|

NOTES ON ISSUE 12: GLOSSARY

PART 2 OF 3

Models of it [La Guillotine] were

worn on breasts from which the Cross was discarded, and it was bowed

down to and believed in where the Cross was denied.

This image – of the guillotine supplanting the cross – symbolizes the

secularization of France (previously a Catholic country) under the

Republic. This secularization – the acknowledgment of “no Religion but

Liberty” – sped the adoption of the Calendar of the “New Era” (the

abandonment of the calendar based on a Christian timeline), the

conversion of Notre Dame (the great Catholic cathedral of Paris) into a

“Temple of Reason,” the melting of church-bells into cannon, the

appropriation of mass-books to cartridge-papers, and so forth (Carlyle

693-4).

…it, and the ground it most polluted, were a rotten

red.

The ground “most polluted” by the guillotine was that of the Place de

la Révolution in Paris. Called, before the Revolution, the Place

de Louis XV, and now called the Place de la Concorde, it is situated

between the Champs-Élysées and the Jardin des Tuileries

(called the Jardin National during the Revolution). However, though

this was the chief location of the Parisian guillotine, the site of

execution was moved, at the height of the Terror, from place to place.

Carlyle gives this account of the shift:

Meanwhile will not the people of

the Place de la Révolution, the inhabitants along the Rue

Saint-Honoré as these continual Tumbrils pass, begin to look

gloomy? Republicans too have bowels. The Guillotine is shifted, then

again shifted; finally set up at the remote extremity of the

South-east; Suburbs Saint-Antoine and Saint-Marceau, it is to be hoped,

if they have bowels, have very tough ones. (731)

The guillotine did not remain in the eastern districts,

however, but was back in the Place de la Révolution

by the end of the Terror: Robespierre was beheaded there (Carlyle

743). Baedeker’s Paris and Its Environs (1878)

gives a descriptive and historical account of the plaza in which

the guillotine chiefly stood:

The

Place de la Concorde …, the most beautiful and extensive place in

Paris, and one of the finest in the world, covers an area 390 y[ards]

in length, by 235 y[ards] in width, bounded on the S[outh] by the

Seine, on the W[est] by the Champs Elysées, on the N[orth] by

the Rue de Rivoli, and on the E[ast] by the garden of the Tuileries….

The Place was completed in its present form [of 1878] in 1854…. In the

middle of the [18th century] the site … was waste ground. After the

Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle (18th Oct., 1748), which terminated the

Austrian War of Succession, Louis XV “graciously permitted” the mayor

and municipal authorities to erect a statue to him here. The work was

at once begun by the architect Gabriel,

and at length in 1763 an

equestrian statue in bronze by Bouchardon, with a pedestal

adorned by Pigalle with

figures emblematical of Strength, Wisdom,

Justice, and Peace, was erected here. The Place then received the name

of Place Louis XV….

The Place was at that period surrounded by deep ditches, but these were

filled up, and a balustrade substituted for them in 1852. On 30th May,

1770, during an exhibition of fireworks in honour of the marriage of

the Dauphin (afterwards Louis XVI) with the Archduchess Marie

Antoinette, such a panic was occasioned by the accidental discharge of

some rockets, that no fewer than 1200 persons were crushed to death,

or killed by being thrown into the ditches, and 2000 more severely

injured.

On 11th August, 1792, the day after the capture of the Tuileries, the

statue of the king was removed by order of the Legislative Assembly,

melted down, and converted into pieces of two sous. A terracotta figure

of the “Goddess of Liberty” was then placed on the pedestal, … while

the Place was named Place de la Révolution.

On 21st Jan., 1793, the guillotine began its bloody work here with the

execution of Louis XVI. On 17th July Charlotte Corday was beheaded; [in

late] October Brissot, chief of the Gironde, with twenty-one of his

adherents; on 16th Oct[ober] the ill-fated queen Marie Antoinette; on

14th Nov[ember] Phillipe Egalité, Duke of Orléans, father

of King Louis Philippe; [in] May, 1794, Madame Elisabeth, sister of

Louis XVI. [In] March, through the influence of Danton and

Robespierre, Hébert, the most determined opponent of all social

rule, together with his partizans, also terminated his career on the

scaffold here. The next victims were the adherents of Marat and the

Orleanists; then [in] April Danton himself and his party, among whom

was Camille Desmoulins; and [then] the atheists Chaumette and

Anacharsis Cloots, and the wives of Camille Desmoulins, Hébert,

and others. On 28th July 1794, Robespierre and his associates, his

brother, Dumas, St. Just, and other members of the “comité

de

salut public” met a retributive end here; next day the same fate

overtook 70 members of the Commune, whom Robespierre had

employed as his tools, and on 30th July twelve other members of the

same body….

Between 21st Jan., 1793, and 3rd May, 1795, upwards of 2800 persons

perished here by the guillotine. A proposal afterwards made to erect a

large fountain on the spot where the scaffold of Louis XVI had stood

was strenuously opposed by Chateaubriand, who aptly observed that all

the water in the world would not suffice to remove the blood-stains

which sullied the Place. (153-5)

It is chiefly this ground, which

“all the water in the world” could not wash of its

blood-stains, that Dickens describes as a “rotten red.”

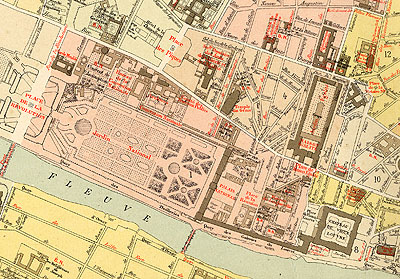

Click on

map for larger view

The Place de la Révolution

is visible on this portion of the Plan de la Ville de Paris,

Période Révolutionnaire, 1790-1794, at the

far left, above the Seine.

Twenty-two friends of high public mark, twenty-one living

and one dead, it had lopped the heads off, in one morning, in

as many minutes.

The “Twenty-two friends of high public mark” are

the members of the moderate Girondin party, defeated by the

Jacobin faction (of Danton, Robespierre, etc.) and guillotined

on October 31, 1793. Carlyle relates the circumstances, including

how Valazé, though already dead (having committed suicide),

was beheaded with his fellows, in a chapter called “The

Twenty-Two”:

The next are of a different

colour: our poor Arrested Girondin Deputies. What of them

could still be laid hold of; our Vergniaud, Brissot, Fauchet,

Valazé, Gensonné; the once flower of French

Patriotism, Twenty-two by the tale…. [T]he Sentence

on one and all of them is, Death with confiscation of goods….

[O]n the morrow morning all Paris is out; such a crowd as

no man had seen. The Death-carts, Valazé’s cold

corpse stretched among the yet living Twenty-one, roll along.

Bareheaded, hands bound; in their shirt-sleeves, coat flung

loosely round the neck; so fare the eloquent of France; bemurmured,

beshouted. To the shouts of Vive la République,

some of them keep answering with counter-shouts of Vive

la République. Others, as Brissot, sit sunk in

silence. At the foot of the scaffold they again strike up,

with appropriate variations, the Hymn of the Marseillese [a

patriotic song]. Such an act of music; conceive it well! The

yet Living chant there; the chorus so rapidly wearing weak!

Samson’s axe is rapid; one head per minute, or little

less. The chorus is wearing weak; the chorus is worn out; – farewell for evermore, ye Girondins.

Te-Deum Fauchet has become silent; Valazé’s dead

head is lopped: the sickle of the Guillotine has reaped the

Girondins all away. (671-3)

So much more wicked and

distracted had the Revolution grown in that December month, that the

rivers of the South were encumbered with the bodies of the violently

drowned by night, and prisoners were shot in lines and squares under

the southern wintry sun.

Though Dickens’ reference to the “rivers of the South encumbered with

bodies” is often glossed as a reference to the Republican (Jacobin)

suppression of Lyons, a Girondin-supporting region of southern France

(Sanders 145, Maxwell 472), Lyons was suppressed in October of 1793 –

not

December. There were bodies in the southern rivers as the

Republic put down Lyons – Carlyle writes that “Revolutionary Tribunal

[t]here, and Military Commission, guillotining, fusillading, do what

they can: the kennels of the Place de Terreaux run red; mangled corpses

roll down the Rhone” (686-8). However, Dickens seems to be referring to

another set of bodies – those drowned in the first “Noyades”

of December 1793 at Nantes:

One

begins to be sick of “death vomited in great floods.” Nevertheless,

hearest thou not, O Reader (for the sound reaches through centuries),

in the dead December and January nights, over Nantes Town, – confused

noises, as of musketry and tumult, as of rage and lamentation; mingling

with the everlasting moan of the Loire waters there? Nantes Town is

sunk in sleep; but Représentant Carrier is not

sleeping, the wool-capped Company of Marat is not sleeping. Why unmoors

that flatbottomed craft, that gabarre; about eleven at night;

with Ninety Priests under hatches? They are going to Belle Isle? In the

middle of the Loire stream, on signal given, the gabarre is scuttled;

she sinks with all her cargo. “Sentence of Deportation,” writes

Carrier, “was executed vertically.”

The Ninety Priests, with their gabarre-coffin, lie deep! It is the

first of the Noyades, what we may call Drownages, of Carrier; which have

become famous for ever.

Guillotining there was at Nantes, till the Headsman sank worn out: then

fusillading “in the Plain of Saint-Mauve”; little children fusilladed,

and women with children at the breast; children and women, by the

hundred and twenty; and by the five hundred, so hot is La

Vendée: till the very Jacobins grew sick, and all but the

Company of Marat cried, Hold! Wherefore now we have got Noyading; and

on the 24th night of Frostarious year 2, which is 14th of

December, 1793, we have a second Noyade; consisting of “a Hundred and

Thirty-eight persons.”

Or why waste a gabarre, sinking it with them? Fling them out; fling

them out, with their hands tied…. [w]omen and men are tied together,

feet and feet, hands and hands; and flung in: this they call Mariage

Républicain, Republican Marriage. (Carlyle 691-2)

These “Noyades”

seem to be the December

drownings to which Dickens refers, though he may well be conflating the

atrocities of Nantes with those of Lyons. Nantes, it will be remarked,

is not properly in the South of France, and thus does not fall under

a “southern wintry sun”; however, like Lyons, Nantes is on a river (the

Loire), it was

(again, like Lyon) in revolt against the Republic, and it is, if not in

the South of France, at any rate

south of Paris. Furthermore, Dickens’ geographical conflation follows

Carlyle’s own grouping of events. The opening paragraph of the chapter

in which Carlyle discusses the suppression of Lyons and Nantes runs as

follows:

The

suspect may well tremble, but how much more the open rebels; the

Girondin Cities of the South! Revolutionary Army is gone forth, under

Ronsin the Playwright; six thousand strong, … and has portable

guillotines. Representative Carrier has got to Nantes, by the edge of

blazing La Vendée, which Rossignol has literally set on fire:

Carrier will try what captives you make; what accomplices they have,

Royalists or Girondin: his guillotine goes always, va toujours; and his wool-capped

“Company of Marat.” (685)

Carlyle, like Dickens after him, groups

Nantes with the “Girondin Cities of the South.”

The billet fell as he spoke, and he threw it into a

basket. “I call myself the Samson of the firewood guillotine.”

A “billet,” in this sense, is “[a] thick piece of wood cut to a

suitable length for fuel” (OED); and the woodman calls himself

the “Samson of the firewood guillotine” because he – like the public

executioner – cuts or shaves. In French, of course, a “billet” is also

a ticket, note or letter. The alternate meanings of the word may

suggest

that this Samson does double duty – first as a woodman, and second as

an informer.

On a lightly-snowing afternoon she arrived at the

usual corner. It was a day of some wild rejoicing, and a festival.

This winter day of “wild rejoicing” is probably based upon the

festivities of November 10, 1793 (or, more generally, November and

December 1793), when – following the widespread renunciation by priests

and curates of the Catholic religion (in favor of the “Fraternal

embrace” and “no Religion but Liberty” [Carlyle 694]) – a procession of

citizens, having despoiled the churches, jubilantly visited the

National Convention. Carlyle describes this parade, and the events

leading up to it, as follows:

From

afar and near, all through November into December, till the work is

accomplished, come Letters of renegation, come Curates who “are

learning to be Carpenters,” Curates with their new-wedded Nuns: has not

the day of Reason dawned, very swiftly, and become noon?… This ... is

what the streets of Paris saw:

“Most of these people were still drunk, with the brandy they had

swallowed out of chalices; – eating mackerel on the patenas! Mounted on

Asses, which were housed with Priests’ cloaks, they reined them with

Priests’ stoles; they held clutched with the same hand communion-cup

and sacred wafer. They stopped at the doors of Dram-shops; held out

ciboriums: and the landlord, stoop in hand, had to fill them thrice.

Next came Mules high-laden with crosses, chandeliers, censers,

holy-water vessels, hyssops; – recalling to mind the Priests of Cybele,

whose panniers, filled with the instruments of their worship, served at

once as storehouse, sacristy, and temple. In such equipage did

these profaners advance towards the Convention. They enter there, in an

immense train, ranged in two rows; all masked like mummers in fantastic

sacerdotal vestments; bearing on hand-barrows their heaped plunder, –

ciboriums, suns, candelabras, plates of gold and sliver.” [Carlyle’s

source here is Mercier on the “Séance of 10 Novembre.”]

The Address we do not give; for indeed it was in strophes, sung vivâ voce, with all the

parts; – Danton glooming considerably, in his place; and demanding that

there be prose and decency in future. Nevertheless the captors of such spolia opima crave, not untouched

with liquor, permission to dance the Carmagnole also on the spot:

whereto an exhilarated Convention cannot but accede. Nay “several

Members,” continues the exaggerative Mercier, who was not there to

witness…, “several Members, quitting their curule chairs, took the hand

of girls flaunting in Priests’ vestures, and danced the Carmagnole

along with them.” Such Old-Hallowtide have they, in this year, once

named of Grace 1793. (694-6)

Though probably based on the

sacrilegious festivities of November 10, the day of “wild rejoicing” to

which Dickens refers could be any day in November or December 1793 –

the interval in which Catholicism was widely denounced (even by its

most reverend members) in favor of “Liberty” and “Reason.” The

disapprobation implied in Carlyle’s reference to the year “once

named of Grace 1793” (emphasis added) is reflected in Dickens’

representation of the

festivities as sinister and disturbing. Under the New Calendar of the

New Era of the French Republic, the Christian holidays were of course

thrown out, replaced by occasional secularized holidays. Indeed, having

divided the

year into twelve months of thirty days each, the New Calendar had five

days left over. These five days became a festival period, to be added

to the end of “Fructidor” (August in the “old” calendar). Carlyle

explains this part of the

calendar as follows:

Four equal

Seasons, Twelve equal Months of Thirty days each; this makes

three hundred and sixty days; and five odd days remain to

be disposed of. The five odd days we will make Festivals,

and name the five Sansculottides, or Days without

Breeches [the revolutionaries were called “sansculottes”

because they did not wear knee-breeches like the aristocracy].

Festival of Genius; Festival of Labour; of Actions; of Rewards;

of Opinion; these are the five Sansculottides. Whereby the

great Circle, or Year, is made complete: solely every fourth

year, whilom called Leap-year, we introduce a sixth Sansculottide:

and name it Festival of the Revolution. (660)

|