|

NOTES ON ISSUE 2: GLOSSARY

PART 2 OF 3

…hauling up men by those ropes and

pulleys, to flare upon the darkness of their condition.

The practice of hanging offenders from the Parisian street-lanterns

becomes, in A Tale of Two

Cities, as in Dickens’ chief historical source

(Carlyle’s French Revolution), emblematic of patriotic

retribution. In The French

Revolution, the practice is inaugurated in a chapter

titled “The Lanterne,” in which the people, after

taking the Bastille, hang certain officials from the lanterns

near the Hôtel de Ville. “To the lantern!”

or simply “Lanterne!”

always implies, in Carlyle, imminent execution.

The Paris lanterns, and especially their projecting

lamp-irons, were apparently of convenient shape and stature

for use as makeshift gallows. Mercier (whose Tableau de Paris [1771-88] was one of Dickens’

French sources) notes, in an account of “Street Lighting”

(“Réverbères”), that the

oil-lamps of Paris were “badly hung; they made, in Milton’s

words, darkness itself visible. They should be fixed close to

the wall, not swung out above the street on great brackets”

(43). It is perhaps this distance of the lantern from the wall,

and the length of the bracket from which the oil-lamp was suspended,

which suggested the more grisly use to which the fixtures could

be put.

“What now? Are you a subject for the mad-hospital?”

“Mad-hospitals” in France dated from the mid-17th

century, but were not like modern asylums for the mentally ill.

Instead, they were more like prisons, outfitted with cells and

dungeons, and they contained not only the “mad,”

but also the poor, the indigent, the unemployed, and the criminal.

Michel Foucault notes that, after the establishment of these

hospitals, “one out of every hundred inhabitants of the

city of Paris found themselves confined there” (124);

in fact, he associates confinement in mad-hospitals with the

confinement resulting from a lettre de cachet, and suggests that madness

was in fact generated by confinement to hospitals – not

cured by it. Thus, when Defarge asks the man who writes “BLOOD”

on the wall in the Saint Antoine district whether he is a subject

for the mad-hospital, this may be a critique of the man’s

sanity; on the other hand, it may – in light of the nature

of such institutions at the time – be merely a critique

of his idleness.

The Hôpital Général, established

by royal edict in 1656, initiated what Foucault calls the “Great

Confinement,” intended to heal the sick, but also to prevent

“mendicancy and idleness as the source of all disorders”

(Foucault 124-9). Dickens, sensitive to social injustices and

particularly to the institution of social confinement (a visit

to Newgate Prison is recorded in Sketches

by Boz, and a visit to prisoners in solitary confinement

in a Philadelphia prison is described in

American Notes) would probably have been well aware of

the nature of French madhouses (and similar English ones, like

Bedlam) in the 18th century. Further, he may have read Mercier’s

report of Bicêtre in the Tableau

de Paris (1781-88), a collection of sketches on which

he drew for details of pre-revolutionary Paris:

Debtors are incarcerated here [in Bicêtre],

beggars, and madmen, together with all the viler criminals,

huddled pell-mell. There are others, too; epileptics, imbeciles,

old men, paupers and cripples, who, not being criminals, are

known by the generic title of “good poor”; to my

mind they should find refuge elsewhere, apart from the rogues

their neighbors. (160)

Mercier’s description of the appalling

conditions in Bicêtre – as many as six sick men

to a bed, a general lack of ventilation and drainage (to the

extent that one prisoner feigned death three times just to be

carried upstairs to purer air, and wasn’t believed when

he finally did die) – tends to confirm Foucault’s

argument that asylums frequently created the illness and insanity

they were meant to cure.

Her knitting was before her, but she had laid it down to

pick her teeth with a toothpick.

As Richard Maxwell points out in his edition of A Tale of Two Cities, Dickens revised his

original portrait of Madame Defarge to agree with the image

of the citoyennes tricoteuses

– the “knitting citizens” (female) of the

Revolution, “notorious for their regular attendance at

public executions” (448). In Dickens’ original conception

(found in the manuscript version of A Tale), Madame Defarge was addicted to needlework

instead of knitting.

“What the devil do you do in that galley there?”

said Monsieur Defarge to himself.

This apostrophe of Monsieur Defarge’s is usually used

as an example of Dickens’ attempt to represent French

linguistic constructions in English. Sanders, in his Companion

to A Tale of Two Cities, glosses “What the devil

do you do in that galley there?” as the idiomatic “equivalent

of the French ‘Que faites-vous dans cette galère?’

– ‘What are you doing in this mess?’”

(47). Monsieur Defarge’s “what … do you do”

is meant to reflect the French use of a present tense verb.

In English, we would choose between the present and the present

progressive. (“Que faites-vous?”

is an interrogative conjugation which may be translated either

“What are you doing?” or “What do you do?”

according to the context of the phrase.)

…and fell into discourse with the triumvirate of customers

who were drinking at the counter.

Here, “triumvirate” is used mainly in the generic

sense of a threesome; yet the word – adapted from the

Latin and originally referring, in Roman history, to “[t]he

position, office, or function of the triumviri …, an association

of three magistrates for joint administration” or “[b]y

extension: any association of three joint rulers or powers”

(OED) – suggests political collusion.

It may also faintly foreshadow the neo-classical allegiances

of revolutionary Paris, when “the republican spirit of

the Parisians revived the classical coiffure of Rome, and a

‘tête à la Brutus’” (Planché

403-4) demonstrated an aesthetic and political nostalgia for

antiquity.

“How goes it, Jacques?”

The fact that the members of the “triumvirate” with

whom Monsieur Defarge confers address one another as “Jacques”

not only supports the impression of their collusion, but invokes

the revolutionary overtones of the “Jacquerie”

– a name originally used as a general term for the French

peasantry (from the moniker “Jacques

Bonhomme” – roughly “Goodman James”

in English), but particularly applied to the individuals involved

in a 14th-century peasant rebellion (1357-8) in Northern France

(Sanders 47). This rebellion might be said, as a revolt of the

French poor against the aristocracy, to prefigure the Revolution

of 1789. Indeed, it not only contributes to Dickens’ revolutionary

vocabulary (his use of the term “Jacques”), but

to the geography of his revolutionary novel: The 14th-century

revolt of the Jacquerie was initiated in the area around

the town of Beauvais – the birthplace of Lucie’s

father, Doctor Manette, in A

Tale of Two Cities (Sanders 47).

…and nothing within range, nearer or lower than the

summits of the two great towers of Notre-Dame had any promise

on it of healthy life or wholesome aspirations.

The cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris, like St. Paul’s

cathedral in London, stands on ground which has had religious

significance since the period of Roman settlement. One 19th-century

guidebook gives the following account of its construction and

the religious buildings that preceded it on the spot:

Notre Dame … was begun in the year

1163 by Maurice de Sully, the sixty-second bishop of Paris.

Pope Alexander III laid the foundation-stone. Two churches had

stood previously upon the same ground …, one dedicated

to St. Etienne and the other to La Vierge Marie [the Virgin

Mary]. During … excavations [later] made … under

the choir of Notre Dame, stones were discovered showing that

the Parisian sailors had upon this spot erected an altar to

Jupiter, in the reign of Tiberius Caesar. In the 6th century

was dedicated the church to St. Etienne, and in the following

century, that to the Virgin…. (Dickens’s

Dictionary of Paris 165-7)

The religious significance of the location

of Notre Dame – from antiquity onward – contributes

to its status as a spiritual center for the city of Paris. Indeed,

Tronchet’s Picture of Paris (c. 1818) calls Notre Dame

“the mother church of France,” and Dickens frequently

uses it (though partly no doubt because of its fame even among

English readers) as a point of geographical reference in A Tale of Two Cities. Notre Dame stands on

the east side of the Ile de la Cité – one of the

Parisian islands in the Seine – and is less than a mile

from the Saint Antoine district (measured from the Place de

la Bastille as the crow flies). Nevertheless, the “summits

of the two great towers” of Notre Dame are probably more

of a symbolic than a literally visible landmark in A

Tale of Two Cities. At the beginning of the 19th century,

Notre Dame was described as follows:

[It is] so surrounded with houses that there

is no spot from which it may be seen with advantage. It is a

Gothic edifice, built in the form of a cross, and remarkable

for the lightness of its structure. But its two large square

towers, in giving a stateliness, give also a heaviness to the

building. (Tronchet 227)

The two great towers, which were apparently

originally intended to have spires, never received them. One

19th-century guidebook warns English tourists that “Until

our eye has got accustomed to the spireless towers they may

appear stumpy” (Dickens’s Dictionary of Paris

167); and Baedeker’s Paris and Its Environs (1878)

remarks that “The general effect, though not unimposing,

is hardly commensurate with the renown of the edifice. This

is owing partly to structural defects, partly to the lowness

of its situation, and partly to the absence of spires”

(212).

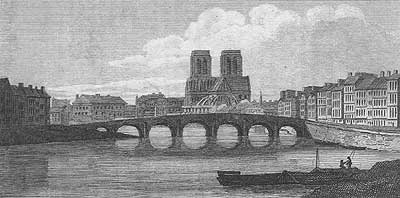

This engraving of Notre Dame, included in

Tronchet’s Picture of Paris (c. 1818), shows the

cathedral with the river in the foreground, from the east. The

perspective from Saint Antoine would be from the northeast –

and probably impeded.

Click

on map for larger view

This portion of the Plan de la Ville de Paris en 1789 shows Notre Dame relative to Saint

Antoine (the Bastille is visible at the far right).

“Why! Because he has lived so long, locked up, that

he would be frightened – rave – tear himself to

pieces – die – come to I know not what harm –

if his door was left open.”

In his account of the liberated behavior of Doctor Manette,

Dickens seems to follow French accounts of the experience of

actual prisoners of the Bastille. One of Dickens’ sources

for many of the Parisian elements of A

Tale of Two Cities was Mercier’s Tableau

de Paris (1781-88); and the character of Doctor Manette

is probably partly based on a figure in an “Anecdote”

in Mercier’s Tableau. In both the “Anecdote”

and A Tale of Two Cities,

the prisoner is released from the Bastille during the reign

of Louis XVI; in both, he finds his release unendurable; and

in both, he goes to live with an old servant. The “Anecdote”

is excerpted below:

When Louis XVI came to the throne, new and

humanitarian ministers performed an act of justice and clemency,

in inspecting the registers of the Bastille and freeing many

prisoners.

Among them was an old man who, for forty-seven years, groaned,

detained between four thick and cold walls…. [Then one

day the] lower door of his tomb turns on its frightening hinges,

opens, not just halfway, as is its custom, and an unknown voice

says to him that he can come out.

He thinks he is dreaming. He hesitates, he rises, he makes his

way with a trembling step, frightened of the huge space through

which he moves. The stairs of the prison, the hall, the court,

all appear enormous to him, almost without end. He stops as

though confused and lost; his eyes have difficulty tolerating

the full light of day; he looks at the sky as at an object utterly

new; he stares, he cannot cry. He is astounded by his freedom

to move from place to place; his legs, despite his efforts,

remain frozen as his tongue. He finally passes through the formidable

gate.

When he feels himself carried away in the vehicle which will

return him to his ancient habitation, he gives articulate cries;

he cannot tolerate the extraordinary movement; he must get out.

Conducted by a charitable arm, he asks for the street where

he once lodged. He arrives; his house is no longer there; a

public building has replaced it. He recognizes neither the quarter

nor the city nor the objects which he once knew. The dwellings

of his neighbors, imprinted on his memory, have taken new forms.

In vain his looks interrogate those around him; he does not

see a single face of which he has the faintest memory.

Terrified, he stops and gives a deep sigh. This city, so beautifully

peopled with living beings, it is for him a necropolis; no one

knows him; he knows no one; he weeps and longs for his cachot [dungeon cell].

At the name of the Bastille, which he invokes and claims for

himself as an asylum, at the view of his clothing, which speaks

of another era, a crowd surrounds him. Curiosity and pity press

in upon him; the oldest question him and have no idea of the

deeds which he recalls. By chance they bring him an old servant,

porter for a long time, trembling in the knees, who, confined

in his lodge for fifteen years, has scarcely enough strength

to pull the rope for the door.

He does not recognize the master he once served; but informs

him that his wife died thirty years ago, of sorrow and misery;

that his children have departed for unknown lands; that all

his friends are no more. The indifference with which this tale

is told shows that it speaks of events long ago, almost effaced….

Crushed by grief, he [the released prisoner] goes to find the

Minister whose generous compassion has made him a present of

that liberty which so much weighs upon him. He bows and says:

Let me be taken back to the prison from which you have drawn

me…. The minister’s heart grows tender. The unfortunate

one is given as a companion the old porter who can speak to

him still of his wife and children…. (qtd. in and translated

by Maxwell 416-7)

Doctor Manette’s response to liberation

is similar to the old man’s in Mercier’s “Anecdote.”

Though he was (as we find out later) imprisoned in the Bastille

for about 18 years instead of 47, and though his servant (Defarge)

is much younger, hailer and heartier than the old man’s,

the stories are obviously similar.

…unglazed, and closing up the middle in two pieces,

like any other door of French construction.

An “unglazed” window is simply one without glass

(OED); doors of “French construction”

are even now called “French doors” or “French

windows” (OED) and are readily recognizable –

instead of sliding up and down within a frame, or opening from

one side, a French window is “a long window opening like

a folding-door, and serving for exit and entrance” (OED).

|