|

NOTES ON ISSUE 2: GLOSSARY

PART 1 OF 3

Printable View

A large cask of wine had been

dropped and broken, in the street…, the hoops had burst, and it lay on

the stones just outside the door of the wine-shop, shattered like a

walnut-shell.

A cask is a barrel “formed of curved staves bound together by hoops,

with flat ends or ‘heads’” (Oxford

English Dictionary), and like a walnut because it is round and

wooden. The Dictionary of Daily Wants

(1859) describes a cask as follows, and gives us this illustration of a

cask in a cask-stand:

CASK. – A vessel of capacity for

containing beer, wine, and other liquids. The care and management of

casks is an important affair in a large establishment. It is found that

they last longest when stored either in a dry situation, or in one

uniformly very moist. Continual variations from one atmosphere to

another speedily rot casks. As soon as casks are emptied they should be

bunged down quite air-tight, with as much care as if they were full, by

which means they will be preserved both sweet and sound. Should any of

the hoops become loose, they should be immediately driven up tight,

which will at once prevent the liability of their being lost or

misplaced, as well as the casks becoming foul or musty from the

admission of air. For this purpose those out of use should be

occasionally examined. To sweeten casks when musty, it is best to

unhead them and wash them with quick-lime, or they may be washed with

oil of vitriol diluted with an equal weight of water. When casks are

very foul and resist these remedies they should be charred; a simple

and effectual method of performing this, is to wash the dry casks out

with the strongest oil of vitriol. In all cases the greatest care must

be taken to scald or soak, and well rinse out the casks after

subjecting them to this purifying process. (248)

The rough, irregular stones of the

street, pointing every way, and designed, one might have thought,

expressly to lame all living creatures that approached them, had dammed

it into little pools.

The streets were first paved in Paris beginning in 1450 (Baillie and

Salmon 119), but even-surfaced modern paving like macadam was not

invented until the 1820s (OED).

In 1775 (the year in which this portion of A Tale of Two Cities is set), as in

Dickens’ time, roads were paved with stones. A description in the Dictionary of Daily Wants (1859)

offers some idea of the difficulty of laying smooth roads:

PAVING. – In preparing for laying

down pavements, the first thing to be attended to is the foundation.

This must be made of strong and uniform materials, well rammed

together, and accurately formed, to correspond with the figure of the

superincumbent pavement. The kinds of stone used in paving are chiefly

granite, whinstone or trap, Guernsey or other pebbles, or water-worn

granite or trapstones. The size of the stones used in road paving is

commonly from five to seven inches long, from four to six inches broad,

and from six to eight inches deep. In laying down stones, each stone

should lean broadly and fairly on its base; and the whole should be

rammed repeatedly to make the joints close; the upper and lower sides

of the stones should be as near each other as possible, but they should

not touch each other laterally except near the top and bottom, leaving

a hollow in the middle of their depth to receive gravel, which will

serve to hold them together. This method of paving may be easily

executed by common workmen, who may throw in gravel between the stones

as they are laid down. It will be useful to cover newly-laid pavement

and gravel, which will preserve the fresh pavement for some time from

the irregular pressure of wheels till the whole is consolidated. The

stones should be of equal hardness, or the soft ones will be worn down

into hollows. In every species of paving, no stones should be left

higher or lower than the rest; for a wheel descending from a higher

stone will, by repeated blows, sink or break the lower stone upon which

it falls. (761)

Without proper maintenance, the paved

roads of districts like the one described by Dickens would quickly

become irregular and would be likely enough, as he says, to “lame all

living creatures.”

…the sodden and lee-dyed pieces of the cask…

The “lee” is “[t]he sediment deposited in the containing vessel from

wine and some other liquids” (OED).

The word is often used figuratively (in phrases like “to the lees”) to

mean “to the very end,” because the sediment of wine, being heavier,

tends to remain at the bottom of the cask or bottle. Casks would become

“lee-dyed” from this residue.

There was no drainage to carry off the wine…

Paris sanitation was more or less non-existent until the 14th

century, when King Phillipe Augustus began to take steps to

sanitize the city. One of his major contributions was to have

the roads paved, in order to reduce the smell of waste thrown

into the street (which became malodorous as it was assimilated

with the mud). In response to plagues in the 16th century, cesspools

for the collection of wastes were mandated under each city dwelling

– but water-tightness was not required until the 19th.

In the 18th century, cesspools and

kennels – drains in the middle of street – were the primary means of

dealing with wastes in Paris. However, the most usual method for

disposing of garbage was “tout-a-la-rue” – “all in the street.” The

practice of chucking household garbage out the window had existed since

the period of the earliest attempts at sanitation in Paris, but

persisted into the 19th century, and was certainly the mode at the

period in which A Tale of Two Cities

is set: In 1780, an ordinance “once again forbade people from throwing

water, urine, feces or household garbage out the window” (Krupa, Paris: Urban Sanitation), and

Dickens himself describes how “…the room or rooms within every door

that opened on the general staircase [in the Saint-Antoine dwelling]

left its own heap of refuse on its own landing, besides flinging other

refuse from its own windows.” Thus, not only would there be “no

drainage to carry off the wine” spilled in the Paris street Dickens

describes, but drinking wine that had fallen on the paving stones could

seriously compromise one’s health.

The wine was red wine, and had stained the ground of the

narrow street in the suburb of Saint Antoine, in Paris, where it was

spilled.

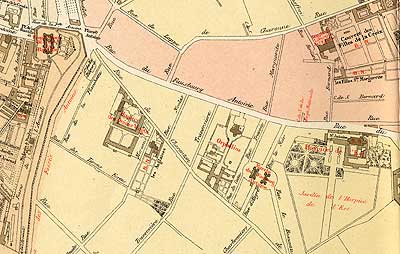

The Parisian suburb of Saint Antoine, located east of the (then-standing)

Bastille, and oriented around the Faubourg Saint Antoine, became

part of Paris in 1702 (Maxwell 446). Now part of the Eleventh

Arrondissement [there are twenty arrondissements – postal

districts – in Paris (Baillie and Salmon 54)], it was,

in the 18th century and Dickens’ own time, a poor manufacturing

district; it is still, as contemporary guidebooks point out,

“working class … and a little scruffy” (Baillie

and Salmon 55).

Ever since the French Revolution, Saint

Antoine has been known for its revolutionary fervor, having played a

prominent part in the uprisings of 1789, 1841, and 1851 (Sanders 43-4).

The district was named after the Abbaye de Saint-Antoine-des-Champs, an

abbey built at the end of the 12th century on the site of a chapel

dedicated to Saint Anthony (Saint Antoine is the French version of Saint Anthony) (Berman 121-50). The Abbey is still visible on maps of Paris

up to 1789, but – with the confiscation of ecclesiastical property

during the Revolution – it became a Hospice.

The Abbaye St. Antoine, afterwards the Hospice de l’Est, is visible on

the Plan de la Ville de Paris en 1789

and the Plan de la Ville de Paris, Période Révolutionnaire, 1790-1794.

The portions of these maps given below – mapping the area between the

Place de la Bastille and the Abbaye/Hospice, in eastern Paris – show

the abbey/hospice at the far right.

Click on map for larger view

Click

on map for larger view

…many naked feet, and many wooden

shoes…

The wooden shoes of the French workers were called “sabots.” Carlyle

frequently refers to the “sabots” of the French peasants in The French Revolution, and the OED describes them as “wooden

shoe[s] made of a single piece of wood shaped and hollowed out to fit

the foot” or “[a] kind of shoe having a thick wooden sole and ‘uppers’

of coarse leather.” It is interesting to note that the word “sabotage”

– which seems to have come into English usage in the 20th century –

derives from the rebellious use to which the laboring classes put their

sabots. The OED gives the

following derivation from the French word “saboter” – “to make a noise

with sabots, to perform or execute badly, e.g. to ‘murder’ (a piece of

music), to destroy willfully (tools, machinery, etc.).” Sabots, in

short, have become symbolic of working-class rebellion and revolution.

...stave of the cask...

Staves are “narrow, shaped pieces of wood which, when placed together

side by side and hooped, collectively form the side of a cask, tub or

similar vessel” (OED).

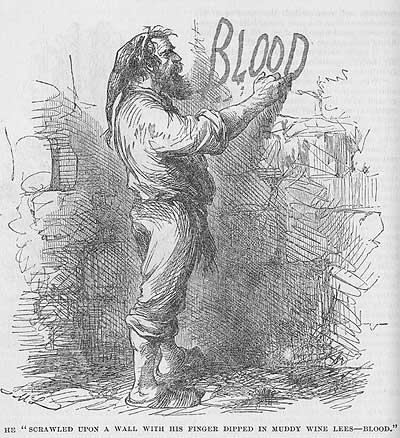

…scrawled upon the wall with his finger dipped in muddy

wine lees – BLOOD.

Since this portion of the novel occurs

in France, the word scrawled upon the wall – though by

novelistic convention given by Dickens in English (“BLOOD”)

– would be the word SANG (French for “blood”).

The illustration of this scene in the American edition of 1859

(Peterson’s Uniform Edition of A Tale of Two Cities) extends the convention

to the visual register as well, and has the Frenchman writing

in English upon the wall of Saint Antoine.

And

now that the cloud settled on Saint Antoine, which a momentary gleam

had driven from his sacred countenance, the darkness of it was heavy –

cold, dirt, ignorance, want…

Dickens’ personification of Saint Antoine – his

tendency to refer to the district as though it were a single

person – is continued throughout the novel. The “sacred

countenance” of the Saint Antoine described here is of

course the metaphorical “countenance” or “face”

of the neighborhood – its streets, its denizens, and so

forth. However, the original “sacred countenance”

of Saint Antoine belonged to Saint Anthony, for whom the district

was – indirectly – named.

The Saint Antoine district was named

after the Abbaye de Saint-Antoine-des-Champs (the “Abbey of St. Anthony

of the Fields”), which was founded in the last decade of the 12th

century on the site of a chapel already dedicated to Saint Anthony

(Berman 121-56). Though there have been a number of saints named

Anthony, the saint to whom the abbey and its predecessor were dedicated

is probably the Saint Anthony known as the “patriarch of monks,” or

“Saint Anthony of the Desert,” born in Egypt in 251 A.D. According to

the notation on his Saint’s Day in the Book of Days (1864), he is “one of

the most notable saints in the Romish [i.e. Catholic] calendar” (124,

vol. 1) and

The Temptations of St. Anthony

have, through St. Athanasius’s memoir, become of the most familiar of

European ideas. Scores of artists from Salvator Rosa [a famous

picturesque painter of the 17th century] downwards, have exerted their

talents in depicting these mystic occurrences. Satan, we are informed,

first tried, by bemudding his [St. Anthony’s] thoughts, to divert him

from the design of becoming a monk. Then he appeared to him in the form

successively of a handsome woman and a black boy, but without in the

least disturbing him. Angry at the defeat, Satan and a multitude of

attendant fiends fell upon him during the night, and he was found in

his cell in the morning lying to all appearance dead. On another

occasion, they [Satan and his fiends] expressed their rage by making

such a dreadful noise that the walls of his cell shook. “They

transformed themselves into shapes of all sorts of beasts, lions,

bears, leopards [etc.] …; so that Anthony was tortured and mangled by

them so grievously that his bodily pain was greater than before.” But …

he taunted them, and the devils gnashed their teeth. This continued

till the roof of his cell opened, a beam of light shot down, the devils

became speechless. Anthony’s pain ceased, and the roof closed again….

(124)

Hunger was the inscription on the

baker’s shelves, written in every small loaf of his scanty stock of bad

bread; at the sausage-shop, in every dead-dog preparation that was

offered for sale. Hunger rattled its dry bones among the roasting

chestnuts in the turning cylinder; Hunger was shred into atomies in

every farthing porringer of husky chips of potato, fried with some

reluctant drops of oil.

Throughout A Tale of Two Cities,

hunger and taxation are represented as primary causes of revolutionary

feeling among the poor, just as Dickens’ chief historical source –

Carlyle’s French Revolution –

gives similar attention to the impact of bad harvests, famine, and

disproportionate taxation. The emphasis on bread as the foodstuff

demanded is partly a figure of speech for food of all kinds, yet is

also partly literal: Bread provided about half the calories of an adult

diet in the 18th century (Maxwell 447).

Potato “chips” (the precursor of the modern French fry – which the

English still call chips) were, at this period, still a uniquely French

food. As Sanders notes in his Companion

to A Tale of Two Cities, “fish and chips” was apparently not yet

part of the English diet when Dickens was writing A Tale of Two Cities. Though fried

fish was sold in the streets of London, fish and chips was not yet

advertised (44).

Chestnuts, planted as ornamental trees in the public gardens of Paris,

were as common in the Paris of Dickens’ time as they are in our own;

and though most of the Parisian chestnuts were planted when the gardens

were refurbished after the French Revolution (Baillie and Salmon 91),

the plants have always been congenial to the city. The Dictionary of Daily Wants (1859)

gives the following instructions for roasting chestnuts:

CHESTNUTS ROASTED. – The best way

of preparing these is to roast them in a coffee-roaster, after having

first boiled them from seven to ten minutes, and wiped them dry. They

should not be allowed to cool, and will require but ten or twelve

minutes roasting. They may, when more convenient, be finished over the

fire as usual, or in a Dutch or common oven; but in all cases, the

previous boiling will be found an improvement. Never omit to cut the

rind of each nut slightly before it is cooked. Serve the chestnuts in a

napkin, very hot, and send salt to the table with them. (276)

The Dictionary’s

illustration of a coffee-roaster (which it recommends for the

roasting of both coffee and chestnuts) gives us some idea of

what Dickens’ “turning cylinder” would have

looked like. This kind of machine contained a charcoal-burning

fire for roasting the chestnuts or coffee beans.

A farthing (as in “a farthing porringer

of husky chips of potato”) was an English coin worth a quarter of a

penny (OED); and a porringer

is a rough bowl usually used to contain liquid foods – soup, porridge,

etc. (OED). A farthing

porringer suggests a scanty, simple meal.

The kennel, to make

amends, ran down the middle of the street – when it ran at all: which

was only after heavy rains, and then it ran, by many eccentric fits,

into the houses.

Though cesspools under buildings constituted the chief Parisian

“sewers” from the 16th century onward, reducing the amount of refuse in

the streets, the continued waste-disposal practice of “tout-a-la-rue”

(“all in the street,” against which legislation was still being passed

in the 1780s), more or less necessitated a primitive system of kennels

– surface drains or gutters (OED)

– running down the middle of the street. The very poorest of Paris

occasionally made a living by transporting pedestrians across the

kennels on boards laid down for the purpose (Krupa, Paris: Urban Sanitation).

Across the streets, at wide intervals, one clumsy lamp

was slung by a rope and pulley; at night, when the lamplighter had let

these down, and lighted, and hoisted them up again, a feeble grove of

dim wicks swung in a sickly manner overhead…

In the 18th century, Paris was lit – when lit at all – with oil lamps

(gas lighting was not introduced until 1819 [Hobsbawm 298]). Until the

reign of Louis XVI (the king during the period in which this part of A Tale of Two Cities is set), Paris

was lighted for only nine months of the year, and not lighted even

during these months when there was a moon. The city lamps were as

Dickens describes – “lamps suspended from ropes hung across the street,

which, though aided by reflectors, and kept well cleaned, … served for

little else than to make darkness visible” (Galignani’s New Paris Guide [1842],

qtd. in Sanders 45).

|