OED

from Thackeray runs as follows: "She sent me down here with a grinder:

she wants me to cultivate my neglected genius."

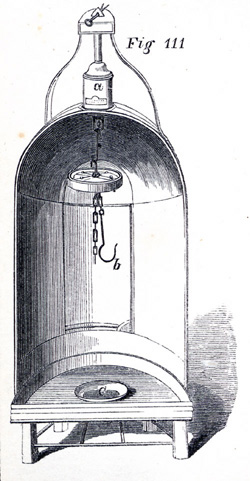

Roasting-jack: A roasting-jack is a "contrivance

for turning meat, etc., while it is being roasted" (OED,

"roasting-jack"), and the "brazen bijou over the fireplace" to which

it is attached in Wemmick's home (Ch. 25) would be a decorative

fixture in brass. Given the size of Wemmick's house (small), and

the configuration suggested by Pip's description of the roasting

jack, the specific machine in question is probably a "bottle-jack."

Walsh's Manual of Domestic Economy (1858) illustrates several

roasting apparatuses, and makes the following remarks on roasting

and bottle-jacks:

FOR

ROASTING OR BAKING, the kind of grate is of the utmost importance:

it being impossible without a good one to turn out a well-dressed

joint to advantage. It may be said that an open fire will always

dress a joint of meat; and so it will, but not a large or small

one at the choice of the cook, unless the fire is capable of being

made narrow or broad, shallow or deep, according to the shape

of the joint and its mode of suspension....

A SPIT OR HOOK for suspending the meat, with some kind of machinery

for turning it, is the next in importance to the fire.... [Such

an implement for suspending and turning the meat is] the bottle-jack

(fig. 111a), which, by means of common clock-work, keeps

up a constant revolution of any article attached to the hook (b).

The objection to this kind [of jack] is that a fire can with difficulty

be made equally strong at the top and bottom, and, consequently,

the joint is roasted either too much or too little in one or other

of its ends. But being of a comparatively low price it is often

used, and succeeds well enough for poultry, game, or small joints....

(445)

A picture of the bottle-jack (fig 111)

from Walsh's Domestic Economy:

Tobacco-stopper: According to the OED,

a tobacco-stopper is "a contrivance for pressing down the tobacco

in the bowl of a pipe while smoking."

Woolsack, or ... mitre: When Pip remarks

of Matthew Pocket that, "in the first bloom of youth, [he had] not

quite decided whether to mount the Woolsack or to roof himself with

a mitre" (Ch. 23), he refers to two prospective professions for

Mr. Pocket: The woolsack is associated with the seat-cushioning

in the House of Lords, and specifically with the Lord Chancellor.

According to the OED, the woolsack is "A seat made of a bag

of wool for the use of judges when summoned to attend the House

of Lords (in recent practice only at the opening of Parliament);

also, the usual seat of the Lord Chancellor in the House of Lords,

made of a large square bag of wool without back or arms and covered

with cloth. Often allusively with reference to the position

of the Lord Chancellor as the highest judicial officer; hence, the

woolsack, the Lord-Chancellorship; on the woolsack, in

this office." The mitre, on the other hand, was a priest's headdress

(OED, "mitre").

Bibliographical

information

|