|

NOTES ON THE NOVEL: ISSUE 9

Printable View

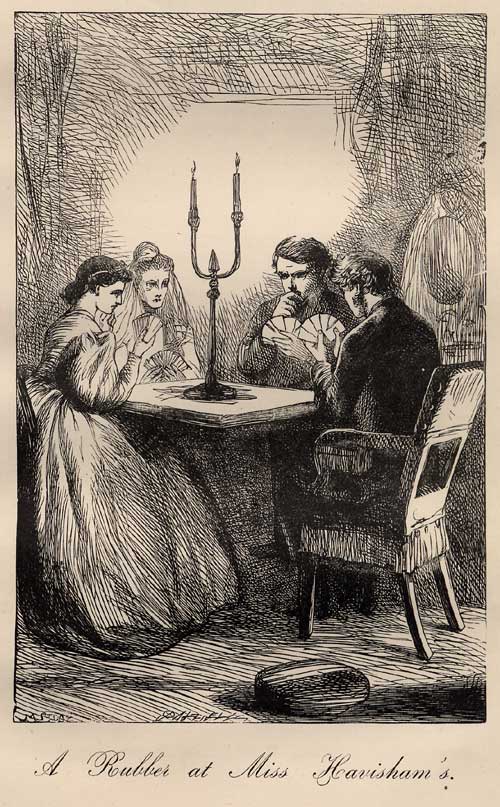

The illustration below, by Marcus Stone, appeared

in the 1862 edition of Great Expectations.

The original serial (1860-1) and the 1861 editions

of the novel were not illustrated. A "rubber" is, "in various games

of skill or chance, a set of (usually) three games, the last of

which is played to decide between the parties when each has gained

one; hence, two games out of three won by the same side" (OED,

"rubber").

Roscian renown ... our National Bard:

Quintus Roscius Gallus was a famous Roman actor (OED, "Roscian");

England's National Bard was, of course, Shakespeare.

Blacking Ware'us: When Pip asks Joe whether

he has seen the sights of London yet, Joe returns the assurance

that he and Wopsle "went off straight" to the Blacking Warehouse

(Ch. 27). This is a submerged allusion to a landmark in Dickens'

own youth. Though for years Dickens told no one about his childhood

experience of working at Warren's Blacking (which manufactured shoe-blacking

at 30, Strand, in London), he makes passing reference to it here,

in Great Expectations, and fictionalizes the experience in

Chapter 11 of David Copperfield. When Dickens' father was

committed for debt to Marshalsea Prison, Dickens was forced to go

to work -- at 12 years old -- at the blacking factory. His job was

to paper the pots of blacking. His place in the factory was offered

by a relation, and lost (to his immense relief) when that relation

quarreled with his father. The following account, which has come

to be known as the "Autobiographical Fragment," was composed by

Dickens for his friend and biographer, John Forster. The "Fragment"

runs partly as follows, and can be found in full in the second chapter

of Forster's Life of Charles Dickens:

Its

[the blacking manufactory's] chief manager, James Lamert, the

relative who had lived with us in Bayham-street, seeing how I

was employed from day to day, and knowing what our domestic circumstances

then were, proposed that I should go into the blacking warehouse,

to be as useful as I could.... [T]he offer was accepted very willingly

by my father and mother, and on a Monday morning I went down to

the blacking warehouse to begin my business life.

It

is wonderful to me how I could have been so easily cast away at

such an age. It is wonderful to me, that, even after my descent

into the poor little drudge I had been since we came to London,

no one had compassion enough on me -- a child of singular abilities,

quick, eager, delicate, and soon hurt, bodily or mentally -- to

suggest that something might have been spared, as certainly it

might have been, to place me at any common school. Our friends,

I take it, were tired out. No one made any sign. My father and

mother were quite satisfied....

No

words can express the secret agony of my soul as I sunk into this

companionship [that of the blacking factory]; and felt my early

hopes of growing up to be a learned and distinguished man, crushed

in my breast. The deep remembrance of the sense I had of being

utterly neglected and hopeless; of the shame I felt in my position;

of the misery it was to my young heart to believe that, day to

day, what I had learned, and thought, and delighted in, and raised

my fancy and my emulation up by, was passing away from me, never

to be brought back any more; cannot be written. My whole nature

was so penetrated with the grief and humiliation of such considerations,

that even now, famous and caressed and happy, I often forget in

my dreams that I have a dear wife and children; even that I am

a man; and wander desolately back to that time of my life....

I

was so young and childish, and so little qualified -- how could

I be otherwise? -- to undertake the whole charge of my existence,

that, in going to Hungerford-stairs of a morning, I could not

resist the stale pastry put out at half-price on trays at the

confectioners' doors in Tottenham-court-road; and I often spent

in that, the money I should have kept for my dinner. Then I went

without my dinner, or bought a roll, or a slice of pudding. There

were two pudding shops between which I was divided, according

to my finances. One was in a court close to St. Martin's-church

(at the back of the church) which is now removed altogether. The

pudding at that shop was made with currants, and was rather a

special pudding, heavy and flabby; with great raisins in it, stuck

in whole, at great distances apart. It came up hot, at about noon

every day; and many and many a day did I dine off it.

We

had half-an-hour, I think, for tea. When I had money enough, I

used to go to a coffee-shop, and have half-a-pint of coffee, and

a slice of bread and butter. When I had no money, I took a turn

in Covent-garden market, and stared at the pine-apples....

I

know I do not exaggerate, unconsciously and unintentionally, the

scantiness of my resources and the difficulties of my life. I

know that if a shilling or so were given me by any one, I spent

it in a dinner or a tea. I know that I worked, from morning to

night, with common men and boys, a shabby child. I know that I

tried, but ineffectually, not to anticipate my money, and to make

it last the week through; by putting it away in a drawer I had

in the counting-house, wrapped into six little parcels, each parcel

containing the same amount, and labeled with a different day.

I know that I have lounged about the streets, insufficiently and

unsatisfactorily fed. I know that, but for the mercy of God, I

might easily have been, for any care that was taken of me, a little

robber or a little vagabond.... But I kept my own counsel, and

I did my work. I knew from the first, that if I could not do my

work as well as any of the rest, I could not hold myself above

slight and contempt....

From

that hour until this at which I write, no word of that part of

my childhood which I have now gladly brought to a close, has passed

my lips to any human being. I have no idea how long it lasted;

whether for a year, or much more, or less. From that hour, until

this, my father and my mother have been stricken dumb upon it.

I have never heard the least allusion to it, however far off and

remote, from either of them. I have never, until I now impart

it to this paper, in any burst of confidence, with any one, my

own wife not excepted, raised the curtain I then dropped, thank

God....

Mentor of our young Telemachus: When Athena

sought to act as an advisor to Odysseus' son, Telemachus, she appeared

in the guise of an Ithacan noble called Mentor. The word "mentor"

thus refers to one who counsels and advises (OED, "Mentor").

Quintin Matsys was the BLACKSMITH of Antwerp:

The paper that is exhibited to Pip at the Blue Boar in Chapter 29

compares Pip to Quintin Matsys -- in a variant spelling, Quentin

Massys -- a famous Flemish painter (1466-1530) who began (like Pip)

as a blacksmith. Matsys' story was popularized by Pierce Egan the

Younger (author of a version of Robin Hood, among other works)

in the 19th century. The title of that work is Quentin Matsys,

the Blacksmith of Antwerp: A Historical Romance.

VERB. SAP.: Short for verbum satis

sapienti, Verb. Sap. is an abbreviated form of a Latin proverb,

"a hint is enough to the wise" (Mitchell 498).

Bread-poultice, baize, rope-yarn and hearthstone:

The aroma of the convicts, including a flavor of bread-poultice,

is composed partly of a medicinal compress made of bread and water

"and spread upon muslin, linen, or other material, applied to the

skin to supply moisture or warmth, as an emollient for a sore or

inflamed part, or as a counter-irritant" (OED, "poultice").

Charlotte Mitchell suggests that this is a pejorative allusion to

the quality of prison rations (498). Baize is a coarse wool, of

which the convict's clothes are made; rope-yarn refers to the strands

of material of which rope is composed (associated particularly with

the ropes of old ships, which could be picked apart and recycled);

and hearthstone is a mix of "powdered stone and pipeclay ... used

to whiten hearths, door-steps, etc." (OED, "baize," "rope-yarn,"

"hearthstone"). Mitchell attributes the scents of rope-yarn and

hearthstone to the labor required of convicts at docks or quarries.

Ha'porth: When the convict on the coach

avers that Pip's convict, from whom he carried the two one-pound

notes for Pip, knew him "not a ha'porth" (Ch. 28), he uses an expression

meaning an insignificant quantity. Ha'porth or ha'p'orth are contractions

of "halfpennyworth" -- a very small amount (OED, "ha'porth").

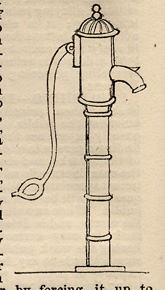

Pump: Pip describes Joe's handshake as

follows: "[H]e caught both my hands and worked them straight up

and down, as if I had been the last-patented Pump" (Ch. 27). The

Dictionary of Daily Wants (1858-9) illustrates the sort of

mechanism invoked, and gives the following description of the technology

of 19th century pumps:

PUMP.

-- An implement for forcing water, indispensable in domestic and

rural economy. For the latter, the most suitable kind of pump

is that shown in the engraving, which according to the bore, or

diameter, may be had at various prices...; the total price depending

on the length of the tube required to reach the bottom of the

well. The operation of the common forcing pump consists in a suction

pipe descending into a well, tank, &c., containing water, and

having in it a valve opening upwards. The piston, or working barrel,

contains a solid piston without any valve, moved up and down by

the rod. Siebe's rotary is found very convenient, either for raising

water from a tank or well, or by forcing it up to any height.

This pump operates by the rotation of a roller on its axis, having

paddles or pistons, by which, when the roller is turned, a vacuum

is produced within the barrel. In consequence of this vacuum the

water flows up a rising break into the barrel; and as the paddles

go round they force it into an opening, which conducts it wherever

it may be wanted, and by that means produces a continuous stream.

By having an ascending tube, the water may be forced to any height;

and by having a horizontal tube with a cock, it may be let out

at pleasure as in a common pump. By having several pipes branching

from the ascending tube, as many cisterns or reservoirs may be

supplied. (812)

Sweep: When Pip describes Barnard's Inn

as "shedding sooty tears outside the window, like some weak giant

of a Sweep" (Ch. 27), he invokes the image of a chimney-sweeper

-- one who cleans soot out of chimneys. Chimney-sweepers, however,

were probably never "giant." Children were frequently employed as

sweeps, because they could -- more readily than full-grown people

-- fit into the small spaces associated with their vocation. Their

advertising cry was "chimney-sweep!" (OED, "chimney sweep"),

but the rhyme of this cry with "weep," together with the hardships

of this kind of labor, has suggested the weeping chimney sweep to

more than one literary imagination: In William Blake's Songs

of Innocence and Experience (1794), for instance, the cry is

thematic: "When my mother died I was very young, / And my father

sold me while yet my tongue, / Could scarcely cry weep weep weep

weep, / So your chimneys I sweep & in soot I sleep" (from "The Chimney

Sweeper" in Songs of Innocence). The corresponding song in

Songs of Experience runs in part, "A little black thing among

the snow: / Crying weep, weep, in notes of woe! / ... / Because

I was happy upon the heath. / And smil'd among the winters snow:

/ They clothed me in the clothes of death. / And taught me to sing

the notes of woe" ("The Chimney Sweeper").

Wicket-keeping: Joe's attention to his

hat, which is continually falling off the mantelpiece (Ch. 27),

is compared to wicket-keeping. A wicket is a feature of a cricket

match, and the wicket-keeper stands behind it, to catch the ball

if it passes the wicket, and to put the cricket-batter "out" if

possible. A wicket is composed of a "set of three sticks called

stumps, fixed upright in the ground, and surmounted by two

small pieces of wood called bails... , forming the structure

(27 x 8 in.) at which the bowler aims the ball, and at which (in

front and a little to one side of it) the batsman stands to defend

it with the bat. (The wicket formerly consisted of two stumps and

one long bail, forming a structure one foot high by two feet wide)"

(OED, "wicket"). The wicket-keeper aims to put the batsman

out "by dislodging a bail (or knocking down a stump) with the ball

held in the hand, at a moment when he is out of his ground" (OED,

"wicket-keeper"). Given that Joe is trying to keep his hat from

tumbling, the hat probably figures, in this little Dickensian allegory,

as the ball -- not the bail.

Whist: Whist (which Miss Havisham, Jaggers,

Estella, and Pip play in Chapter 29, and during which Jaggers, according

to Pip, "took our trumps into custody, and came out with mean little

cards at the ends of hands, before which the glory of our Kings

and Queens was utterly debased") is a card game for four people.

Pigott's New Hoyle; or, The General Repository of Games: Containing

Rules and Instructions for Playing Whist, Piquet, [etc.] (1794)

gives the following description of the game, its rules, and its

peculiar terminology.

THE

GAME OF WHIST.

The game of whist is played by four persons, with fifty-two cards;

the partners are settled by cutting the cards, and the two highest

play against the two lowest. The person cutting the lowest (which

is an ace in cutting) is entitled to deal.

Each

person has a right to shuffle the cards before the deal, and the

elder hand ought to shuffle them last, excepting the dealer.

The

deal is made by having the pack cut by the right-hand adversary,

and the dealer is to distribute the cards, one at a time, to each

of the players, beginning with the left-hand adversary, till he

comes to the last card, which he turns up, being the trump, and

leaves it on the table till the first trick is played.

No

one, before his partner plays, may inform him that he has, or

has not, won the trick; even the attempt to take up a trick, though

won before the last partner has played, is deemed very improper.

No intimations of any kind, during the play of the cards, between

partners, are to be admitted. The mistake of one party is the

game of the adversary: however, there is one exception to this

rule, which is in the case of a revoke; if a person happens not

to follow suit, or trump a suit, the partner is indulged to make

inquiry of him, whether he is sure he has none of that suit in

his hand: this indulgence must have arisen from the severe penalties

annexed to revoking, which affect the partners equally, and it

is not universally admitted.

The

person on the dealer's left-hand is called the elder hand, and

plays first; and whoever wins the trick becomes elder hand, and

plays again; and so on, till all the cards are played out. The

tricks belonging to each party should be turned and collected

by the respective partner of whoever wins the first trick in every

hand. The ace, king, queen, and knave of trumps, are called honours;

and when either of the parties has in his own hand, or between

himself and his partner, three honours, they count two points

towards the game; and in case they should have the four honours,

they count four points.... [Points are] gained by honours and

tricks -- and ten constitute the game. (1-3)

Bibliographical

information

|