NOTES ON THE NOVEL: ISSUE 4

MAPS & ILLUSTRATIONS

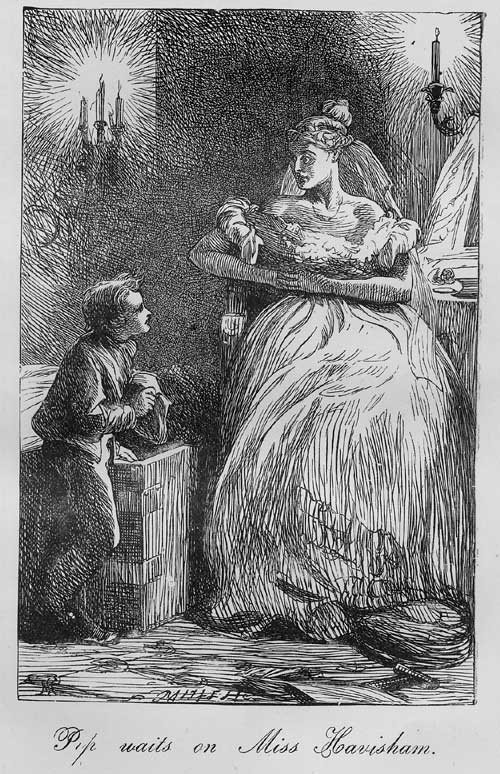

The illustration below, by Marcus Stone, appeared in the 1862 edition of Great Expectations. The original serial (1860-1) and the 1861 editions of the novel were not illustrated.

ALLUSIONS

Myrmidons of justice: The original Myrmidons were the followers of Achilles during the Trojan War. Pip uses the term "myrmidon" in its more modern, pejorative sense, to refer to a regular policemen (OED, "myrmidons of justice").

Old Clem: St. Clement (Old Clem) is the patron saint of anchor-smiths and blacksmiths. He was martyred in about 100 A.D., when he was thrown into the Black Sea with an anchor around his neck. His feast day, November 23, was once celebrated by smiths; activities included exploding gunpowder on the anvil and holding a feast known as Clem Feast ("Clementine traditions," www.s-clements.org).

Young Rantipole: Though Rantipole was a nickname for Napoleon III (1808-73), since Mrs. Joe calls Pip a "young Rantipole" (Ch. 13) in about 1819 (Meckier 173), the name is probably used in its generic sense, meaning an ill-behaved person (Mitchell 490).

Collins' ode: Wopsle makes a repeat performance, in Chapter 13, of William Collins' "The Passions, an Ode for Music": "[I]n the evening Mr. Wopsle gave us Collins' ode, and threw his blood-stain'd sword in thunder down." For additional information and an excerpt, see the note on Collins' Ode in Issue 2.

GLOSSARY OF HISTORICAL THINGS & CONDITIONS

Beaver bonnet: When Mrs. Joe walks to town with Pip, "leading the way in a very large beaver bonnet" (Ch. 13) on the day Miss Havisham has asked to see her husband, she is wearing a bonnet made of beaver fur, either actual or imitation (OED, "beaver bonnet"). The Dictionary of Daily Wants (1858-9) makes the following remarks about bonnets:

BONNET. -- This article of female attire is one of the most important, for, according as it offends against, or conforms with, certain principles of taste, so it is rendered what is called "becoming" or "unbecoming" and materially influences, not only the appearance of the face of the wearer, but the whole person. (166)

Bride cake: Wedding cakes in the early 19th century were not as elaborate as wedding cakes today. As Charlotte Mitchell notes, "the modern wedding cake with tiers did not become fashionable until the late nineteenth century, and Miss Havisham's cake, though raised on an epergne, or stand, would have been simply a large round fruit cake with white icing" (490).

The Dictionary of Daily Wants (1858-9) gives the following recipe and instructions for bride cake:

BRIDE CAKE. -- Take four pounds of flour well dried, four pounds of fresh butter, two pounds of loaf sugar, a quarter of an ounce of mace, and the same of nutmeg. To every pound of flour put eight eggs and four pounds of currants, which have been well washed and picked, and dried before the fire until they have become plump. Blanch a pound of sweet almonds, and cut them lengthwise, very thin; a pound of candied citron, the same of candied orange, and the same of candied lemon-peel, together with half a pint of brandy. First work the butter to a fine cream with your hand, then stir in the sugar for a quarter of an hour, beat the whites of the eggs to a strong froth, and mix them with the sugar and butter; beat the yolks of the eggs for half an hour, and mix them well with the rest; then by degrees put in the flour, mace, and nutmeg, and continue beating the whole till the oven is ready, put in the brandy, currants, and almonds lightly; tie three sheets of paper round the bottom of the hoop, to secure the mixture, and rub it well with butter, put in the cake, and lay the sweetmeats in three layers, with some cake between each layer; as soon as it rises and colours, cover it with paper before the oven is closed up, and bake it for three hours. It may be iced or not, as desired.

[Ingredients:] Flour, 4 lbs.; butter, 4 lbs.; sugar, 2 lbs.; mace, 1/4 oz.; nutmeg, 1/4 oz.; eggs, 32; currants, 16 lbs.; almonds, 1 lb.; candied citron, 1 lb.; candied lemon-peel, 1 lb.; candied orange-peel, 1 lb.; brandy, 1/2 pint. (199)

Garden chair: A garden-chair is, according to the OED, "a wheel or bath chair" or a "chair intended for use in the garden." A bath chair is "a large chair on wheels for invalids" (OED, "bath chair") and the Dictionary of Daily Wants (1858-9) describes it as follows:

A species of small carriage drawn by the hand, especially adapted for invalids, cripples, and aged persons. The peculiar construction of the bath chair admits of its being brought into the hall or even the room, so that a person may be placed comfortably in it, without being exposed to the cold. It may also be drawn round a garden-walk, or on a lawn, enabling a person to have the advantage of carriage exercise within sight of his own home. It should also be remembered that bath chairs are privileged to enter on any public parks and gardens from which carriages drawn by horses are excluded. Bath chairs, together with men to draw them, are generally let out on hire at livery stables. (106)

The garden-chair in which Pip wheels Miss Havisham must be similar to such a conveyance, except that he pushes it from behind ("I saw a garden chair -- a light chair on wheels, that you pushed from behind" [Ch.12]); and, of course, Miss Havisham's garden chair is only used indoors.

Great Seal of England: The Great Seal, according to the OED, is the "seal used for the authentication of documents of the highest importance issued in the name of the sovereign." The Great Seal of England is kept in the custody of the Lord High Chancellor (OED, "Great Seal"). Queen Victoria, the sovereign at the time Dickens was writing Great Expectations (she reigned from 1837 to 1900), went through four Great Seals -- when a seal wore out, it had to be re-engraved (see http://www.royalinsight.gov.uk/200108/focus/gallery.html for further information and pictures of past Seals). A Great Seal typically had a frontal image of the monarch on one side, and a profile of the monarch, often on horseback, on the obverse. Given that Mrs. Joe would have been going to town with her basket in about 1819, when the monarch was still male, Dickens may be invoking the Victorian Seal. (The comparison of Mrs. Joe marching to town with her basket may be more apt if the Seal to which her basket is compared is that of a royal lady, because a monarch's seal would show a picture of him- or herself). In any case, Mrs. Joe apparently carries her basket -- "like the Great Seal of England in plaited straw" (Ch. 13) -- with great stateliness.

Guineas: When Miss Havisham gives Pip a premium of 25 guineas, she uses a coin that, although still legal tender, was no longer minted after 1813, and was out of circulation by 1817 (it is about 1819 when Joe and Pip visit her in Chapter 13). The critical consensus about this donation seems to be that Miss Havisham, reclusive since the turn of the century, would be drawing on an old supply of coins, and unaware that the guinea was no longer in regular circulation (Meckier 184). The guinea was a gold coin, issued first in 1663; though worth 20 shillings (one pound) initially, after 1717 it was worth slightly more than a pound -- 21 shillings (OED, "guinea").

Hardbake: When Pip regards the "black portraits on the walls [of the Town Hall] as a composition of hardbake and sticking-plaister" (Ch. 13), he invokes an image partly confectionary, and partly pharmaceutical: Hard-bake is "A sweetmeat made of boiled sugar or treacle with blanched almonds; 'almond toffee'" (OED, "hard-bake"), and a sticking-plaister is "An external curative application, consisting of a solid or semi-solid substance spread upon a piece of muslin, skin, or some similar material, and of such nature as to be adhesive at the temperature of the body; used for the local application of a medicament, or for closing a wound, and sometimes to give mechanical support" (OED, "plaister" -- see the note on "plaister" in Issue 1 for more detailed information).

Pattens, a spare shawl, and an umbrella: With these items, Mrs. Joe is prepared for bad weather. Pattens were a sort of shoe-protector, described by the Dictionary of Daily Wants (1858-9) as "Articles made for the feet, to protect them from wet and damp. From their clumsiness, and the danger attending the wearing of them, they are now [1859, about two years before this part of Great Expectations was published] seldom worn, and are almost entirely superseded by the clog and galosh" (761). Though perhaps old-fashioned by 1859, the fact that Mrs. Joe carries pattens about with her in 1819 is stranger because of the mild weather in Rochester than because of the pattens themselves.

Sal volatile and ginger: When Camilla insists that "Raymond is a witness what ginger and sal volatile I am obliged to take in the night" (Ch. 11), she is referring to doses of popular restoratives. According to the OED, sal volatile is composed of ammonium carbonate; ginger, of course, is the same as the ginger we cook with today. The Dictionary of Daily Wants (1858-9) describes

SAL-VOLATILE. -- This is an excellent stimulant, and frequently employed in languor, faintings, hysteria, flatulent colic, and nervous debility, in doses of from half a teaspoonful to two teaspoonfuls; it may be given with the same quantity of spirit of lavender in a wineglass of water, which increases its beneficial effect. (879)

Ginger, according to the Dictionary of Daily Wants (1858-9), had several medicinal properties:

GINGER ... is an aromatic, stimulant, and stomachic, very useful in flatulence and spasms of the stomach and bowels, and in loss of appetite and dyspepsia, arising from debility or occurring in old and gouty subjects. It often relieves toothache, relaxation of the uvula, tender gums, and paralytic affections of the tongue. Made into a paste it forms a useful and simple headache plaster, which frequently gives relief when applied to the forehead or temples. It is also one of the most agreeable and wholesome spices, and is extensively used as a condiment and flavouring ingredient. In this character it is stimulating to the digestive organs, and is less hurtful than pepper; but, like all excitants, it should be used with moderation. (468)